Justice for Cookie: How the murder of El Camino College student Juan Hernandez turned his mom into a powerful leader in the growing movement to heal families and communities

On Sept. 22, 2020, 21-year-old El Camino College engineering student Juan Hernandez – known to his family and close friends as “Cookie” – left the apartment where he lived nearly his whole life with his parents and brothers on Adams Boulevard in South Central Los Angeles to drive to his job at VIP Collective Marijuana Dispensary at 8113 S. Western Ave.

He never came home.

This is not only a story about a missing young person. It’s also a story about a woman who pushed one of the nation’s largest police departments to find her son, and in the process transformed from a mother to a witness, an investigator, a healer and eventually, a warrior.

The witness

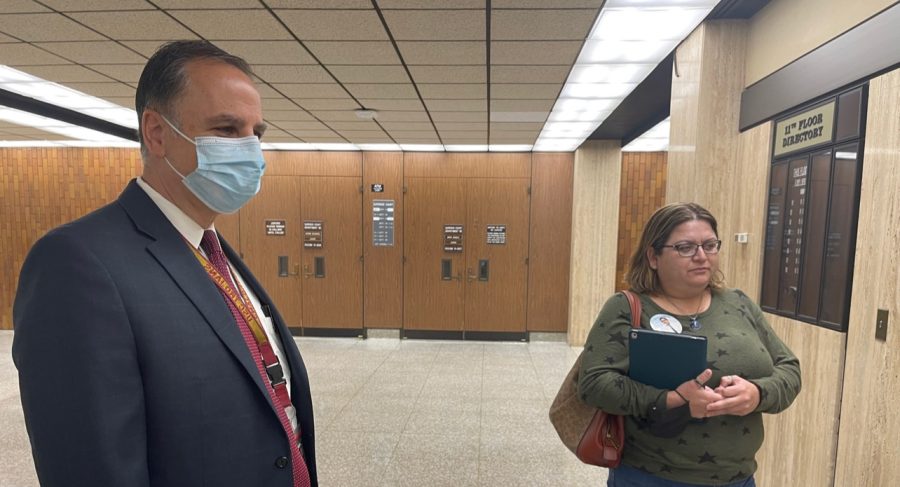

On February 28, 2022, Yajaira Hernandez stood outside Department 41 at Clara Shortridge Foltz Criminal Justice Center in downtown Los Angeles.

Known on the streets and by those who work there as Criminal Court Building or CCB, the massive concrete structure is the largest courthouse in the U.S., with 61 courtrooms and 101 holding cells.

Everyone, no matter how powerful, seems small and insignificant amid the worn marble and tacky wood paneling of its hallways and departments. Thousands of people come and go each day. While things slowed dramatically during COVID-19 lockdowns, Yajaira Hernandez was still among more than two dozen people waiting for their cases to be called.

Her lower face was covered in a black disposable mask – a reality of life under the pandemic – and her brown eyes peered out from behind black rimmed glasses that perched on top of the mask’s upper edge. Her light brown hair was combed neatly to the side, and blonde highlights brushed against her shoulders. She was dressed in a dark jacket and black and white plaid blouse.

She came to court alone, unlike most of the people leaning on others for support or quietly talking.

“I come here so my family doesn’t have to. I want to save them from any more pain,” she says.

Around her neck, she wore a silver chain and heart-shaped charm decorated with a photo of Juan Hernandez, her middle son.

The resemblance between Yajaira Hernandez and her son was uncanny – the same features, same eyes, both wearing glasses – except that in the photo Juan Hernandez was smiling and his mother’s eyes expressed both a fierce determination and a deep sorrow.

Officially, she was in court as a witness for the prosecution in the preliminary hearing of The People v. Ethan Kedar Astaphan. Astaphan is one of three defendants charged with the killing of Juan Hernandez.

Unofficially, she was there to ensure that the County of Los Angeles would effectively present the evidence she pushed the Los Angeles Police Department to collect.

Juan Hernandez’s murder had happened nearly 18 months earlier, but the LAPD and L.A. County District Attorney’s Office had not communicated much to Yajaira Hernandez about the case.

She was afraid of what she would hear in court, but also anxious to learn about her son’s last hours, including why and how he was killed.

