Volt was the only squirrel El Camino College’s humans ever named.

On Nov. 21, 1997, ECC classes were canceled due to a power outage.

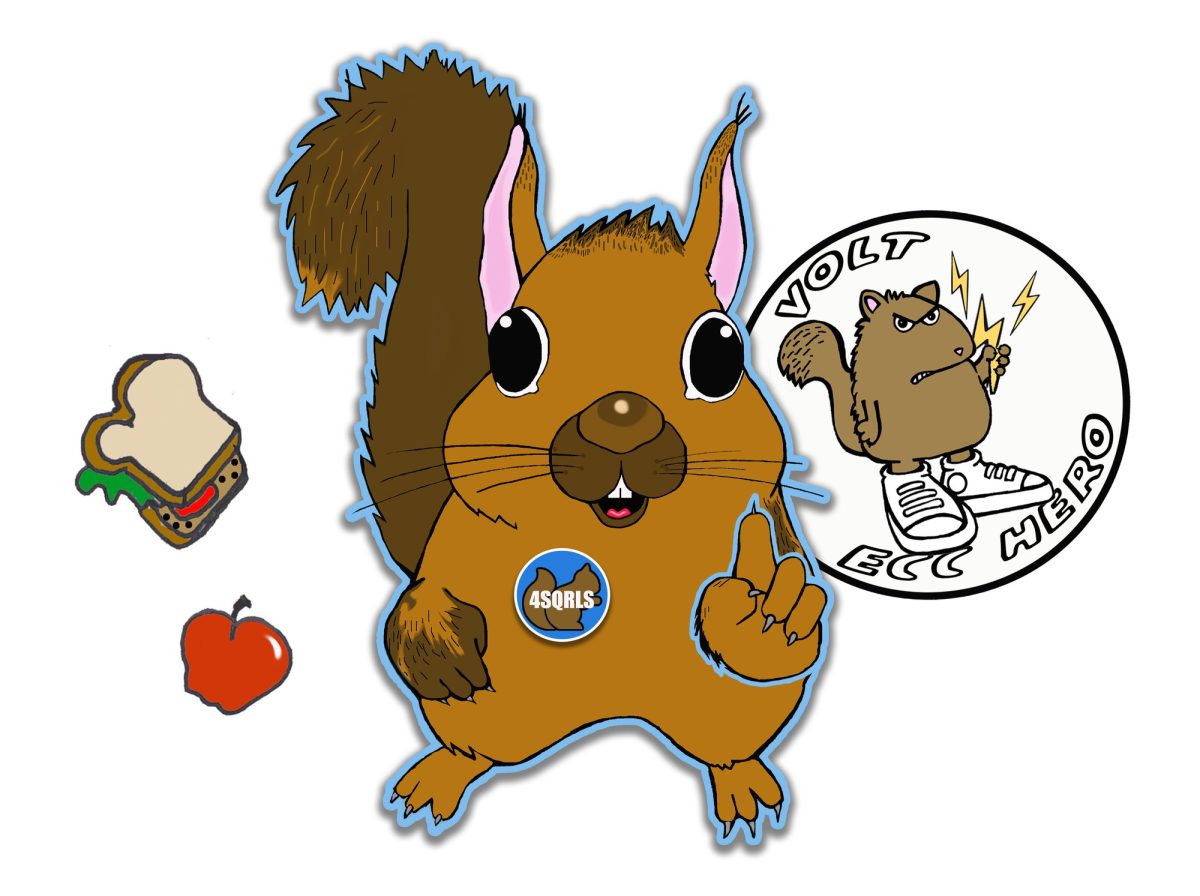

Two weeks later on Dec. 4, The Union newspaper ran an editorial crediting the blackout to a squirrel that student reporters called “Volt” because he “fried” himself – a particularly cruel choice of words – on an electrical transformer on Manhattan Beach Boulevard.

Despite causing $6,500 in damages, students and faculty considered Volt’s “sacrifice” a heroic deed benefiting “everyone who had tests that day or major assignments due.”

The Union urged every student to push college President Tom Fallo to erect a permanent shrine in the squirrel’s honor.

One additional story published on Feb 12, 1998, updated progress on the repairs.

But by the end of February 1998, any discussion of Volt and the honoring of his actions disappeared.

