Bullet-sized raindrops crash on a cobalt-blue tarp like a snare drum, drenching everything in sight.

The water level of a nearby runoff to the LA river rises. The runoff forms a massive tunnel that flows underneath the west end of the El Camino College campus.

On dry days, the canal serves as a haven for a homeless encampment that seeks refuge inside of it. Today, it is their worst enemy.

They must rush to higher ground before all their worldly possessions or worst, themselves, are swept away with the rapid and rising current.

Eddie Pili has moved all of his belongings to higher ground and covered them with the tarp.

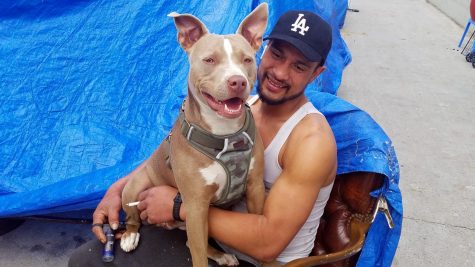

He stands on one leg, limbs spread out like a starfish. The outline of his nipples peeking through his semi-translucent A-shirt, mimicking tissue paper more than an article of clothing. Eddie’s crooked smile stretches from ear to ear. His black Dodgers’ cap, slightly tilted to the right, exposes a single white wireless earbud with a Tommy Hilfiger logo in his right ear.

He is covered in dirt and grime and soaked to the soles of his red sneakers. He wears three layers of pants, each sagging below the other like an upside-down bandage dress. With his A-shirt tucked into his boxer briefs, every inch of his body is strategically covered except his sun-burnt arms.

The rain, nor the imminent danger of a potential flash flood, seem to elicit much of a response or panic from Eddie. Perhaps the routine of it all is so commonplace that the dangers are no longer as perceivable or threatening. Or perhaps Eddie chooses to see the silver lining of it all.

“God’s blessings are like the rain, he showers you with them!” Eddie euphorically shouts, looking up at the sky.

This is not Eddie’s first day dealing with the severity of life. And much like others in the transient community, Eddie will be on the move soon. This brief but memorable moment will be one of the few and perhaps even the last that anyone from the campus community will be able to document. This is a day in the life of Eddie Pili.

At the El Camino College police station, office Erika Solorzano, a 12-year-veteran of ECPD, talks about several of her interactions with the transient community on campus and the adjoining Alondra Park, a 53-acre regional community park that shares a boundary with the college campus. Erika says that for the most part ECPD and its officers try their best to help the transient community in the tunnel that run underneath Lot F.

“We do some little care packages, you know of goodies and stuff, so we help them,” Erika says. “We’re not in the business here at the college to say, ‘hey, we’re gonna take you to jail. We’re here to help them get help. We have resources on campus through the Help Center that we’ve provided. We have resources through other local agencies, like Gardena. We’ll refer them to homeless shelters and to the officers that are doing the crisis needs within those departments.”

Erika pauses and re-adjusts her mask and Kevlar vest. She says that since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic that sightings of the transient community have all but diminished on campus due to the lack of facilities and students. On days of heavy rain, she and her fellow officers make trips to the tunnel to warn the homeless community living under it.

”With the heavy rains and stuff, you do get flooding down there,” Erika says. “So the sheriff’s usually come in and ask all the homeless that live underneath the channel to, ‘hey, get out! If you don’t, you’re risking the possibility of getting flooded and dying.’ In my tenure here of 12 years I’ve heard of two that have drowned, and many rescues up and down the channel. It is something that they know is a risk factor of being down there.”

At the runoff, water from the drains and sewers on campus has stopped pouring into the tunnel. The rain begins to subside and the clouds part. Eddie is soaked from head to toe, but begins to share his story.

Eddie was born in American Samoa, which established its status as a U.S. territory in 1900. Unlike other U.S. territories, American Samoa is a “glaring exception” for not offering citizenship to its residents according to the ACLU. They describe the United States’ relationship with the population of American Samoa as, “an obscure and discriminatory status as ‘non-citizen nationals.'”

Eddie starts to walk down the ramp, moving closer toward the mouth of the tunnel. He riffles through his pockets to find a cigarette. Eddie remembers his life on his native island. He says he misses American Samoa and his family, and that he is looking forward to Facetime-ing with them later.

He pulls out a soft pack of Winston Red 100s and recalls how he never wanted to leave his home or rich culture behind. Eddie says at the insistence of his grandmother he packed up his life and moved to Southern California in the hopes to find better opportunities and improve the circumstances of his life. Eddie’s grandmother lives nearby in the South Bay and he says he visits her weekly.

He also has a little brother in the U.S. that he wishes he could visit more often. Eddie says his brother lives further away in “the monkey house,” a term he uses to describe prison.

Eddie pats the front of his sweatpants just before rifling through his pockets to find a torch-style cigar lighter. Again, he meticulously adjusts his cap. Double-checking if it is perfectly tilted on the right side of his head. He begins to mention how he began living in a tunnel, and how this was a “short-term thing” for him. He then transitions to how he got introduced to drugs and shortly thereafter found himself homeless. That was four or five years ago by Eddie’s estimation. He has been living under tunnels like this ever since.

Eddie raises his right hand to his face. There is a noticeable wound just above his knuckle. He places a cigarette in his mouth and presses its filter between his lips. Mumbles of half-enunciated words spill out of his mouth as he tries to speak simultaneously. The cigarette, all the while waggy like the tail of an eager white pitbull, barely hangs onto the end of Eddie’s face. Realizing his lack of elocution, Eddie clamps the cigarette between his middle and index finger and holsters it at his side. He repeats the phrases, mentioning how badly he wanted to join the military from a young age. Eddie says if it wasn’t for the pleas of his mother’s not wanting to see him injured or killed in combat, that he would have happily joined the armed forces.