Her disappointment was obvious when she was told to leave the courtroom. With the exception of the law enforcement officers who lead the investigation, all other witnesses are barred from preliminary hearings and trials in order to protect the integrity of their testimony.

It’s only through reporting by The Union, the student-produced newspaper at El Camino College, that Yajaira Hernandez learned that her son was allegedly murdered by VIP’s owner Weijia Peng and store manager Astaphan, that they dragged Juan Hernandez, possibly unconscious and alive, from the dispensary into the back of an SUV, that while Peng’s girlfriend Sonita Heng drove east to San Bernardino County, Peng and Astaphan injected Juan Hernandez with a lethal dose of Ketamine, then dumped his body off a dirt road in a desolate section of the Mojave Desert, that – as daylight broke – they arrived back at the dispensary to remove evidence and clean the location where Juan Hernandez struggled on the floor while being choked, and that later in the day they burned his belongings on an Orange County beach.

The weight of this information caused her shoulders to slump, and her eyes shifted downward, but she did not shed a single tear.

On May 3, 2022, Yajaira Hernandez was back at court. She was wearing an olive-green sweater with black stars. A large button with Juan Hernandez’s photo was attached just below her left shoulder. She looked tired and her voice was low and somber.

She was frustrated that the process was so slow.

“People don’t realize that this process is draining. Having to be strong for everyone is exhausting, emotionally and spiritually,” she says. “I wish this system was built differently.”

The prosecutor on the case, Los Angeles County Assistant District Attorney Habib Balian, told her that she doesn’t have to come to every court date. But she said she needs to be there as much as possible to represent her son.

There are still many months left in the proceedings.

Peng, who was extradited from Turkey where he fled not long after Juan Hernandez’s disappearance, did not appear in court until Nov. 21, 2022, for his arraignment.

Pre-trial hearings were regularly held in December 2022, and during the first five months of 2023 to give both Astaphan’s and Peng’s attorneys time to review evidence and prepare a defense. A trial could start in the summer or fall, but that’s what the D.A.’s office said last spring.

Nothing is certain.

Peng, now 34, remains in custody on $20 million bail and Astaphan, now 29, is detained on $10 million bail. Heng, now 23, is out of custody on a plea agreement that includes her testimony as a state witness against Astaphan and Peng.

On January 9, 2023, Astaphan’s defense attorney, L.A. County public defender Larson Hahm, informed the court that Astaphan was married in December 2022, and with permission of the judge, he took a photo of Astaphan in order to process a new I.D.

On April 4, 2023, Balian said that LAPD Detective Daniel Jaramillo – one of two detectives who investigated the case – was promoted to serve as assistant to LAPD Chief Michael Moore.

Balian also joked about looking forward to his own retirement.

Life has moved on for most involved in the case, but not for Yajaira Hernandez, who struggles to heal from the murder of her middle son. For the family members of people who disappear or are murdered, progress and joy is frozen in time, she said.

“I’m going to live with this pain forever,” Yajaira Hernandez says. “We should be able to lay my son to rest, pray for his soul and move on. Instead, we’re praying – and fighting – for justice.”

The investigator

“I knew immediately that something was wrong,” Yajaira Hernandez says about the morning of Sept. 23, 2020.

She woke up at 5 a.m. She always checked her boys’ rooms first.

Her youngest son, Gabriel Hernandez, was still sleeping. When she looked into Juan Hernandez’s room, his bed was still made, and she says an ominous sensation overtook her.

She rushed outside and found that her car was also missing.

“Juan had never not come home. He never ran away. He was never late without a call or text. And I knew he would never take off with my car,” Yajaira Hernandez says.

He knew how much she depended on her car to get to work.

She checked her phone. She had no missed calls. No texts. Her son didn’t respond to any of her attempts to reach him.

She then called her sister Stephanie Pineda and her boys’ stepfather Mike Burka and asked them to come over.

She called other family members and friends to see if anyone had heard from him. No one had.

His best friend said that they were supposed to meet up, but Juan Hernandez never showed.

Yajaira Hernandez called the dealership where she bought her car and asked them to track it. They said only the police could do that.

