Sunken City, San Pedro, serves as a warning for coastal communities

On the inside of the barrier wall that people jump to enter Sunken City — between communities still intact and the desolation of a neighborhood that slid into the sea — a graffiti writer created a chubby-blue water drop with hollow, mournful eyes, seen here on April 22, 2023. The water drop character could be a warning: “Water and shifting lands are stronger than humankind. Try and control us, hold back the ocean’s fury or stop the shifting of tectonic plates, tempt our tides, awaken our fault lines, warm and rise our seas at your own peril.” Kim McGill | The Union

Writer’s Note: This project was supported by California Humanities Emerging Journalist Fellowship Program. For more information, visit www.calhum.org.

Any views or findings expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent those of California Humanities or the National Endowment for the Humanities.

On the morning of April 11, the fog clung to the coast of San Pedro like thick oatmeal that refused to burn off.

At the southern tip of Los Angeles County where the city meets the sea, Point Fermin Park was quiet except for the regular gangs of squirrels battling for trash.

The LA Unified School District School Police circled past more than once searching for students skipping school.

City Parks and Recreation Department staff parked their truck where they could eye anyone there to jump the concrete barrier wall that separates the grassy safety of stable land from the ragged cliffs that drop off to the rocky beach and crashing waves 100 feet below.

Both the police and the park workers had reason to be vigilant. On the left side of the park, beyond the wall and a rod iron gate, lays Sunken City.

The Sunken City has taken the lives of many — some who jump and some who stumble accidentally — over the edge to a brutal death.

A warning for coastal developers

Nearly 100 years ago, there was a neighborhood here, 39 homes sat at the edge of the cliffs to boast the best and closest views of the Pacific Ocean. Built by developer George Huntington Peck, they were coveted as luxury homes and bungalows, the final development of the elite San Pedro Hills.

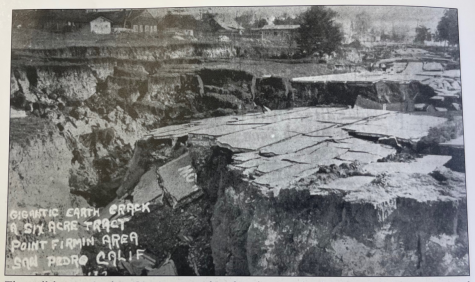

But within a few years of opening, the land beneath the cliffs shifted, a water line and then a gas line broke, and the street cracked and dropped several feet.

Between January and June of 1929, the community dropped over 7.5 feet. An earthquake in July 1929 hastened the movement further.

The community was evacuated. All but two homes were removed. And the area was renamed the Point Fermin Landslide or just “The Slide” by locals.

In May of 1931, William Miller, professor and chairperson of the Department of Geology at the University of California, Los Angeles, published a study of the landslide in Scientific Monthly. “A considerable body of bedrock is slowly moving into the sea,” he wrote.

Miller described the cause of the drop, which came to be known by geologists as a slump.

“Five acres of bedrock on land, as well as a larger portion of bedrock under the ocean, is breaking away from the mainland,” he wrote.

At the time, the fissure Miller measured was 8 to 10 feet wide at the top and “much deeper than the 30 or 40 feet deep that is visible.”

“The fissuring and cracking of the ground have caused a number of buildings to be either wrecked or badly damaged, while others have been moved away. Where the ever-widening main fissure crosses the street, an attempt is being made to keep it filled with dirt,” Miller said.

Just as happened in 2023, developers and engineers scrambled to fight the San Pedro community’s destruction. They filled and re-filled the growing fissures with dirt.

But by the 1940s, all that was left was the crumbling foundations of the remaining two homes and the streets, now sitting more than 50 feet below where they originated.

While Miller’s report places no blame on the decisions made by Peck, government officials and contractors to build a community there, his report highlighted “the fundamental cause of the landslide lies in the character and structure of the rocks. It’s an anticline in a strong seaward dip likely to continue for years.”

“A very dangerous area”

Of the total state population of 38.4 million people, 26.3 million Californians live along the coast.

Increasingly for these residents, the devastation of coastal erosion evident at Sunken City continues in more dramatic and deadly ways today.

April 20, was sunny and warm and yellow wildflowers cascaded down the cliffs at Bluff Cove on the Palos Verdes Peninsula. From the rocky beach, El Camino earth sciences professor Sara Di Fiori instructed her students to observe how erosion was impacting the coastline.

Just south of where her class had gathered, the green and brown vegetation engulfing the cliff side was interrupted by a large section of slate-gray sediment.

