The fight started 78 years ago.

No blood was spilled.

No fists thrown.

But the debate has been brutal.

And, the conflict? It’s still not settled.

Since its start, El Camino College has searched for its identity, including its name, logo and mascot.

Early in the fall term of 1946 – before ECC’s official founding in 1947 – the student body chose “warriors” as the college mascot, and a Spanish conquistador was first used as El Camino’s symbol.

But “the question has constantly arisen,” wrote Student Body President Bob Wright in the Nov. 18, 1948 issue of the El Camino College News. “What type of warriors are we?”

Unable to make a decision, the student council used the newspaper to raise the question with the campus community. They asked student council members Margaret “Margie” Evans and Don Cadoo to present counter arguments.

“When I hear the word ‘warrior’ spoken in connection with our school as a motto, I immediately visualize a fierce, war-painted Indian who is prepared to remove the scalp of anyone who might be standing in the path of victory for himself or his tribe,” Cadoo argued. He added that the college should not be represented by a conquistador that fought under a “foreign flag.”

Evans argued that a Spanish conquistador better represented El Camino.

“Someone drew a little Indian clothed in hardly more than a loin cloth, detachable pedal-pushers and one limp feather,” Evans wrote.

She asked if future graduates imagined their diplomas with a “shivering, thinly-clad little character grinning up” at them. “If the Spanish didn’t fight, how did they conquer the Indians? Are we going to simulate the conquered or the conquerors?”

In the same issue of the paper, student Herschel Dean is credited with the alleged disappearance of the college mascot, Dusty, a burro selected to reflect the conquistador theme.

In a student body election, Cadoo’s side won, and from 1948 on, El Camino was represented by stereotypical and often racist images and terms – caricatures of Indigenous people and culture.

Today, in 2024, ECC has no official mascot.

All three of the original college symbols remain integrated into campus culture – the conquistador, Native American imagery, and a Spanish mission bell.

In the bookstore, El Camino caps are still sold with an arrowhead symbol.

Both the name of the college and the bell logo that saturates El Camino’s social media, signs, sweaters and souvenirs, represents “El Camino Real” – The King’s Road or Royal Road – an imagined 600-mile route that connects the 21 missions in California.

On the college’s original seal, a Spanish conquistador is depicted beneath a mission bell with the words “the road to knowledge.”

El Camino College’s name and various logos – rooted in decisions that were made in the 1940s – continue to uplift some people, crush others and leave many more confused.

ECC’s identity remains elusive.

“A white-washed, romanticized and distorted history”

In 1946, the Centinela Valley Union High School District, Redondo Union High School District and the El Segundo Unified School District established a new junior college to serve the South Bay.

On Sept. 19, 1946 the newly formed college board voted to name the college El Camino after El Camino Real.

At the time, the symbolism of the missions and their bells was popular in California. In an effort to draw tourism into the state, beginning in the early 1900s and continuing through the 1950s, communities throughout California erected iron bell markers. The bells commemorated their invented version of El Camino Real, a modern imagining of a pathway connecting the 21 missions in California from San Diego to Sonoma.

The mission system was built by the Catholic Church and enforced by Spanish conquistadors resulting in the colonization, enslavement and genocide of native people throughout California.

Indigenous communities challenged the mission system through escaping the mission grounds, work stoppages, and uprisings. In 1785, a medicine woman named Toypurina united 6 of the 8 the Kizh / Tongva / Gabrieleno villages across what is now Los Angeles County to rise up against Mission San Gabriel.

On the night of the rebellion, Toypurina and the other leaders were ambushed and captured.

In her trial, Toypurina said, “I hate the padres and all of you for trespassing on the land of my forefathers and despoiling our tribal domains.”

According to the National Park Service, when the Spanish founded the first mission, the Indigenous population in California was approximately 310,000, representing 64 distinct languages. During 52 years of Spanish rule from 1769 – 1821, 68% of California’s Indigenous population – 210,000 people – died due to massacres, disease, or loss of food sources through forced removal from their land.

The U.S. annexation of the southwest through an illegal war with Mexico hastened the genocide – and near extinction – of California’s original people.

In the early years of American rule during the Gold Rush, nearly 100,000 more Indigenous Californians were massacred and thousands of children kidnapped and sold into slavery.