She was becoming frantic. She began to run through possible scenarios. Maybe he’s stranded somewhere without a phone charger. No, he can charge his phone in the car. Maybe he’s been robbed and hurt. Maybe he smoked some weed that was laced with a dangerous substance and he is sick or sleeping it off. Maybe he’s in trouble and afraid to come home.

Yajaira Hernandez made a bargain with her son in her head.

“I kept thinking, just come home. No matter what has happened, we can deal with it,” she says.

Pineda and Burka drove to the VIP Collective. They spoke with a security guard they described as a tall, slim, Black male.

Warrior Life confirmed through the physical description, court testimony and evidence presented at a later court hearing that the person they spoke to was Jalen Commissiong, who another employee, Daniel Romero, referred to as “T.” According to Romero, Commissiong worked as VIP’s security guard six to seven days a week from 8 a.m. until closing at 10 p.m.

“Juan left yesterday and we haven’t seen him,” Commissiong says to them.

While her family was at VIP, Yajaira Hernandez called the Southwest Division of the LAPD.

They refused to take a missing person report. They told her that her son was an adult and had a right to disappear without checking in with his family. The police said she had to wait at least 48 hours.

At noon, Yajaira Hernandez, Pineda and Burka drove to the LAPD’s Southwest Division on Martin Luther King Boulevard. Again, they said they wanted to report Juan Hernandez as missing.

The LAPD still refused to investigate it as a missing person case. Young people take off from home without calling their mom all the time, the police said.

Yajaira Hernandez says that the LAPD’s indifference both angered and terrified her, but she was a tough mom who had raised three boys and she was convinced that something horrible had happened to her son.

“Then I want to report my car missing,” she says.

She pushed the police to take the report.

“I wanted the LAPD to help me. I wasn’t going to sit there and do nothing,” she says.

At about 3:30 p.m., Yajaira Hernandez, Pineda and Burka went back to the dispensary. All three went inside and Yajaira Hernandez spoke to Commissiong.

“We closed at 10 and he [Juan Hernandez] left,” Commissiong says to them.

Yajaira Hernandez kept questioning him. Commissiong said he couldn’t remember which way Juan Hernandez went, if he was walking or driving, or who else was there when he left.

Yajaira Hernandez then said she needed to speak to E., referring to the store manager Astaphan.

“Call him or give me his number,” she says to Commissiong.

According to Yajaira Hernandez, Commissiong told them the store didn’t “want any trouble” or want “anything to do with the police.”

She felt that Commissiong was holding back. She thought he was being evasive, refusing to answer questions and becoming increasingly short and aggressive.

“He was rude. You would have thought they [VIP] would be worried,” Yajaira Hernandez says.

Juan Hernandez never missed work, but no one at the dispensary seemed concerned that he wasn’t there. Astaphan sometimes drove her son home from work, yet he hadn’t called to ask about him.

“I knew something was wrong,” she says. “They were being very sketchy.”

Yajaira Hernandez went to a nearby liquor store with her son’s photo. The staff immediately recognized him and said that he came in every day for snacks. They offered to post a missing person flyer once one was created and promised to ask customers if anyone knew anything. She says this is the kind of response she would have expected from VIP unless they were hiding something.

When she returned to the dispensary, Commissiong didn’t want to let her in.

By the time they arrived back home, Yajaira Hernandez was in full detective mode.

“I felt I had to do the work that the LAPD was refusing to do,” she says.

