He was the victim of a hate crime, now he’s speaking up

EDITOR’S NOTE: THIS STORY WAS UPDATED JUNE 14 FOR CLARITY.

The video which accompanies this story can be found here.

Jordan Paige lit up a Black and Mild as he stood waiting for a bus at the corner of Wilshire and Western. His task was to transport a package full of gold, which had been frustratingly postponed, causing Jordan Paige to cancel his regular date night and take a different bus home than usual.

As he strolled along with the blunt, trying his best to beat the cold of the November day, he passed a man and a woman. The man looking him up and down flirtatiously.

Deciding to transition from cigarillo to blunt, Jordan put out one for the other and stood alone.

The man approached Jordan and at first stayed silent, catching a further glance at him. Jordan greeted the man and is met with silence.

Jordan had always been taught to give as little energy as possible in situations where he felt scared. This was one of those interactions. However, because the man was staring at him so intensely, Jordan felt the need to say, “hello, how are you?”

In the interest of staying safe, Jordan identified that the situation had begun to go awry when the man ignored his greeting, so he turned around to pay this other man no mind.

Suddenly, the man who had once been standing peacefully with a woman began verbally attacking Jordan and yelling profanities, slandering Jordan’s race and sexuality. The attacker filmed this event and claimed to be broadcasting it on Instagram live.

Jordan threw in a few one-liners. The attacker became agitated to a state of physical violence.

The attacker reached for a weapon, revealing a piece of wood shaped like a table leg. The woman the attacker was with yelled that he didn’t have to do whatever he had evidently planned to do.

“Oh you don’t think I’m going to do it,” the attacker said.

Almost immediately, a large piece of rectangular wood made contact with the left side of Jordan’s face, prolapsing his eye, fracturing his eye socket and lacerating his eyelid.

Months later, Jordan sat, smoking a blunt as he reflected on this moment.

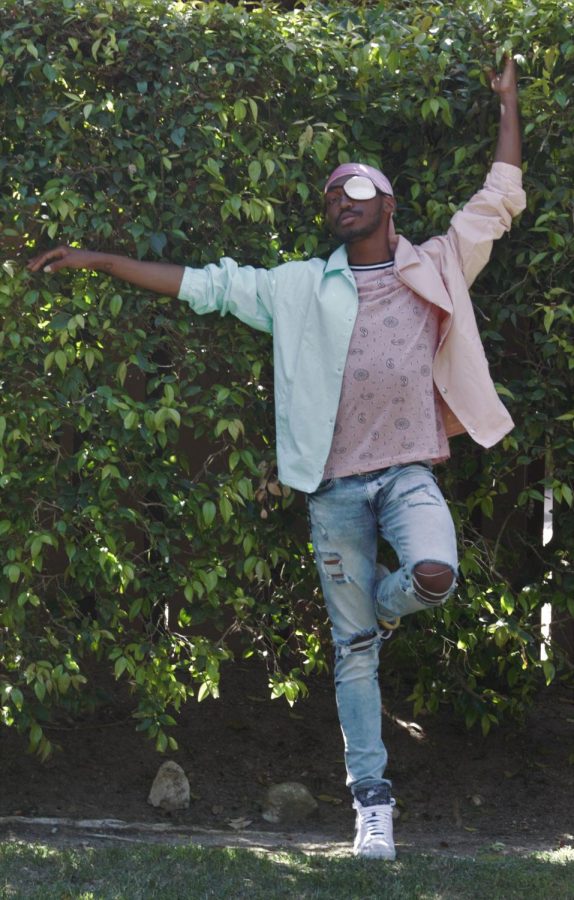

Jordan, 22, wore all pink from the waist up– pink crew neck, mauve beanie and a baby pink eyepatch stuck to his left eye. Short, tight black curls peaked out of his hat, but it covered his ears. His brown eyes creased frequently to laugh when reflecting about the odd coincidences in his life. His frame is slim, yet exudes the toughness of someone who’s had to fight through life, physically and emotionally.