California’s Native American Heritage Commission reported that by 1900, 96% of California’s Native people were wiped out by Spanish and American colonization.

“I didn’t know what the El Camino symbols meant. I knew warriors was our mascot, but didn’t know of ties to Indigenous people or the Catholic Church,” said Brandon Molina Berrios, part-time advisor and graduate assistant with the El Camino counseling center.

Molina Berrios is Maya Kaqchikel, one of the many Maya nations in Guatemala.

“For me, the Catholic Church had a huge role in the colonization and genocide of Indigenous people,” Molina Berrios said. “But, there are also Indigenous people who are Catholic, and use that as a method to continue their own traditions. And a lot of people use it as a survival method. That doesn’t make them any less Indigenous than people who practice ceremony.”

In 2018, the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band called for the removal of all El Camino Real bells across the state. In their campaign to successfully dismantle the bells in Santa Cruz, California, the Tribal Council issued a petition stating that the mission bells “glorify and celebrate the domination, dehumanization and erasure of Indigenous people of California” and represent a “white-washed, romanticized and distorted history.”

Both the City of Santa Cruz and the University of California at Santa Cruz removed all the bells in their communities, dismantling the last marker on Aug. 28, 2021.

“Maybe El Camino was seen as the path to knowledge,” Carla Cain, El Camino College archivist, said.

“You have the conquistadors and the monks establishing the missions, but you also want to identify with an Indian brave? It was all kind of a mish-mosh. It wasn’t really researched. It was a mess,” she added.

“The warriors had on their war paint as they scalped a band of renegades.”

This investigation began with a search of the Schauerman Library’s El Camino College archives including a UCLA doctoral thesis on the founding and early history of the college published in 1971 and sports pressbooks from 1950 to 1980; available ECC Board of Trustee meeting agendas and minutes from 2016 to 2023 on www.boarddocs.com; and the ECC Journalism Department Student Media Archives including scanning through 1,548 issues of the school newspaper from 1947 to 2012, nine issues of Warrior Life Magazine from 1963 to 1967; and the college yearbooks published between 1947 and 1962.

Several facts emerge.

The initial debate on the college’s logo and mascot excluded many people on campus and in the community.

Wright, Evans and Cadoo were white, as was the rest of the student leadership in 1948.

There is no evidence that anyone criticized their arguments or their rights as white people to debate the use of a conquistador versus an American Indian warrior as the school’s mascot.

The guidance, experiences and opinions of Indigenous rights groups and tribal leaders were absent from the documents and college media coverage searched, despite the existence at the time of numerous local and national tribal governments and Indigenous rights organizations.

The National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) was founded in 1944 and established at its first Constitutional Convention that one of its core purposes was to “protect American Indian and Alaska Native traditional, cultural, and religious rights.”

In the 1940s and 50s, “the college was 99.9% white,” Cain said. “Nobody thought anything about it, or expressed an issue with it.”

Once the “American Indian warrior” theme was selected, it was reflected frequently on the pages of student publications, as well as in student activities and sports.

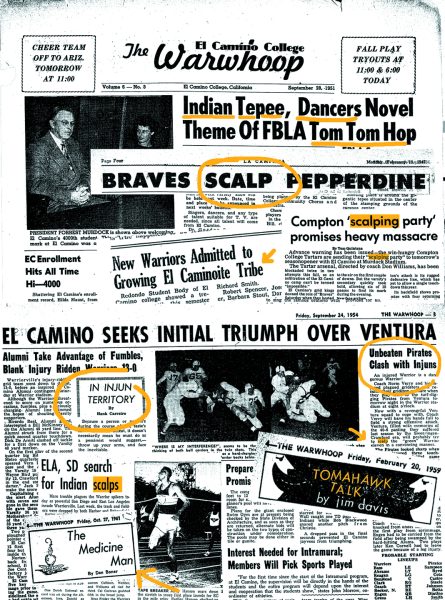

Between 1946 and 1948, the newspaper went through six name changes – El Camino College News, La Campana (TheBell), Warwhoop (with a hand-drawn masthead and mimeographed copies), El Camino Press, The War Whoop and The Warwhoop. The Warwhoop remained as the newspaper’s name until 1997.