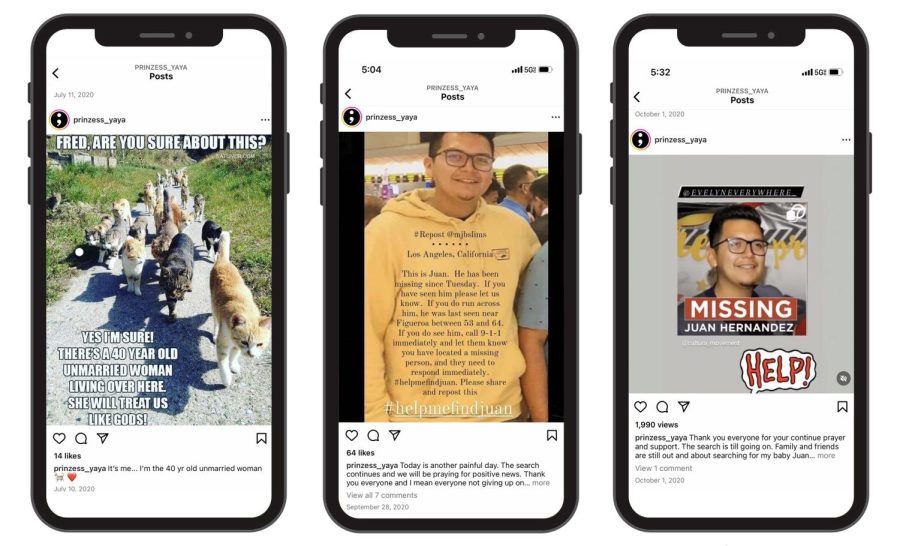

Juan Hernandez’s older brother Joseph Hernandez posted a message to Instagram and Facebook. Yajaira Hernandez shared it with all the school and community groups their family was a part of – the PTA, robotics club, a neighborhood academic enrichment program run by USC, and the running groups Juan Hernandez and his mom had been a part of since he was 14.

“We had a great response from family and friends,” Yajaira Hernandez says.

People started to share the post and asked what else they could do to help.

Yajaira Hernandez’s phone number was included on the post and, within 24 hours, she started getting ransom demands.

They terrified her.

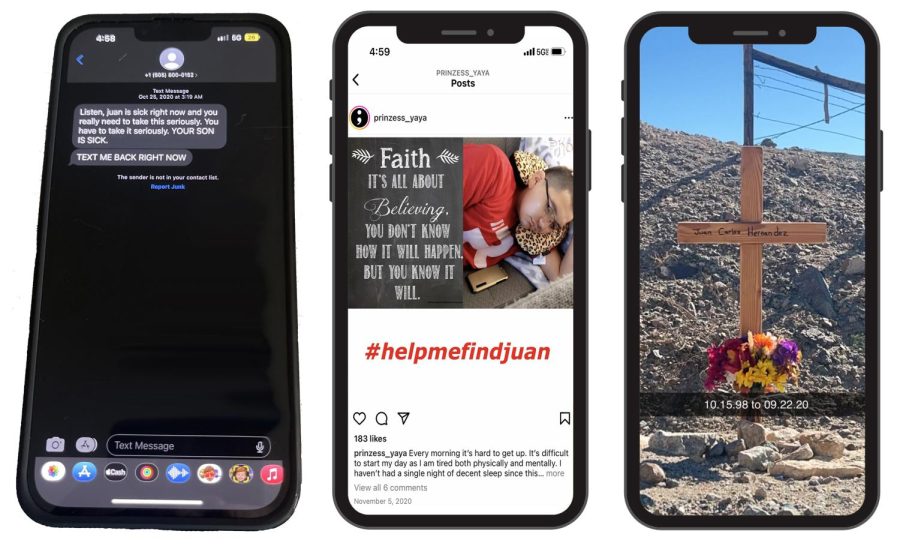

One text message said “Listen, Juan is sick right now and you really need to take this seriously…TEXT ME BACK RIGHT NOW.” Another message said they were torturing her son in Tijuana. One person threatened that they had to get the money within 30 minutes or they would cut off a finger. Another gave her 24 hours to pay or they would kill him. She panicked that her son got involved in something dangerous like trafficking for a cartel.

“I begged Juan not to work at the smoke shop because it was unlicensed,” she says.

But he told his mom that he felt responsible for helping with rent and bills. At the start of the pandemic, he was laid off from his job selling timeshares. The nation was shut down and there weren’t many jobs.

Within 48 hours of his disappearance, Yajaira Hernandez had gotten four calls and five texts, all from different people claiming they kidnapped her son. They asked for between $5,000 and $10,000.

“We didn’t have the money to pay anyone,” she says. “We live paycheck to paycheck. When I asked people to put Juan on the phone or send me a recording, no one did.”

Yajaira Hernandez says she ended every call and text the same way.

“If you do have my son let him know I love him,” she says.