Eddie scratches his face while stepping out of the slight shadow of the tunnel. His right hand now more noticeably swollen and beet-red in the light. The symptoms originate from the infection above his knuckle. An ebony-colored band strangles the circulation to his swollen ring finger, causing it to swell like an overly plump kielbasa. Eddie says that after his dream of joining the military was crushed, he decided to listen to his grandmother’s advice and come to the U.S. He pursued an education in mechanics, and took classes at a vocational school, UEI, here in California.

As Eddie’s dirt-caked fingers bring the pristine-white cigarette back up to his lips, he recalls the stresses of classes, expectations and promises he made to his family. Eddie says all he wanted to was to blow off a little steam and fraternize with his classmates. He says it started with having a few beers with new friends, and maybe occasionally smoking a little weed. But Eddie vividly recalls the first time that he was introduced to “dope” at a party while in school. That was the day that cocaine changed his life.

“When I got here I never touched drugs. The only drugs I was using was weed and liquor,” Eddie says. “When I got into the States, I see dope and cocaine and I’m like, ‘alright. Why not?’”

As he reflects on how drugs lead him to this point, Eddie obsessively begins fidgeting with his cap again. His tics and mannerisms intensifying more as he talks about his substance abuse. Once his cap is perfectly placed and positioned he exhales a sigh of relief and breathes in deep as he closes his eyes.

He ignites the torch and lights the tip of the cigarette. As he takes a long drag the bright orange ember begins to glow. As Eddie exhales the white cloud of tar and nicotine-laced smoke, his dog “Mama” trots up to be petted. Eddie isn’t alone in the tunnel. Mama is constantly by his side.

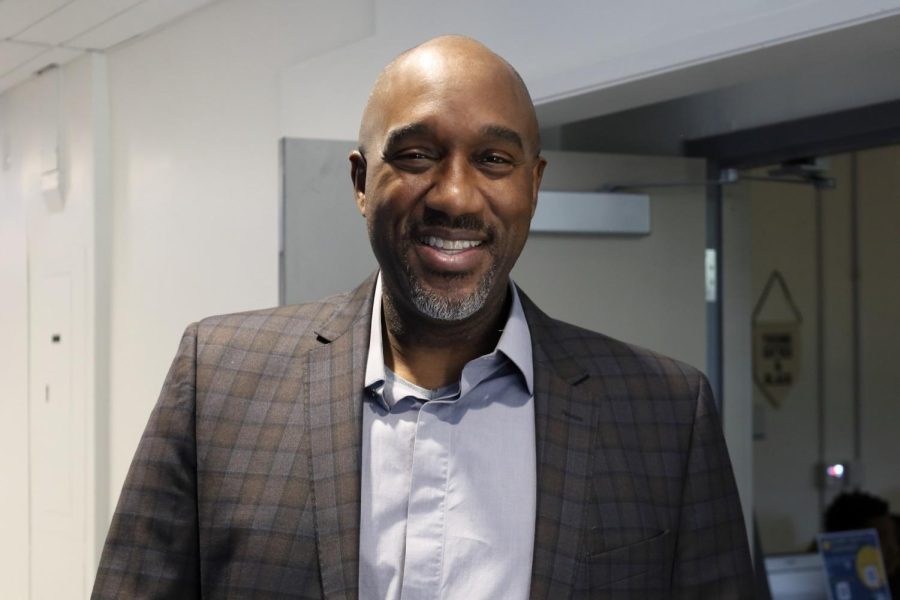

The contributing factors to homelessness are vast. From mental health issues, to affordability of housing, to socioeconomic reasons and substance abuse. Benjamin Henwood, associate professor at USC’s Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work and the director of the Center for Homelessness, Housing, and Health Equity Research sheds light on some of the more common contributing factors affecting people of color in the homeless and transient communities.

Benjamin says that a study done by the Department of Public Health shows that there are higher mortality rates in the white homeless population in Los Angeles than in homeless populations of people of color. According to Benjamin, this shows that the white homeless community is more often homeless due to health reasons than the lack of social capital.

“[Having social capital means] people in your network who have access to resources and opportunities, provide more resources and opportunity for you,” Benjamin says. “In communities of color, oftentimes they’re just less resource and [individuals] don’t have the same opportunities.”

Benjamin passionately explains how lack of opportunities and social capital, along with the consequence that comes from the lack of these pivotal factors, disproportionately affects people of color

“Are there racial differences and risks related to substance abuse? I think we know that there is,” Benjamin said. “The difference between cocaine and crack and their sentencing guidelines is that if you work in finance, and you have an addiction issue related to cocaine, you’re less likely to get arrested. And if you do get arrested you’re less likely to have it have as big of an impact on you. On the other hand, when you live in a community where crack is more readily available, the sentencing guidelines are much higher. So I think the issues that lead to substance abuse don’t really discriminate as much, but I think the social consequences of those things do.”

The ember of Eddie’s cigarette nears the filter. Just before he uses his thumb and middle finger to flick his cigarette butt away, his eyes turn red and well up. As Eddie stares into the distance, his thoughts thousands of miles away, he begins to talk about his mother and says that on normal days when he is not high, he is like any regular person.

Eddie recalls one time when his mom called him and he was high. He said that she could tell that there was something wrong in his voice. Eddie said he still feels bad about that day and makes sure he only answers his phone when he’s sober.

As the warmth from the sun beams down and dries up all the rain, Eddie picks up his pitbull Mama and walks out of the tunnel and back over to the tarp covering his possession. He sits in a mahogany-colored wooden dining room chair with Mama on his lap. In the direct sunlight, one can see the green-grape hue of Mama’s unconditional eyes and she begins to lick Eddie’s face.