Part-time instruction grows as enrollment increases; faculty union officials push for more full-timers

Kelsey Iino spoke out in support of the El Camino College Federation of Teachers during the May 15 Board of Trustees meeting. Iino said while she can sympathize with the tough budgetary decisions administrators at El Camino College have to make, she would always encourage even further efforts to increase full-time faculty, both at faculty and classified levels. (Khoury Williams | The Union)

Last semester, international student Thwin “Kit” Minyan, 19, took an online math class taught by a part-time instructor. The computer science major said his professor would not communicate, leaving him to self-study.

He does not think this issue is unique to online classes.

“I wish professors and I could have more communication,” Minyan said. “Even on campus … some of them don’t have office hours.”

Chris Lopes, 23, used to attend Compton College and now works there in a part-time, non-academic role. He now attends El Camino and is studying radiologic technology.

Due to difficulties he has experienced in his own job, he is sympathetic to part-time professors. But even while he cites a history of excellent instructors he would have liked more interaction.

“But I would prefer more office hours, more chances to visit a professor,” Lopes said.

The data

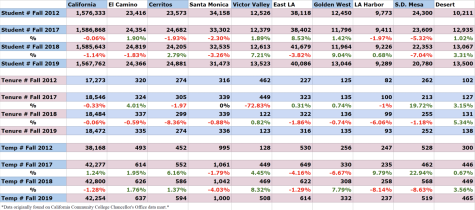

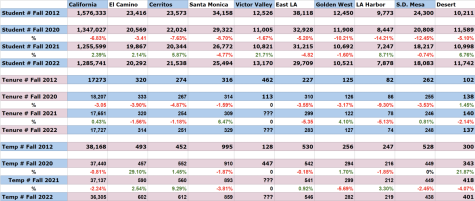

Part-time/temporary faculty increased 32% between 2020-2022 at El Camino, at a faster rate than the California average which saw a 3% drop in the same positions.

El Camino and statewide student enrollment saw a 2% rise last year, per data found on the California Community College Chancellor’s Office data mart.

California has experienced a 4% overall loss in enrollment between 2020 and 2022 while El Camino has only seen a 1% drop. Statewide student enrollment dropped 21% between 2012-2022, El Camino dropped 13%.

Statistics cited in a presentation about enrollment strategies given at the May 15 Board of Trustees meeting indicated an initial rebound of students began in fall 2022 and continued through spring 2023.

However, retention rates generally declined through 2018-2021.

Meanwhile, full-time faculty decreased by nearly 6% between 2020-2022 at El Camino compared to a nearly 3% drop across California, according to Community College Chancellor’s Office data mart.

College increases part-time hires

“We are growing and that’s really good news for us and that also means we’re bringing back more part-time faculty in order to meet the student demand and accommodate the surge of enrollment.” Vice President Academic Affairs Carlos Lopez said.

While tenure or full-time positions can take six to eight weeks to fully process, Lopez says temporary positions can usually be filled much faster.

As emergency funding is set to expire after 2025, Lopez said colleges are incentivized to attract and retain students.

Nearby, Cerritos College also increased temporary instruction and is experiencing an enrollment bump, something Santa Monica and East LA colleges are not seeing.

Academic Senate President Darcie McClelland said in 2020, as enrollment and available classes decreased, temporary workers were let go to accommodate full-time instructor minimum workload.

“A part-time faculty member is not allowed to be offered a class unless every full-time faculty member in that area already has a full load,” she said.

McClelland describes the pandemic years as a “perfect storm of events” where the school did not hire and many full-timers retired leading to an exodus of part-time workers in the short term. As enrollment grew the part-time roles increased to accommodate.

While the recent increase in part-time faculty may seem drastic, looking at data points before 2020, Human Resources Director Maria Smith said she can see the current tenure and temporary faculty numbers are not too far off from 2019.

She said El Camino has always hired a lot of temporary instructors. As full-timers retire or leave that leaves multiple open positions.

“If you have one person who leaves five classes, you may have to hire three people to replace that one,” Smith said.

Lopez said the part-time increase was necessary to accommodate enrollment. Next semester however he said the college had approved 25 new full-time hiring positions, two full-time categorically funded positions, four one-year full-time temporary positions and eight one-semester full-time temporary positions.

The new positions are not filled as of yet, but rather those roles have been approved to be filled for next semester.

Lopez said the plan is to use money from state-allocated funds to further increase full-time positions as time goes forward.