At the same time, dozens of supporters were calling the LAPD to file a missing person report, and the pressure worked. Yajaira Hernandez finally heard from an officer who told her that her son’s disappearance sounded like “foul play.” He promised he would push the missing person unit to investigate.

“That was the first time I felt heard by the LAPD,” she says.

A friend connected Yajaira Hernandez to a retired detective. He told her to tell the LAPD about the ransom demands.

The LAPD immediately said she shouldn’t have posted anything on social media. She shouldn’t have put her number on any flyer.

“That made me feel like crap,” she says. “Like maybe I put my son in this position.”

But in the end, it was the ransom threats that moved an investigation forward.

In less than 24 hours, LAPD’s Robbery and Homicide Division contacted her.

“It was not missing persons or homicide that called,” Yajaira Hernandez says. “The LAPD cared more about the extortion for money than Juan’s disappearance.”

Five days after her son’s disappearance, Yajaira Hernandez met with LAPD robbery detectives Jaramillo and Jennifer Hammer. She showed them the ransom threats, but she also shared her suspicions about the dispensary. She didn’t hear back from them until two weeks later. They said they were investigating.

“By then we were doing our own thing,” she says.

She and her sons continued to post messages to social media urging people to share any information they had.

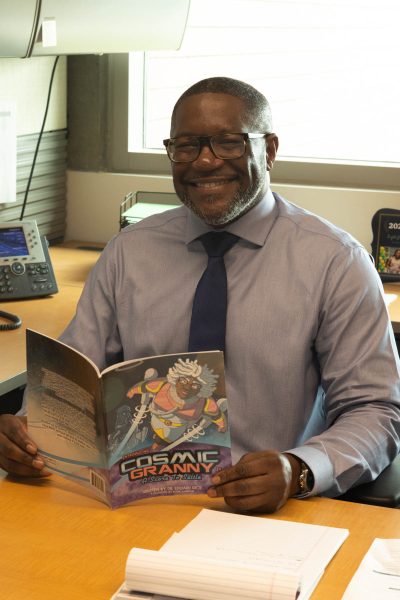

Before her son went missing, Yajaira Hernandez posted a few times a month on Instagram – a comical message about falling off the toilet during an earthquake, photos from a birthday dinner with a friend, a one-chip challenge and lots of cat memes. She had been on Instagram since 2012 and had a small following of friends and family. Her posts rarely generated more than twenty likes.

After her son’s disappearance, she posted several desperate messages on Instagram and Facebook every day urging people to “#helpmefindJuan.” She started getting thousands of views on videos, and hundreds of likes on regular posts.

“I know I may be overwhelming everyone with my posts,” she wrote on September 25, 2020. “Unfortunately, this is all I can do to spread the word on my baby boy.”

On Sept. 27, 2020, KVEA-TV broadcast a story about the search, as well as a follow-up story covering a vigil the family organized on Sept. 28, 2020.

The family also made 10,000 flyers.

From Sept. 23, 2020 to Nov. 18, 2020, hundreds of people came out every day to search the streets, parks and tent encampments.

They followed-up on every tip from downtown L.A. to San Pedro. They attached flyers to thousands of light poles and talked to everyone they saw. They organized a rally at LAPD headquarters.

Yajaira Hernandez credits everyone’s actions as “making the difference” in getting the LAPD to investigate.

“I’m very grateful for the community,” she says. “I wouldn’t have been able to do this alone.”

L.A. City Councilmember Herb Wesson donated an additional 30,000 flyers. Lamar Advertising Company only charged $900 for 13 billboards that were up for six weeks – a fraction of the usual cost. A Go Fund Me raised thousands of dollars for gas, flyers, shirts and posters.

