Every night, homework brought me to tears.

As my Mom patiently read test questions aloud, I’d answer them correctly. But on exams I’d often circle the wrong answer, unable to focus. I was constantly fidgeting, unable to stay still, which made learning an ongoing battle.

I was diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in the fourth grade. As a child, my behavior was pronounced enough to warrant an early diagnosis.

Mrs. Van Duzer, my fourth grade teacher at Center Street Elementary School in El Segundo, California, played a crucial role in recognizing my struggles. She was close to my Mom, who volunteered regularly in the classroom, which allowed her to observe my challenges up close.

It felt like the world moved around at a pace that did not match my brain, leaving me feeling out of place and disconnected.

In the second grade I was put in the advanced math group. We sat on the lunch bench outside the classroom while everyone else stayed inside doing the normal lesson. We were finding sums of 15 on a three-by-three grid.

My peers were knocking it out like it was the easiest thing they have ever done, but I was sitting there with sweaty palms. I could hardly figure out the first row. I didn’t last long in that group, and eventually I was put in the normal math group with the rest of the class.

After much discussion with my doctor, my parents decided to medicate me when I was in the fourth grade, wanting to do what they thought was best for me.

The first year was tough. The side effects from trying different medications were harsh—I weighed only 53 pounds for nearly a year. Adderall was the first medication we tried but it made me irritable and angry.

Many girls tend to be underdiagnosed because their symptoms are presented differently—many are dismissed as “ditsy” before anyone considers ADHD. I was fortunate. We quickly moved on and I cycled through every medication available before retrying a few.

Finally, in the fifth grade, I started taking Vyvanse, and things began to stabilize. I was happier, gaining weight and feeling more balanced.

I received accommodations at school, including extra time on tests and the ability to take exams in quieter, less distracting environments, which made a big difference during those early years.

However, on the days I didn’t take medication, it was a different story. My peers would often ostracize me because of my behavior, which included pacing a lot and talking too loud when I became overly excited. My classmates asked if I was “on drugs,” when ironically, I was not medicated.

My excitement and energy were just natural parts of my ADHD that were often misunderstood. What felt like a rush of enthusiasm to me was perceived as disruptive to others. I was met with judgment and the stigma of “being different,” which led to isolation.

According to an article in Medical News Today, studies show that boys are nearly three times more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD than girls, partly because girls often display more inattentive symptoms rather than hyperactivity, making their struggles less visible.

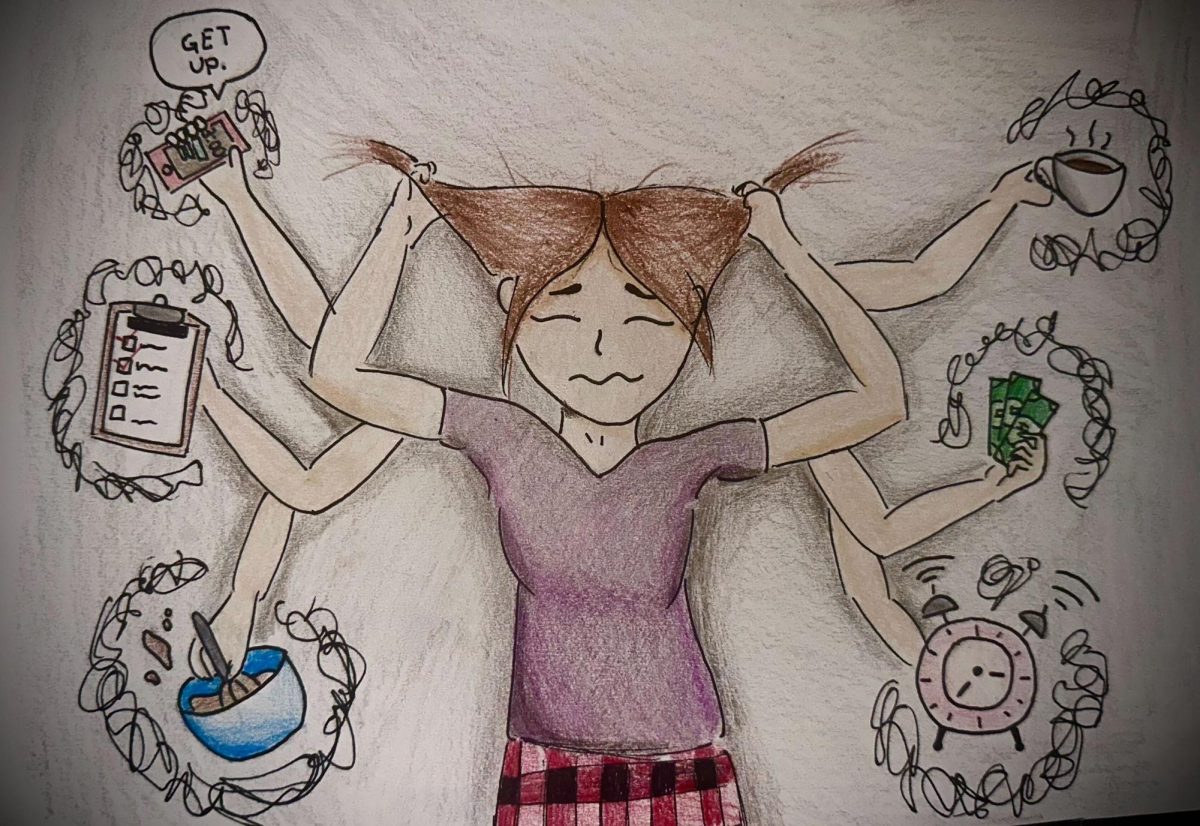

By the time I enrolled at El Segundo High School, the weight of my workload became paralyzing. I’d feel so anxious I couldn’t even start my schoolwork. My mind was always racing, jumping from one task to another–leaving all of them unfinished.