That demonstrates where a recent landslide occurred, Di Fiori explained. “Also, that terrace used to have homes on it that had to be moved,” she added, pointing to the top of the cliff.

“One thing that encourages them to slide off into the ocean is not just that they are built on slippery layers of clay, but they (homeowners and developers) also make very heavy, poor decisions when it comes to landscaping,” Di Fiori said. “If you add water to clay, it swells up and if the layers are tilted toward the ocean, you slide right in.”

Geo-engineering — such as the water pipes that were installed into the cliffs to remove excess water from a property into the ocean — can’t hold back the inevitable erosion, Di Fiori explained. After all, erosion has been happening here for millions of years.

“It’s a very dangerous area,” Di Fiori said.

In addition to the erosion that occurs from above, the waves below carve away the cliff side at the bottom. Climate change that is causing both more powerful storms and a dramatic rise in sea level is hastening coastal erosion.

Most recently, this year’s historic winter storms forced more than 20 San Clemente residents to escape their oceanfront apartments as the hill beneath them crumbled into the sea.

Indigenous leaders urge people to act differently

A 30-minute drive north of Sunken City, the luxury development of Playa Vista threatens the Ballona Wetlands Ecological Reserve, home to more than 1,700 wildlife species.

Southern California Gas has storage units and pipelines under the wetlands further endangering the wild land.

Ironically, the wetlands are the most important protector against the dangers of both coastal erosion and flooding due to sea level rise. The wetlands are essential to the survival of the human developments that seek to overtake them.

Gina De Baca grew up in Santa Monica. She has taught indigenous and folkloric dancing for more than 25 years to connect her children and the larger Chicano and Latino communities to their cultural roots.

She remembers the fight against building Playa Vista.

The indigenous people of the region — the Tongva — lived with coastal erosion and respected the power of the cliffs, the beaches and the sea.

“They have a lot to teach us about how to live in harmony with the natural environment,” De Baca said.

But housing developers’ quest to build on every inch of the coast threatens the future of the land, the wildlife and the human communities here, De Baca said. Now million-dollar condominiums rise above the wetlands.

“Our indigenous elders remind us that the earth serves us, and we’re expected to serve the earth. It’s a partnership,” De Baca said.

For that reason, she says, the Tongva should be involved in every decision about development in LA County.

José Gama Vargas organizes with Coyotl + Macehualli (Nahuatl for “people of the city”) to promote indigenous wisdom and experience to protect and restore the environment.

Gama Vargas said the Tongva, his ancestors and other indigenous people who cared for the environment for centuries before colonization must be in leadership to protect the earth.

“It’s why land back movements are so important to return ecosystems to indigenous communities to manage,” he said.

Indigenous nations throughout the Americas including the Tongva often start healing ceremonies by honoring the six directions. The ritual ends by kneeling to touch the earth, calling on Tonantzin to protect the earth and all her relatives.

“Indigenous people remind us that we are connected to ‘Tonantzin’ — Mother Earth. Without her, we are dead,” De Baca said. “We’re not meant to live on other planets. We’re not made from those planets. We are made from the earth and this is our home.”

“Our survival depends on the future of all living things,” Gama Vargas said.

Mother nature has a bigger budget

In the 1980s, the neighbors surrounding Sunken City pressured the city for a fence and regular police patrols, not because they worried about increasing deaths, but to stop “late night trespassers and noisy partygoers” as reported by the News Pilot on March 14, 1986, and in numerous other newspaper articles.

But within three years of installing a $250,000 rod-iron fence, people broke through to reclaim access to the area.

Today, Sunken City is known worldwide as an essential destination for graffiti writers. It’s a favorite spot for couples seeking adventure, people looking for a spot to get high and meditate on life’s possibilities and teenagers too cool for rules or school.

But it also endures as a warning to all would-be developers who prioritize quick profits over the long-term community.

On the inside of the barrier wall that people jump to enter Sunken City — between communities still intact and the desolation of a neighborhood that slid into the sea — a graffiti writer created a chubby-blue water drop with hollow, mournful eyes.

“Water and shifting lands are stronger than humankind. Try and control us, hold back the ocean’s fury or stop the shifting of tectonic plates, tempt our tides, awaken our fault lines, warm and rise our seas at your own peril.”

There are humans sounding warnings also.

Di Fiori stands beneath a sign erected on the beach at Bluff Cove that warns of falling rocks.

“The cliffs have more time and more natural impetus to move,” Di Fiori said.

“They’re not going to care how much money you spend to preserve structures,” she added. “Mother Nature has a bigger budget.”

Editor’s note: Second photo caption corrected on June 8.