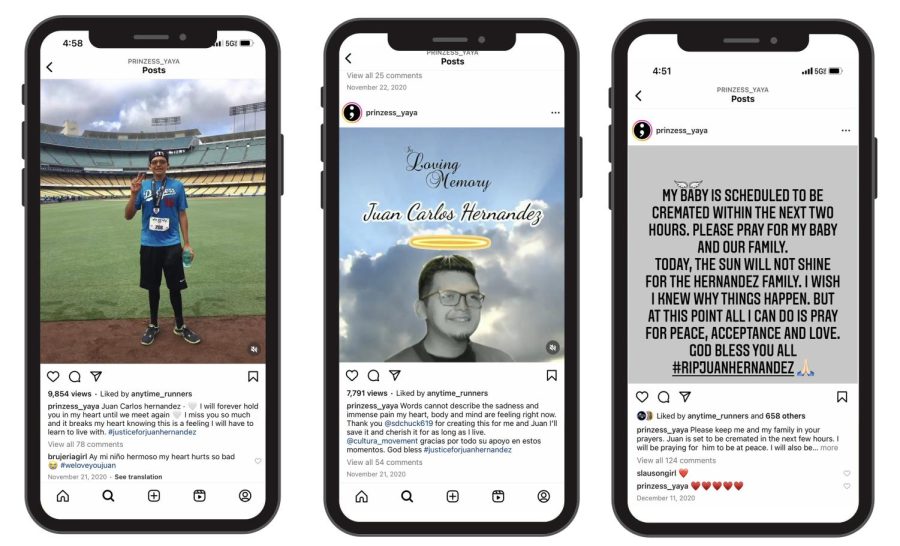

Nearly two months after Juan Hernandez’s disappearance, Jaramillo met with Yajaira Hernandez. He told her that the LAPD had worked with the San Bernardino Sheriff’s Department to uncover her son’s remains in the desert.

Hammer later testified at Astaphan’s preliminary hearing that the LAPD used cell tower data to track the movement of Astaphan’s and Peng’s phones, eventually leading them to the body.

“Part of me was relieved that Juan was found. But knowing he was dead shattered my world,” Yajaira Hernandez says.

The LAPD told her that they had arrested Astaphan and Heng. They were still looking for Peng.

“I asked if I could see Juan, but they preferred not,” she says.

His body was badly decomposed and also impacted by animals scavenging for food, the LAPD told her. It was another month before his body was released and cremated.

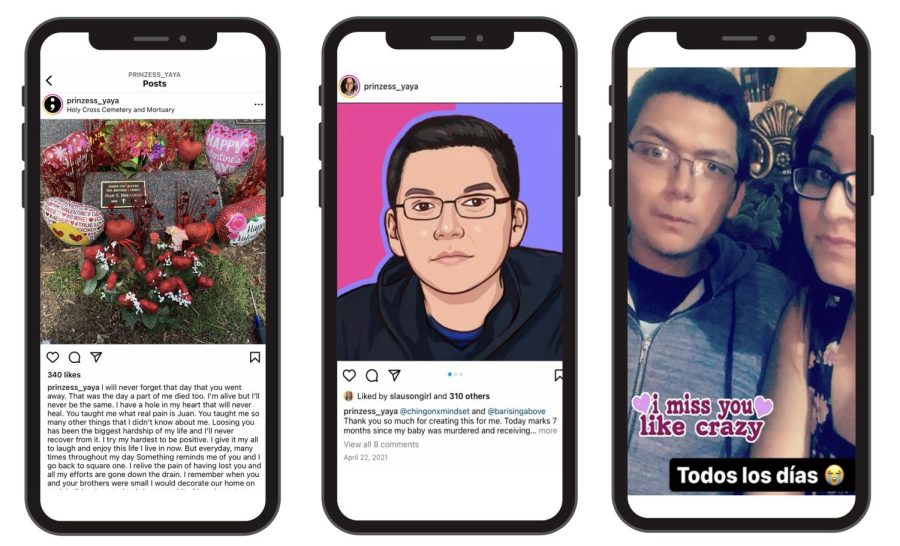

She and her sons chose a spot for his remains in the garden at Holy Cross Cemetery in Culver City.

Juan Hernandez was one of more than 500,000 people reported missing in the United States in 2020.

According to federal statistics, Los Angeles has the highest number of missing person cases when compared with other U.S. cities. LAPD missing person investigations can be requested and tracked online, although only a fraction of the people reported missing are included.

The California Department of Justice (DOJ) releases annual information on missing persons as reported by law enforcement, and the state’s active missing person cases average about 20,000 on any given day. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) shares similar data for cases it is investigating across the nation.