He fiddled with his chin a lot, stroking the curly black wisps of hair in the shape of a beard. Jordan is well spoken, like a well-educated academic who still uses slang and jokes around a lot, especially when describing the things he loves, like drag, reading and engineering.

Shortly after the attack, Jordan lost the two jobs he’d had, putting an even larger financial burden on a student who already had to fund his own living and now had to fund his own recovery.

For the first few months after the attack, he had health insurance. However, since being laid off he’d lost his benefits for a few months right in the middle of his medical recovery process. Jordan estimated that he ended up paying around $5,000 out-of-pocket during this experience.

There were, however, a few bright spots in the grey clouds of financial dread. Jordan received money from a few Gofundmes, and has been told he will receive funding from the California Victim Compensation program (CalVCB), which his therapist referred him to.

The CalVCB program was created in the 1960’s and aims to provide aid to victims of crimes involving physical injury, the threat of physical injury or death. The maximum amount that a victim can receive from the program is $70,000, Jordan says he’s been approved to receive the maximum amount.

Those funds can be used for anything once received, but they are provided for the purposes of mental health treatment, medical and dental services, income loss, funeral and burial expenses, home security and relocation. The CalVCB exists for people who have no other means of paying off these debts.

“We’re considered the payer of last resort. And so what that means is, applicants are compensated for the covered expenses that have not been and will not be compensated from any other source,” Kimberly Keys, information officer for the CalVCB says. “And those sources include medical insurance, dental insurance, public benefit programs, like medical unemployment, auto insurance, workers compensation, and then court ordered restitution and Civil Lawsuit recoveries.”

Along with stressing over how he would pay for everything in the aftermath of his attack, Jordan also struggles from anxiety and trauma related to the attack. He’s also now half-blind indefinitely, and potentially forever.

“The healing process has been very trying. [The] recovery of the injury itself physically is basically over. I just need to, now that I have insurance again, make appointments for eye exams and possible surgery to reconstruct my eyelid itself, so that it can just look as normal as possible,” Jordan says.

According to the Los Angeles County Commission on Human Relations, in 2019 17% of hate crimes based on sexual orientation were directed toward Black people. Additionally, 39% of sexual orientation-related hate crimes occurred in a public place.

Jordan was attacked on Nov. 12, 2020 around 5:30 p.m., and statistics have not yet been released for this time period. However, Skylar Myers, Los Angeles LGBT Center client advocate, says that hate crimes were on the rise in 2020 due to the political climate and increased visibility of the LGBTQ community.

“I think that visibility and political rhetoric actually go hand in hand. You know, when we’re talking about political rhetoric, [the] binary of it, [the] us versus them thing, us looks a certain way. Typically [what’s portrayed is] a Black face, you know, running out of a store with goods or products. [That visibility] is what’s causing that hate and it’s that misrepresentation in the visibility, I think, that’s causing it to go skyrocket the way it is,” Skylar says.

While crimes like what happened to Jordan seem pointless and sickening to many, Skylar says that these crimes are appropriately named, as they’re committed by people who have hate for others who are different from them.

“It comes from an inappropriate dislike of someone for not being like you,” Skylar says.

Through homelessness, unemployment and disability, Jordan found the light at the end of the tunnel. Because of this fact, he has found a new perspective on the attack.

“After I lost my eyesight, I realized my life is a lot better than I initially gave it credit for,” Jordan says. “And the ironic thing is, even after losing my vision, I still have a better life, I still have a happy life. I have supporters, I have people who love me, who I consider my family chosen and blood otherwise.”

Despite losing his jobs and having to take a semester off from taking classes to recover, Jordan began to heal himself through the drag performing community.

Jordan still considers himself a “drag baby” despite being in the scene for a while, because he feels like he hasn’t done enough rehearsals and shows.

“I had always been working, always working professionally and always [trying] to build up my own career, writing, theatrically, architecturally or otherwise, that didn’t leave a lot of room for drag. However, it did leave a lot of room for drag appreciation,” Jordan says.