I couldn’t do anything in high school. I didn’t feel accepted by my friends. I didn’t feel accepted by anyone.

Over the past year, I decided to stop taking medication because I no longer wanted to rely on it. I had been taking the meds inconsistently for about a year prior to stopping. Throughout that time, I felt a persistent heaviness on my chest which led me to realize that the medication was exacerbating my anxiety.

It’s been a journey of self-discovery. With the right tools and mindset, I can now manage things on my own.

Although I’ve always hated using traditional planners, I found the Todoist and Opal apps to limit distractions on my phone.

A structured routine has been key in managing my daily responsibilities. Even though there are days when focusing is hard, I have come to accept that ADHD is not something to be “fixed.”

It is simply a part of who I am and I have learned to live with it rather than fight it. Even though I still struggle with big decisions-–like changing my major three times at El Camino College–each change represents a search for something that challenges me and excites my curiosity.

My most recent switch to computer science is reflective of my desire to push myself. This process of trial and error is something I now embrace. My ADHD is not an obstacle, but rather a part of who I am that pushes me to constantly adapt and grow.

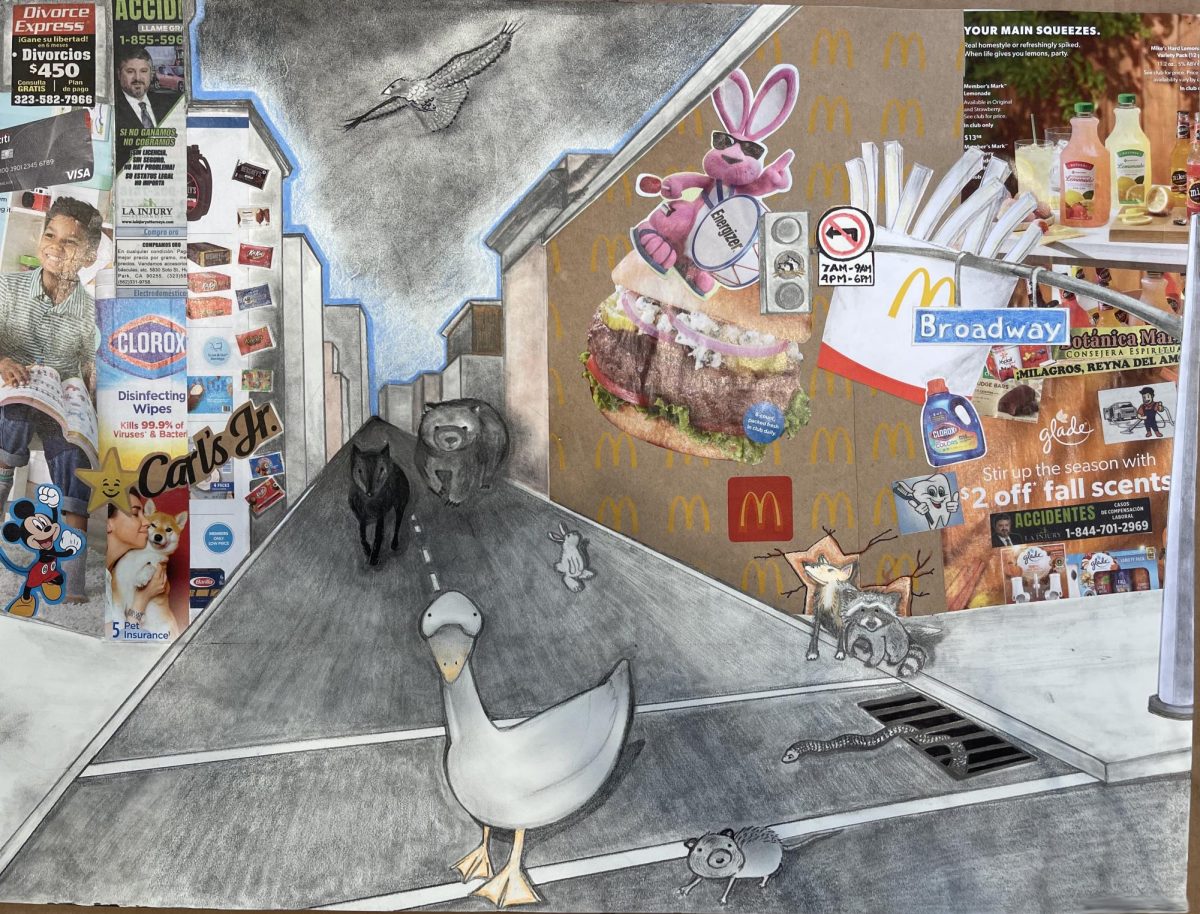

I find myself rediscovering who I am outside of ADHD, no longer feeling chained down by the disorder that once seemed to define me. For years, I carried the fear that ADHD would limit me, but while learning to navigate adulthood, I’ve come to realize that it is just one piece of my identity.

I have learned to live with it, and in doing so, I’ve claimed my sense of potential.

The future feels wide open now—filled with opportunities—because for the first time, I truly believe the sky’s the limit.