Students and staff deserve smaller class sizes

Imagine it’s the first day of college. You arrive early and take your seat in the back of the class.

About 10 minutes before class starts, more students walk in. There are about 25 students in the classroom, and the back is full.

It’s now two minutes until class starts. A rush of 15 students walks into the classroom.

Class begins. There are a few people late–about four students–and there is no desk to spare.

The class size: 45 students.

For some students and professors, this is the reality.

College class sizes need to be smaller so students can build better connections with their peers, learn better and professors aren’t overworked.

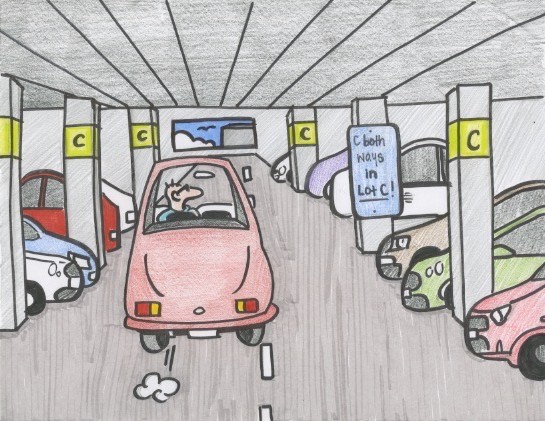

At El Camino College, business classes are one of the biggest culprits in having large class sizes.

According to the fall 2022 semester, there are 67 business classes in the course catalog.

About 66% of those classes are online, with either scheduled class time or asynchronous. The rest are either in-person or hybrid.

Of the 67 classes, only eight, or about 12%, of the classes have a cap of 30 students or less. The largest and most common cap is 45.

Math classes are similar. With 204 classes offered this fall, according to the course catalog, only five classes, or about 2.5%, have a cap of 30 students or less. The cap for the rest of the classes is 35.

It’s no surprise that these two subjects have large class sizes.

Math is general education and sometimes a major requirement. Business classes are popular, as shown in the course catalog.

Even though the demand is high for these classes, having smaller class sizes can benefit students.

According to Brookings, a nonprofit public policy organization, decreasing class sizes of about seven to ten students can have significant long-term effects on student achievement, primarily seen in elementary-school students and students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Although the most significant effects of small class sizes are evident in elementary-school students, that doesn’t mean there’s no effect on college students. It can have a considerable impact as well.

Smaller class sizes mean more individualized instruction. Assignments can be given to help struggling students in the class grasp a concept they don’t yet understand.

Smaller class sizes can mean more hands-on learning. According to Fremont University, one of the best ways to learn is through experience and doing something in class, not just listening to a professor’s lecture.

In large classes, it is nearly impossible to incorporate hands-on learning.

Smaller class sizes build stronger peer relationships. With only so many students, there is an opportunity for students to get to know everybody and build relationships that may not happen in a larger class.

According to Limestone University, smaller classes can also benefit teachers.

With a smaller workload to grade assignments and fewer students to keep track of, they won’t feel as stressed and burned out as they would in a larger class.

They can focus more on struggling students and create assignments that benefit them.

This doesn’t mean colleges should cap all classes to 20 students. College caps are different than high-school caps, which are different from elementary-school caps.

Capping college classes to 30 or even 25 students is an achievable goal for colleges.

The smaller workload and less stress can be motivational factors in hiring more professors and keeping them in their positions longer.

Students going into classes knowing that there won’t be more than 25 to 30 students can make them feel more comfortable and build relationships with their peers and professor.

Creating those networks mean students can help each other, alleviating more weight from the professor.

It’s a positive snowball effect that can make education more enticing and fun for everyone.

With education becoming more enticing, smaller class sizes could help colleges’ low enrollment issue.

There’s always the argument for cost: what about the cost of hiring more professors? That is a legitimate concern.

But is the cost more critical than bettering the lives and education of those professors and students? The answer: no.