My life as an oyster: Searching for gender identity

As a little kid, I wanted to be a boy. I mean, I was fully committed.

The first time I got suspended from school was in preschool, because for a week I refused to sit down when I went to the bathroom. We all had to line up to pee at the same times every day. So, everyone saw this conflict between me and the school staff play out.

Finally, the teachers got fed up and told me that I had to sit down because I “didn’t have a penis.”

“I’m growing one,” I said.

My mom was called to pick me up immediately.

By the time I was in elementary school, I invented a different boy persona every week from all over the world, wrongly and embarrassingly appropriating many cultures.

I ran around the neighborhood as a warrior in my underwear with dish towels stuck into the front and back of my waistband, shirt and shoes off, with war paint applied to my face and chest with my mom’s lipstick.

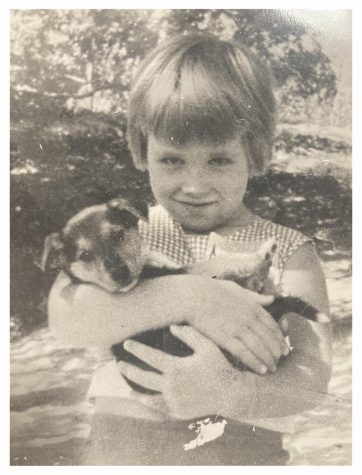

I refused to answer my mom unless she called me by that week’s name – Pedro from Mexico, Sean from Ireland, Tino from Tahiti. As Hans from Switzerland, my dog and I laid in the ice plants on the hillside overlooking the freeway pretending to herd our sheep.

I played Tom Sawyer with a friend who was female. We were Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn, and we made her little brother dress up as Becky Thatcher. I don’t remember exactly how their parents reacted, but I remember the tension.

Our creativity was not appreciated.

I credit my mom for never making me feel unwelcome or strange.

She went along with all my playing at different gender roles. She took me to get my hair cut short. She never forced me to wear dresses, although I could tell she was disappointed in how I looked and dressed.

On Christmas mornings, my mom made sure I had Hot Wheels, a G.I. Joe, superhero action figures and a toy machine gun that made the coolest sound until I filled it with sand.

I often wish I had asked her before she died, “What was it like having such a strange little kid?”

I wonder about the battles she must have fought behind my back, or the way she defended my decisions despite what she might have wished for me.

Listening to Dodger games on the radio was something I loved doing with my mom. I was a “bat boy” for community baseball leagues and girls’ softball teams, and my mom took me to the games regularly. I think she saw how much I loved it.

I decided that I wanted to be a professional baseball player, but one of the most memorable heartbreaks of my childhood happened when I was about 6, and my dad said I could never play for the Dodgers because I was a girl.

Not long after that, my friends who went to Catholic school were devastated that a teacher they loved was leaving because nuns couldn’t become priests. I held on to that as another example of the regular crushing of little girls’ dreams.

I noticed that I and all the other little girls had chores.

We were cooking and cleaning, ironing, making beds, doing laundry and babysitting at a very young age.

It wasn’t lost on us that our moms came home from one – sometimes two or three jobs – only to work late into the night doing everything to feed, care for and clean up after their families.

Meanwhile, we saw the boys outside playing or lounging for hours with their fathers in front of the TV. We also witnessed the lack of appreciation or criticism of our moms’ labor.

I started to think, “Why would anyone want to be a girl? Girls don’t get to do anything fun.”

Gender disappointment and discrimination increased as I got older.

In third grade, I was playing “three flies up” with the boys during recess, when a teacher snatched me angrily from the game and made me play with a group of girls jumping double Dutch.

I pouted and refused, so she sat me on the bench as a punishment. When I started to talk to a boy sitting there, she punished me further by making me lie in the dirt and cobwebs under the bench.

In middle school, I earned a spot on the boys’ football team as the place kicker, punter and one of two quarterbacks, but the other schools complained and I was removed from competition.

I don’t remember having any discussions with adults about sex, identity or development.

To my amazement, my mom was always patient and supportive, but she didn’t seem to understand or want to discuss what I was experiencing.

Even as little kids, everyone was experimenting – playing house, playing doctor and pursuing crushes. There was a huge disconnect between what we were doing and what our parents and teachers thought we were doing.

One day I was eating dinner with my family and I said a girl told me that when I got older, every time I went to the bathroom, I would bleed.

My dad always looked angry, but, that was the only time I saw him look afraid. He told my mom to deal with it and fled the table.

The next day, my mom showed me a giant, scientific text book with complicated diagrams identifying body parts. That conversation flew way over my head.

That was the first and last time that I got any sex education other than on the streets, playgrounds and backyards of my childhood.

At the start of fifth grade, I went to a school where I didn’t know anyone. I could hear the whispers and dreaded being asked about my gender. When the teacher forced us to stand at opposite sides of the room for a spelling bee, girls on one side, boys on the other, I had to choose. I never felt so alone in a crowd.