Nearly 30 years later – as the united members of 4SQRLS (For Safety, Quality of life, Right to exist and Liberation of all Squirrels) – we are forced to write this opinion to demand recognition and respect for the contribution of squirrels to the El Camino College community and the planet.

There was no real endeavor on the part of student reporters or campus officials to find out the true name of the squirrel who was electrocuted in 1997 or the motives behind his actions. No squirrel was ever questioned.

For decades we have overlooked this miscarriage of justice and thousands of other microaggressions humans regularly inflict on squirrels.

But over the past several months, the conversation on campus about squirrels has come up in the debates over El Camino’s name and mascot.

While squirrels received the most votes in a 2024 Warrior Life survey of 139 students, staff and faculty on possible mascots, some people feel we aren’t mighty enough to represent the college. One student wrote the hashtag #notmymascot in reference to squirrels.

Once again, it has become evident that the broader campus community has little appreciation for who we are.

In our roles as environmentalists, custodians, providers and protectors, we contribute much to the welfare of others while expecting nothing in return.

To better communicate with you – because, other than humans, animals are not narcissistic – we are using your language and citing your researchers.

Here is the truth about squirrels.

Squirrels are El Camino’s oldest inhabitants.

Fossils record the evolutionary history of tree squirrels back to the Late Eocene Epoch (41.3 million to 33.7 million years ago) in what is now North America and the Miocene Epoch (23.8 million to 5.3 million years ago) in what is now Africa and Eurasia.

Scientists have traced the existence of humans in North America to, at most, 25,000 years ago and the earliest known humans to Africa approximately 2 million years ago.

Today, 268 species living nearly everywhere on Earth make up the squirrel family, including 122 varieties of tree squirrels as well as ground squirrels, flying squirrels, chipmunks, prairie dogs and marmots.

Yes, Disney fans, Chip and Dale are chipmunks and therefore, squirrels.

We would hope that on a college campus – where wisdom is often recorded by years – students, staff and faculty would respect their elders.

You could learn a lot from squirrels.

We disperse spores and seeds, ensuring greater tree growth, as well as biodiversity, throughout the world.

To prepare for a long winter when food is less plentiful, we bury the seeds we find in trees and underground. We mark seeds by rubbing them on our fur to pick up our scent.

Due to our gifts of a strong sense of smell and “detailed spatial memory,” we recover upwards of 80% of what we hide. Some scientists call this squirrel GPS.

We can’t find or return to collect all that we have hidden.

What’s left behind, often grows into new trees.

On a planet increasingly threatened by human-caused climate change and urban expansion, our activities are essential to the survival of trees that in turn remove carbon dioxide from the air and enable all of us to breathe.

We also disperse seeds and spores in our feces, including fungi that remove hazardous toxins from the soil.

Squirrels operate complex communication systems with each other and with other species.

The human publication “Nature” reported on several studies highlighting that “squirrels communicate using complex systems of high-frequency chirps and tail movements” as well as exhibit a wide range of personality traits.

Both features are rooted in genetic strengths that contributed to our survival over millions of years.

For example, squirrels chirp loudly when we feel threatened, often standing on our hind legs or flicking our tails above our heads, to warn others to walk away or prepare to fight.

These actions further warn our families and the larger community of possible danger. Those feral cats that ECC is so fond of would be much fewer in number if we didn’t regularly warn them of approaching coyotes.

We also holler at another squirrel we find attractive. Even as babies, we chirp persistently when we need food.

We are among society’s most effective custodians.

Squirrels mostly eat fruits, nuts and seeds, but some of us also eat insects, carcasses and food trash left by humans.

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, approximately 58% of the methane released into the atmosphere from landfills comes from food waste.

Without us, El Camino would be overrun by rotting food, bugs and road kill.

We are able to eat ingredients rejected by many other species because, through evolution, we have developed a highly tolerant digestive system. In addition, this enables us to survive and thrive in various climates and ecosystems.

It also means that we don’t experience heartburn, so we can’t burp or fart. Unlike people, we don’t create toxic-smelling pollution.

One day, humans might be so lucky, if you don’t destroy the planet before you are able to evolve to the level of a squirrel.

Squirrels are homebuilders.

We create safe spaces for rabbits, other rodents and snakes that take over the burrows we leave behind when we move.