This is a fraction of the people who actually disappear that no one notices, or who aren’t reported missing.

California state DOJ policy states that “there is NO waiting period for reporting a person missing. All California police and sheriffs’ departments must accept any report, including a report by telephone, of a missing person, including runaways, without delay and will give priority to the handling of the report.”

However, the DOJ only collects data on people reported missing by local law enforcement, and while detailed data and resources exist for missing children, the state has little data on missing people over the age of 18.

Each year, L.A. County buries in a mass grave the cremated remains of over 1,500 people whose identities are either unknown and/or whose bodies are unclaimed by their families. The county holds individuals’ remains for three years to allow family members and loved ones a chance to claim them. In December 2022, L.A. buried the remains of 1,624 people who died in 2019.

“The LAPD made me feel like my son was nobody, like he wasn’t valuable enough to look for. This added so much to the pain and anxiety I was going through,” Yajaira Hernandez says. “We do the heavy work and they [the police] come and sweep up after us.”

Jaramillo and Balian both told Warrior Life that the persistence of Yajaira Hernandez was the key factor in forcing the start of an investigation and moving it forward.

Had she given up hope or been too intimidated to push the system, Juan Hernandez would still be missing.

The healer

As a young mom, Yajaira Hernandez, now 43, married Jose Hernandez, the father of her youngest son Gabriel Hernandez. He adopted Juan and Joseph and the boys were given the Hernandez name.

Yajaira Hernandez went to school full time and worked part time. She earned an associate degree in liberal arts. She started working at the L.A. County Department of Public Social Services (DPSS).

She and her husband separated, but remained good friends.

She was active in her sons’ lives, involving them in sports, science and robotics camps, and programs that contributed to their academics.

The Hernandez home just before the end-of-the year holidays in 2022, reflected the love that Yajaira Hernandez has for Tim Burton’s “The Nightmare Before Christmas,” including a tree decorated with ornaments depicting all the characters. Inspirational sayings covered the walls of each room, such as “Family, where life begins.”

On Yajaira Hernandez’s right arm is a tattoo with her three sons. Juan Hernandez has a halo and “Til’ I see you again,” written above his head.

After her son’s murder, Yajaira Hernandez took a leave of absence from work.

“I can’t really say my job was supportive, but thankfully, I had a job when I came back,” she says.

On Dec. 21, 2020, the remains of Juan Hernandez were buried at Holy Cross Cemetery in Culver City. Yajaira Hernandez was back at work on Jan. 4, 2021.

The mortuary had only two dates available – Dec. 19, 2020, which is Yajaira Hernandez’s mom’s birthday or her own birthday on Dec. 21, 2020.

“Life never really stops knocking you down,” Yajaira Hernandez says.

Since her son’s murder, the changes in her life are numerous.

“I sleep about two to three hours a night. I’m either overeating or not eating anything,” she says. “I get dressed and go to work to set an example for my sons, but a lot of times I want to quit. I’m constantly praying and watching videos of my son. One moment I’m OK and another I’m breaking down in tears. There’s a piece missing inside me.”

She thinks often of all the moments in her son’s life that she will never experience – his graduation from college, his wedding and the birth of his children.

“Everything we do as a family – every dinner, every conversation, every joke – I think about how much Cookie would have loved it,” she says.

To help herself heal, she began to heal the community.

On April 30, 2022, Yajaira Hernandez joined families impacted by violence at a candlelight vigil in South Central L.A.

“I’m here to feel supported and support others,” she says. “Some people are alone, and they turn to alcohol, drugs and the streets to deal with the pain. These are the consequences for the families left behind.”

Speaking to KABC-TV news and Warrior Life at the vigil, Yajaira Hernandez explained that community healing events are essential for her own and others’ healing.

“With other survivors, I’m open and honest. I don’t have to hide my pain. I don’t have to hide my emotions. I don’t have to fake a smile for my family or other loved ones,” she says. “This is for me. This is part of my journey.”

Oya Sherrills works at The Reverence Project, a healing center for families in Watts. She was at the vigil to honor her brother Terrell Sherrills, whose murder remains unsolved.

