Despite the Nite Guard deterrents installed across campus at El Camino College, coyotes remain undeterred and continue to make their presence known. So, perhaps it’s time to readjust our relationship to our four-legged relatives by understanding the reasons for their behavior.

It is true that last year the stray cat, “Don Cornelius,” a long-term resident at EC, met his tragic end at the hands (or paws) of an unknown predator. It’s been assumed that the perpetrator may have been a coyote.

However, EC Chief of Police Michael Trevis dispelled that suspicion when he stated that “it was not definite” the death of the “dean of cats” had indeed been committed by a Coyote.

Coyote attacks on small animals should come as no surprise. Because of the ongoing human encroachment into their traditional hunting grounds and a dwindling food supply, these four-legged animals have been forced into the cities.

Less infrequent but more upsetting kinds of encounters between coyotes and humans can occur. Like the incident at Cal State L.A. last year in March when a wandering coyote in search of food bit a 5-year-old boy in the leg.

The boy survived, the coyote on the other hand was shot and killed by responding LAPD officers.

As troubling as negative human-coyote interactions can be, they are rare. A study published by Utah State University in 2017, Coyote Attacks on Humans, 1970-2015: Implications for Reducing the Risks, reported 367 negative encounters nationwide.

Of the attacks on humans that were documented over a 45 year period, only 165 of those occurred in California and none were fatal. The facts speak for themselves revealing that our ideas about the dangers these animals pose to us may be exaggerated.

Like Native Americans who held coyotes and wildlife in high regard, we can learn to shift our attitudes towards them by learning about the place they occupied in the worldview of the tribes.

The coyote often shows up in folktales as a trickster who imparts knowledge through the mischief he creates, but in others, he is a life-bringing gift giver.

One Kalapuya story tells the tale of “the frog people” who controlled the water resources of the land and were stingy about sharing it until the day a coyote approached them with a deer’s rib that resembled a precious shell.

Tricking the frog people into trading the rib for a drink of water, the frogs offered him a single gulp.

“But I may take a very long one,” he said to them.

And doing so, with his head and paws beneath the water, he pierced a hole through the dam.

The great deluge of water that was let loose spread across the land, creating the rivers and streams for the people who’d been denied its access before.

There are other creative ways EC can address the concerns over coyotes visiting campus grounds while paying the same kind of respect the story above illustrates.

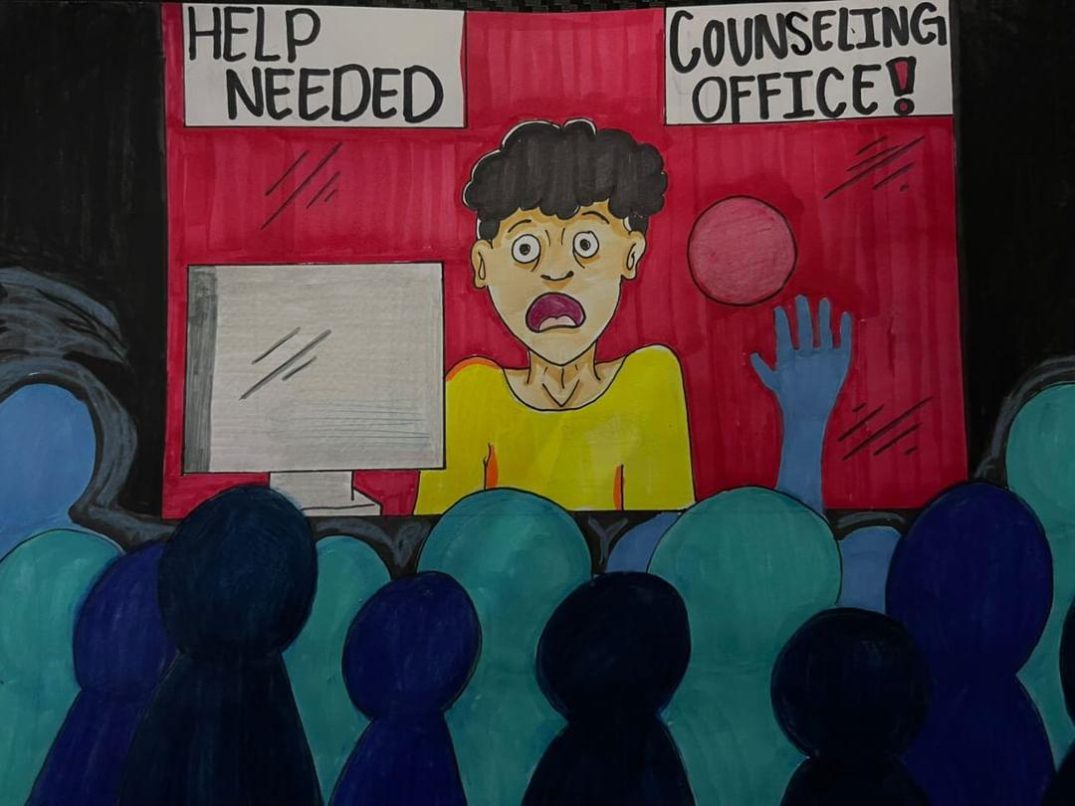

In addition to the deterrents currently in place, EC should consider adding interpretive signage posts around campus. Through visuals and snippets of information, such posts can educate students about the wildlife they may encounter in school.

Additionally, these can help promote safe practices around other fauna-raccoons, opossums, squirrels, coyotes, even hawks—as well as deepen our understanding of them too.

After all, at one time or another, we have all expressed some awe, admiration or the slightest bit of curiosity in silence or out loud, at the sight of our four-legged relatives. In some ways, they are here for us.