President of the El Camino College Federation of Teachers and counselor Kelsey Iino said she can understand Lopez’s and the administration’s point of view and says the increase in part-time hours makes sense for flexibility.

“But I would always encourage more full-time permanent employees in general, whether that be instructional or classified, it just creates a better work environment and job security,” Iino said.

Iino also brought up retention rates and how a structured full-time faculty can help make students want to stay. She said temporary work can affect professors too and cited her own experience of working at three different schools and still bartending.

“Within reason, I think we can get to a higher number of full-time and a lower number of contingent faculty. I don’t know what the number is, and maybe we’ll make a better effort at it once we’re up over the (enrollment) bump,” Iino said.

Increasing full-time instruction

Evan Hawkins, executive director of the Faculty Association of California Community Colleges said mandated incentives are already set up to help districts increase their full-time and part-time instruction ratios, but they don’t always work.

Concerning El Camino’s approval of over 25 full-time positions, he had praise, even while warning not to rely too much on full-time temporary positions.

“El Camino may be doing the right thing,” Hawkins said. “I think that’s a step in the right direction.”

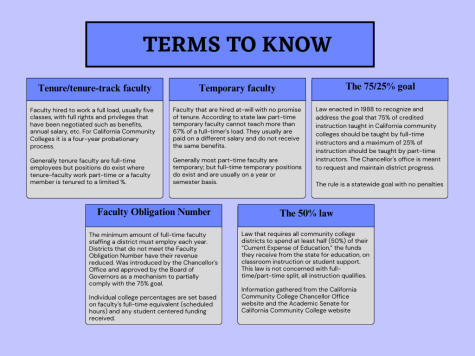

He said the 75/25% rule established in 1988 was meant to encourage community colleges to strive for more full-time instruction.

“The funding model in the state is not designed right now to support 75/25, which is why it’s a goal, “ Lopez said. “It’s a noble goal but the way the current funding structure and the current funding realities in our system make it very difficult … If the financial structure of the system changed, then maybe those percentages could shift, but those are statewide dialogues.”

The Union was not able to verify the official 75/25% from El Camino College but by using the chancellor data mart individuals can find a college’s academic full-time equivalency or working instructional hours and determine their school’s 75/25% ratio.

El Camino scores 52/48 in terms of a full-time and part-time instructional split.

It must be noted this number is an estimate that is based on assuming the figures given by the database are correct.

While Hawkins is sympathetic to the realities faced by administrators he said the problem with the goal is there is no concrete penalty to comply.

“There’s no enforcement,” Hawkins said. “The intention is that there is a lot of research and data showing that students can be more successful when interacting with a full-time faculty member.”

Instead, the Faculty Obligation Number was created to help the state and the district reach 75/25%.

The Faculty Obligation Number does have a penalty; colleges that do not comply receive reduced funding for instruction. But Hawking thinks the Faculty Obligation Number has become the goal rather than the tool to reach 75%.

“It was supposed to be a minimum right so it was supposed to be sort of a floor but most districts use it as their benchmark,” Chemistry professor at Merritt College Jennifer Shanoski said.

Shanoski is also the vice president of the Northern California Community College Council of the California Federation of Teachers as well as the president of the Peralta Federation of Teachers.

Shanoski said increasing full-time instructors helps students and allows faculty to perform support services outside the classroom during lab, office or committee hours.

No easy solutions

Hawkins cited a recent 2023 report from the California State Auditor’s Office which found some districts mismanaged their statewide allocation of $150 million that colleges were supposed to use to increase full-time instruction.

Per the audit report, “two of the districts we reviewed did not always use the funds properly. Further, the remaining two districts’ methods for spending and tracking the funds did not provide adequate assurance that they had used the funds as intended.”

The audit recommended improvements to colleges, districts and the Chancellor’s Office.

El Camino was not audited in the report and it has met its faculty obligation. While the 75/25% split eludes El Camino, other schools have failed to consistently reach it.

Even legislation is not a guaranteed fix. Two failed California bills, AB1505 and SB777, were meant to help enforce 75/25%. The issue received attention but the bills did not pass.

“Of course, the downside of it is not just that it hurts students by not having as much access to full-time faculty, but basically, budgets are balanced on the back of temporary faculty,” Hawkins said.

Back at El Camino, Minyan says he can see both the college’s and professors’ point of view and doesn’t think it’s anyone’s fault. But Lopes’s idea of how to increase full-time instruction echoes the words of Iino and other faculty.

“I think it would help out if you increase full-timers, I think full-timers need more incentive,” Lopes said. “Better compensation, better pay, stuff like that.”