Jordan began his drag journey at 19, sneaking into the 21 and over clubs with his best friend Lemuel Johnson, referred to as their drag name Serena Infiniti, to eventually become a regular at a few different clubs in Los Angeles, including Lyric Hyperion and Redline Bar and Grill.

“He was one of the first people to come with me to a show, [Jordan] met a lot of people in the industry as well as I have, even to a point where he would go to shows and they would literally make him the tip collector, because he was just so cool with everyone in the cast,” Serena says.

As Jordan became more invested in the scene, he gained more connections and therefore, more credibility among the queens of LA. The role of a tip-collector at a drag performance is a position of honesty and trustworthiness, something which built Jordan’s reputation in the community over time.

“I’ve been doing drag for like six years, so you don’t let just anybody collect your money,” Hershii Licquor-Jete, Jordan’s friend and ‘drag auntie’ says. “But any time I’ve done a show and Jordan’s been there, I wouldn’t even have to ask like Jordan runs right up to me and [says], ‘I’m gonna collect your tips, you need your money.’ I’m like, ‘Oh, God, thank you so much.’ He’s always just been around.”

For Jordan, his position at friends’ shows was never about gaining any clout or money, he was just in the mix of it all and wanted to connect with those around him.

“I just did it for the appreciation and just to be around it,” Jordan says. “And the more I tip-collected, the more I made connections, the more I realized [drag] is a very possible thing for anyone to do. Anyone can get involved, anyone can appreciate it, can do it. Anyone can, you know, do anything and so I was like, ‘you know what, let me give it a shot.’”

Once Jordan began performing drag himself, Serena became his drag mother, helping him discover the industry through their learned experiences.

“The drag scene in LA is very competitive. Everyone wants to be at the top of the food chain,” Serena says. “Everyone wants to be at the top. Everyone’s kind of like, ‘look at me, I’m here.’ ‘I have this new outfit,’ or ‘I’m doing this new song’ or whatever. It’s kind of like, I don’t wanna say Hunger Games, but that’s kind of what it is.”

As time went on, Jordan’s two jobs, along with college classes became too much for him to dedicate adequate time and energy to improving his drag.

“Drag is all about really finding that piece of who you are, as an artist, and really putting that out there on display. No matter who sees, no matter who cares, you are the queen, you are it, you are the icon, you have to be that energy,” Jordan says.

Being attacked had one single silver lining for Jordan, a rekindled passion that had gotten away from him some time ago was now at his reach.

“It was actually being attacked, and losing my eyesight that rekindled my love for actually doing drag. I always appreciated drag. I’ve always loved drag as a contributor as a supporter, but actually being a drag queen, something completely different,” Jordan says.

Highlighting his injury, Jordan’s drag name is now Cyclops. In true camp fashion, he intends to be bold. He intends to make the audience confront his disability and why his disability makes them uncomfortable.

“I’m just now starting to figure out my voice in drag because of how much trauma I’ve gone through. [As] unfortunate as it is, it’s still kind of fortunate for me to actually be able to know what I want to do now. So I feel like going forward, I’m just going to want to perform more and make statement pieces, political statements, and wherever it goes from there,” Jordan says.

More so than a drag queen or an engineer or a student, Jordan is an advocate– but not by choice.

“I feel like I have to be [open] because if I’m not, then I don’t think anyone else would ever know. There’s so many people [who have been attacked], there’s so many stories about so many people, but not many of them actually speaking out for themselves. [A lot] of people want to stay focused on themselves, which is accurate and fine, because as a victim, you have the right to focus on yourself and everything that you need to do to survive,” Jordan says. “And I want to make sure that if I am the only person, other people know that this [could potentially] happen to other people. And if I’m not the only person, this brings a light to a bigger story, a bigger, necessary part of our life that everyone needs to [acknowledge].”

EDITOR’S NOTE: Repeating paragraphs error and a grammar mistake were fixed July 26.