On Nov. 4, 1948, a reference in The Warwhoop is made to “Dusty the Burro” making his debut as El Camino’s mascot at a football game where he pulled a cart full of cheerleaders across the field. But the donkey was allegedly kidnapped as the conquistador theme was dropped and never appeared as the mascot again.

On April 27, 1956, the Warwhoop published an article as to Dusty’s fate: “Sports in Warriorville had a distinctly rustic odor with Dusty, a burro, acting as team mascot in the early days… In 1947, a big issue was whether the EC Warrior was to be a Spanish or an Indian. A student body election was held, and the Indian won the day… From that date, the Indian motif has predominated in college activities.”

White students filled Warwhoop pages dancing at a “Tom Tom Hop,” decorating functions with teepees and dressing in fake feathered headdresses.

The terms “scalp” or “scalped” referencing the violent detaching of a person’s hair and skin from their skull appear at least 77 times in the newspaper in both sports and news coverage over more than 40 years.

On October 20, 1950, the Warwhoop reported that “A capacity throng of more than 7,000 packed Griffith Stadium to watch an old-fashioned cowboy and injun battle. The Warriors had on their war paint as they scalped a band of Renegades 27-7.”

A few additional examples include: 1947 – Braves scalp Pepperdine; 1954 – Unbeaten Pirates clash with Injuns, a vengeful Ventura squad will probably try to scalp the green Warrior eleven; 1954 – San Diego’s scalps most certainly feel loose these days; 1959 – Indians invade border city (San Diego) in hopes of scalping Knights; 1963 – Compton scalping party, the win-hungry Compton College Tartars are sending their scalping party to tomorrow’s season opener with El Camino; 1987 – Fullerton College scalped the Warriors; and 1989 – …were scalped three times by the Warriors.

Referring to scalping as a traditional practice among Indigenous warriors is a familiar American stereotype. Scalping was actually introduced by the English and French colonies in North America that paid bounties on the murder of Indigenous people. Carrying bodies back as proof was impossible, and scalps were encouraged as proof of a kill.

The names of the Warwhoop’s ongoing editorial and sports columns also reflected stereotypical American Indian references including In Injun Territory, Tomahawk Talk, The Medicine Man, On the Warpath and Smoke Signals.

Various yearbook covers included illustrations with an American Indian Warrior, feathers and The ECC bell.

The sports press books published by ECC’s Athletic Department from 1972 to 1975 had offensive caricatures of American Indian warriors.

“They were a product of their time.”

Several people interviewed and surveyed on campus felt that questioning the actions of people in the past is unfair.

They asserted that the students, faculty and/or administrators who chose to name the college El Camino, the newspaper Warwhoop, and who adopted the symbols were reflecting the time in which they lived.

They further argued that their innocence and ignorance is understandable, and that they weren’t aware of the centuries-long history of human rights violations against Indigenous people and other oppressed groups.

But, Torrance and the surrounding cities that made up El Camino’s demographics in the decades preceding and following the college’s founding witnessed – and sometimes directly experienced and participated in – significant discrimination against many marginalized communities in Southern California, the U.S. and internationally.

World War II had just ended – the deadliest war in history with 50 to 85 million fatalities, the brutalities of the Nazi holocaust and the devastating destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Between 1942 and 1945, at least 120,000 Japanese Americans across the U.S. were removed from their communities by the federal government into incarceration camps. Torrance had one of the nation’s largest Japanese American populations, and 10% of Torrance’s population disappeared, their bank accounts and property confiscated.

In 1943, sailors docked at San Pedro roamed the streets of South Bay cities and Los Angeles beating mostly Latino, but also Filipino and Black youth in what was called the “Zoot Suit Riot” but is more accurately a “military riot.”

Throughout the South Bay, women filled the munitions plants as men joined the military, and then struggled against expectations that they would return to traditional “female” roles at home when the men returned from WWII.

From 1920 until the 1970s, more than six million African Americans fled the brutality of Jim Crow segregation and racist violence in the southeastern United States. U.S. Census data documents that the Black population in Los Angeles rose from 63,700 in 1940 to 763,000 in 1970. Blacks who came seeking opportunity and safety instead faced police brutality, racist housing covenants, redlining, segregated neighborhoods and schools throughout L.A. County.