When people asked me, “Are you a boy or a girl,” I would answer, “Maybe.

By sixth grade, I was at war with my body, especially devastated by the development of my breasts. We had a concrete floor, without a rug or carpet. For months, I would lie on the floor to watch TV with my body pressed into the cold, hard floor, hoping that I could force my breasts to stop growing. I wouldn’t use a pillow, thinking that lifting my head even slightly would release the pressure of the floor against my chest.

Before leaving the house, I wrapped my breasts tightly in an ace bandage to flatten them, a practice I recently found out is both common and dangerous.

I fought with my dad always, even as a toddler. We had a mentally, emotionally and physically volatile relationship until he disappeared. I don’t remember many conversations about anything, and never about my identity, except once.

I was playing ball, and he came outside visibly angry and yelled at me in front of everyone.

“Get the f–k in this house and put on a bra.”

Not long after that, he left L.A. I never saw him again except for two very short conversations less than three minutes long, and one phone call that also lasted only a few minutes.

By high school, I had given up. I tried to be and dress like a girl to fit in. I grew out my hair. During one torturous semester, I was a cheerleader. Despite these efforts, I was much happier as I played on the boys’ high school soccer team, traveled with the boys’ varsity football and basketball teams as their statistician, and played in a men’s community softball league.

A few years later, I was living in the South Bronx.

For the first time, I knew young people who were radically stretching every societal and family definition of who they were versus who they were told they “should” be. Especially among the queer house communities in the ball scene and the numerous youth of color reclaiming the west side piers along the Manhattan riverfront, young people carved out safer and more supportive places for themselves than what they had experienced uptown and in the outer boroughs.

They began to expose their sexual exploitation at the hands of older, richer, white men and fought back against the white gay world that dominated New York City’s queer politics.

Young people made brave and ferocious pronouncements of their racial, gender and sexual identities, despite facing exile from their homes, brutal violence in schools and on the streets, and terror at the hands of the police.

Still, most families, schools and neighborhoods had no vocabulary – let alone acceptance – for gender-nonconforming, transgender, or gender-fluid people.

Then, by 2010, new courage and confidence was erupting everywhere in how people identified themselves, as well as in the ways they rejected strict gender boxes and expectations.

A sexual and gender revolution was happening.

Knowledge and discussions about transgender and nonbinary identities rapidly increased. Artists included more complex and diverse characters in films, television and music. Gender dysphoria gained wider exposure and treatment options and resources expanded, even in the most dangerous spaces for queer people, including jails and prisons.

Generations before colonization, genocide, religious fundamentalism and the forced removal of children from their communities into boarding schools, orphanages and foster care, many cultures had words, roles and acceptance of queer identities. Some indigenous nations have honored “two-spirited” people as skilled healers and religious leaders for centuries.

I wonder how different my life – and the lives of millions of others – would have been if we had just been born at a different time or place in history.

There are many who think the rejection of gender norms and expectations is sick, or contagious or dangerous, and that people are confused or “choosing” nonconformity.

But so many of us are confident at the age of three or four that the labels we were given at birth just don’t fit. We take on the whole world to demand a different life for ourselves. That confidence is what we should all look to as the ultimate and essential truth – we are born this way.

Unfortunately, for too many of us, that confidence is short-lived. In our deepest memories, we know who we are and how happy we are when we can just be ourselves, but family, religion, school and politics beat us back into a box, or worse, cause us to look toward addiction or suicide to escape.

LGBT2IQ22 (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, two-spirited, queer and questioning) youth are “four times more likely to seriously consider suicide, and to attempt suicide versus their peers” according to The Trevor Project.

For me, determining how I define myself wasn’t easy.

As people began to fully describe their identities, instead of just introducing themselves and adding pronouns to email signatures and name tags, the closest thing I could think of was that I was most like a 10-year-old boy – someone who loves cartoons and comics, loves Star Wars and superhero movies, plays too rough, loves to jump in the mud, but never wanted to soak in a mud bath.

But I rarely said it.

It didn’t seem mature, respectful or thoughtful. It wasn’t “deep” enough.

Just like that little kid that answered “maybe” when asked what I was in fifth grade, I always say now, “You can use any pronoun for me.” And I mean it. I feel comfortable being all of the above.

But I haven’t met anyone else so noncommittal.

Then, in 2019, I had the opportunity to travel to London. Before entering their public train system for the first time – the “Underground” or what Londoners also call “the tube” – I bought a Snapple.

I popped the cap, and the fact underneath said that “oysters can change from one gender to another and back again.”

“Hmmm,” I thought, “that’s interesting.”

I walked downstairs and inserted money to purchase my Underground access card. It came out of the slot and I read, in big letters, “Oyster” card.

“What? That’s crazy!” I almost said it out loud and laughed.

I took both the Snapple cap and the Underground pass as a significant sign. Since then, I have identified myself – and come to accept myself – as an oyster.