“L.A. needs resources for victims and survivors of crime,” she says. “Families need access to a lot more of the court and police records, as well as opportunities to tell our stories and shift the narrative. We are shut out by law enforcement and the courts.”

Sherrills says family members need healing services but also “healing conditions.”

“It’s really difficult managing grief,” Sherrills says about the struggles surviving family members endure. “You lose your job, don’t have a place to rest your head, don’t have access to substance abuse treatment and mental health when you self-medicate after tragedy strikes.”

To celebrate what would have been Juan Hernandez’s 24th birthday, his family worked with Anytime Runners and Rundalay to organize a 5-mile “Run for Cookie” in Griffith Park on Oct. 16, 2022. Yajaira Hernandez and her son used to run with the two groups.

“My biggest motivator is supporting my mom,” Joseph Hernandez says.

As a toddler, he struggled to pronounce his little brother’s middle name Carlos. It came out “Cookie,” and the nickname stuck.

“Every year, my mom tries to figure out how to cope with Juan’s birthday,” he says. “It’s a hard day. This year she thought about having a community event with something that she did with Juan, because their relationship was always through running.”

Rundalay founder Francisco Montes said he saw Juan Hernandez grow up.

“Even at a young age, Juan stepped up when we needed someone to pace a group,” Montes says, holding back tears. “It was amazing to see a 17-year-old lead 30 people without fear. He impacted a lot of people.”

The run raised more than $1,000 to support families of murder victims in L.A.

The warrior

Just past sunrise on April 26, 2022, Yajaira Hernandez arrived at Fred Roberts Park on Honduras Street just south of Vernon Avenue on the east side of South Central Los Angeles.

She leaned against a cement table covered in graffiti scratched into the paint.

“We’ve had enough,” Yajaira Hernandez says. “All this hate, all this violence needs to stop. If I can help out one family, then my son didn’t die in vain.”

Slowly, other people pulled up – mostly mothers and grandmothers – all there because their family members had been murdered in the streets, violent relationships or by law enforcement. They came to travel to Sacramento for the annual Survivors Speak conference and advocacy day at the California State Capitol.

Before boarding the charter bus for the long ride to Sacramento, Yajaira Hernandez spoke to KNBC-TV news and Warrior Life.

“Some days are good. Most days are bad,” she says. “When I’m around other victims’ families, I can speak without any regrets, without any shame, without feeling like I’m a burden to them. It’s like a safe space.”

Phillip Lester, who coordinates violence prevention programs for youth in Los Angeles, was also in Sacramento. When he was 14, Lester was shot twice, and was then shot again at 15.

“I got no services or counseling,” Lester says. “I was ejected [from the hospital] right back into the streets.”

As he stood on the Capitol steps before entering the building to speak with legislators, Lester also described how survivors go on living in the same homes and neighborhoods where their loved one was murdered without any access to counseling or peer support, let alone the ability to move.

“People need help after a traumatic situation,” Lester says. “Money must be allocated toward survivors of crime, and to the establishment of Trauma Recovery Centers run by folks like me in the communities where we come from.”

Since Survivors Speaks, Yajaira Hernandez has begun to speak out more often to the media, public officials and to the community about what’s needed to prevent violence and to help survivors seek justice.

“Every time I share Juan’s story I’m keeping his memory alive,” she says. “I hope that other families gain some courage, knowledge and resources from our experience.”

On Sept. 23, 2022, she spoke to more than 100 community residents at Los Angeles Trade-Technical College about how to push the police to fully investigate a case and report back regularly on the progress.

“I didn’t know anything about LAPD policies,” Yajaira Hernandez says to the audience.

She encourages them not to give up no matter how badly they are ignored or dismissed.

“If we don’t fight for our loved ones, no one will. The system won’t do it for us,” she says.

Reflecting on the past two years, Yajaira Hernandez says she carries a lot of pain, but no regrets. She pauses, bows her head for a moment, takes a deep breath and looks up.

“Like all my kids, I fought for Juan when he was alive,” she says. “And, when he was murdered, I did everything possible to find him and bring him home.”

Editor’s Notes:

- Tags were added on Thursday, May 18.

- First and last names were added for clarity on Sunday, June 4.

- Story was updated and photos were added on Sunday, June 18.