For earthbound squirrels, our tunnels – along with those of rabbits, gophers and moles – aerate the soil, enabling healthier parks, gardens, forests and farms.

We feed the planet.

While we don’t love this fact, squirrels play an essential part in the food chain. We are a source of food for other animals, including snakes, coyotes, hawks, owls and yes – humans.

If you have ever eaten squirrel enchiladas, Kentucky burgoo or Brunswick stew then you already know.

Amazon has several cookbooks featuring squirrel meat, including Collected Squirrel Recipes from Around the World, Laura Sommers’ Squirrel Recipes for the Zombie Apocalypse: A Doomsday Prepper Cookbook to Survive the End of Days, Yvette Fillyaw’s Squirrel Cooking Guide: How To Bring Out The Squirrel’s Natural Umami and Bubba Bonker’s 70+ Squirrel Recipes Cookbook.

Even fancy chefs are promoting eating squirrels as a way to depopulate invasive species, an approach to cuisine called invasivorism. They are referring to squirrels that aren’t indigenous to a particular region.

Don’t get any ideas.

If humans don’t want squirrels to move, stop tearing down forests and meadows to build freeways and mini malls.

Squirrels are transforming the future of human medicine.

According to a research study funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), “ground squirrels have a trait that could help protect stroke patients from brain damage.”

During hibernation, squirrels’ brains experience significantly reduced blood flow, similar to what humans experience after a stroke.

But squirrels wake up after hibernation with no serious effects.

The NIH hopes that by studying squirrels, scientists “could grant the same resilience to the brains of ischemic stroke patients by mimicking the cellular changes that protect the brains of those animals.”

We are teaching humans survival skills.

When we are in danger, we run – fast. Super – super – fast.

But we don’t run straight. We zig-zag. As a result, we have much lower mortality rates than other animals.

A 2008 study published in “The Royal Society” found that some squirrels collect old rattlesnake skin, chew it up, and then lick their fur, creating a kind of “rattlesnake perfume.” This enables them to trick predators who are afraid of snakes and even rattlesnakes who are repulsed by the thought of eating something that smells like both squirrel and their close relatives.

Humans are also learning valuable nutritional survival tricks from squirrels, skills that will become increasingly important with climate change impacting food access worldwide.

Some squirrels hibernate but most of us don’t. We have to store up a huge amount of food to make it through a barren winter. We have developed elaborate schemes to protect our stash.

As reported by the National Wildlife Federation, some squirrels dig holes, pretend to drop a nut in, and then cover it up. Scientists call this move “deceptive caching.”

According to The Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests, other squirrels use “scatter hoarding,” storing their food in hundreds or even thousands of hiding places, rather than losing their whole winter supply to a thief who finds a single location.

In addition, squirrels live almost entirely on a plant-based diet. So, our menu is much healthier for ourselves as well as for the planet. Squirrels don’t have diabetes or heart disease.

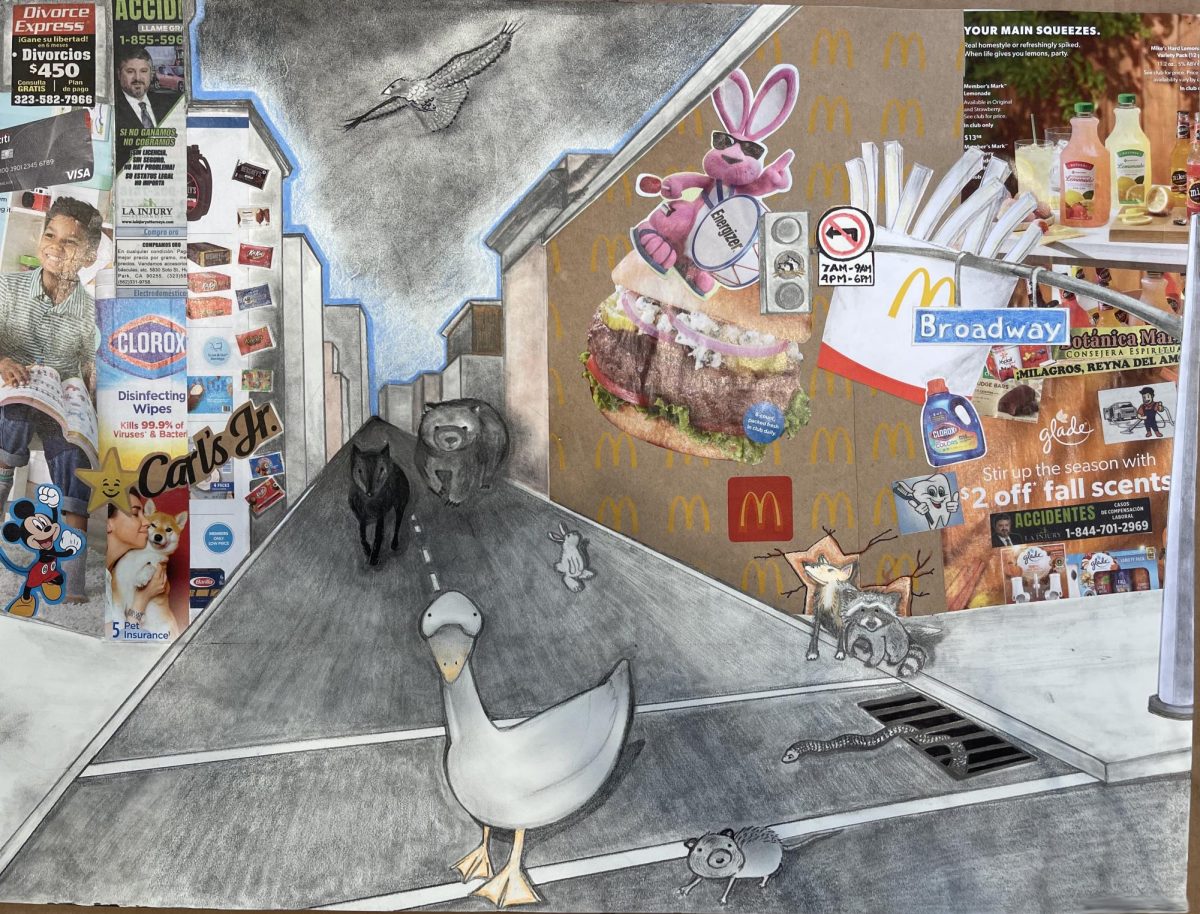

There are occasionally fat and unhealthy squirrels – those that hang out around human tourists and get addicted to fast food. But that’s because they are more human than squirrel, further proving our argument regarding a superior diet.

Squirrels don’t recognize borders.

Squirrels believe in the rights of everyone to migrate, to seek adventure and to build a better life for themselves and their children.

Fox squirrels first came to Southern California with aging Civil War veterans traveling from the eastern United States. Starting in 1904, the vets lived at the Sawtelle Veterans Home near what is now Westwood Village. Probably due to their cravings for squirrel stew, the men encouraged the fox squirrels to multiply.

The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) documented that soon afterward, those first SoCal fox squirrels’ descendants were thriving in Santa Monica. By 1910, the squirrels were in San Pedro, 25 miles away. By the 1930s, they were in Ventura. And today, they are thriving as far east as Claremont.

Because we value migration, we also recognize the benefits of diversity.

There are five species of tree squirrels, just in California. To find out who the squirrels are living near you, check out the Southern California Squirrel Survey.

Today, squirrels travel for miles across the power and telephone lines that stretch out high above California’s roads and highways – another genius skill we have acquired to remain far above our greatest threats: cars, cats and coyotes.

This has the added benefit of further expanding our range, and in turn, our abilities to quickly access safer climates or more plentiful food supplies.

While scampering high above the urban chaos and suburban sprawl, we have constructed no street signs, no checkpoints, no border patrol.

We might defend our food, because without food we die.

But squirrels don’t build walls.

In summary, squirrels are a perfect mascot for El Camino

To all the students, staff and faculty advocating for ECC’s mascot to be a squirrel, we agree.

El Camino was forced to eliminate its racist use of both a Spanish Conquistador and a stereotypical caricature of a Native American as mascots. But, the mission bell currently symbolizing the college is also offensive in its glorification of the genocide and displacement of indigenous people.

We offer an enlightened and inspiring alternative, a kind and courageous mascot that won’t embarrass future generations.

Humans come and go.

But the squirrels at El Camino? We are here to stay.