Inglewood – along with Glendale and Burbank – were “sundown towns” that used threats of violence and arrest to ban Black and Brown people from their cities after dark.

El Camino College, Alondra Park and Alondra Park Golf Course were built on land where local officials illegally blocked the establishment of Gordon Manor, the planned construction of a middle class Black community.

“Our [ECC’s] creation aided in the displacement of African Americans from Southern California. We have to work on acceptance,” Roshumba Mason, El Camino child psychology major, student staff at the Black Student Success Center and founder of the Mommy Scholars project to support pregnant and parenting students, said. “It’s a large space that would have been a pretty large African American community in Torrance. They weren’t gonna let that happen.”

In addition, ECC might have had many more people of color on campus if federal authorities, education leaders and bank administrators hadn’t barred Black, Brown and Indigenous WWII veterans from accessing G.I. benefits to access higher education, loans and housing.

Given the historical evidence, it’s hard to argue that El Camino students were unaware of racial discrimination or the demands of communities of color for protection, redress and repair.

In addition, for decades, future generations of students, staff, faculty and administrators continued to defend and maintain these original decisions despite active criticism both on and off campus.

On the front page of the March 5, 1998 issue of The Union, Harold Tyler, El Camino director of student development acknowledged that the college had received pressure for decades to change the mascot and other use of Indigenous images, names and symbols.

“In the 60s and 70s, the Native American Club [on campus] was very active and was against the Indian image and the [newspaper] name Warwhoop too,” Tyler said. “Many groups had been demanding that we and other places change their names.”

Overlooking past prejudice and discrimination based on people being a product of their time, also erases the actions of everyone who challenged injustice while living in that exact same time.

As the campus debated the use of stereotypical names and images, the front page of the Dec. 4, 1997 issue of Warwhoop, – the last newspaper under the name of Warwhoop in the El Camino archives – featured Mexica dancers from Mexico City performing a sacred ceremony on campus as part of ECC’s “Native American Week.”

For Molina Berrios, the struggle for Indigenous rights is not history, it is ongoing.

His father is a refugee who fled the Guatemalan civil war that occurred from 1960 – 1996, during which government forces killed or disappeared more than 200,000 people, 83% of them Indigenous Maya.

“There’s generational traumas you can see within our family,” he said. “He [my father] was very wary of me being a student activist in college because of what he saw in our homeland – taking of our land, taking natural resources, committing violent acts against native people.”

Molina Berrios was a student activist at Harbor College and UC Riverside where he fought for Native student representation and retention.

“Us as Indigenous people, we see the world differently. We want to protect Mother Earth. We want to sustain our homelands. But obviously, governments have different views of that,” he said.

“It’s hard to be an Indian.”

In July of 1968, the American Indian Movement (AIM) was founded in Minneapolis and quickly grew to address issues for Indigenous people living in urban areas and on reservations.

In 1969 AIM supported allies in San Francisco – United Indians of all Tribes and the Alcatraz Red Power Movement – in occupying Alcatraz Island for 19 months and demanding that federal land be returned to Native Nations. In 1971, AIM members took over the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) headquarters in Washington DC to protest brutality and neglect against Indigenous people by reservation police and BIA officials.

AIM members also offered protection to communities impacted by BIA tribal police and FBI violence against “traditional” Indians who were working to bring back spiritual and cultural practices that the U.S. federal government had outlawed in the 1800s. These efforts included the 1973 AIM standoff with the FBI at Wounded Knee on the Oglala Lakota Pine Ridge Indian Reservation.

Indigenous youth throughout the U.S. were inspired to take action at the local level. On May 20, 1977, the South Bay Daily Breeze reported that El Camino College’s American Indian Club was demanding that The Warwhoop change its name.

AIM founder Dennis Banks traveled to El Camino on the first day of the election and spoke before hundreds of students, urging them to vote in favor of a name change. Several published letters to the Warwhoop editor backed the American Indian Club.

Despite these efforts, changing the Warwhoop name was again voted down on campus by a narrow margin of 17 votes.

Dave Bowman, student editor of The Warwhoop at the time, told the Daily Breeze that “of course we defended the name of the paper in our editorials.”

Student editors wrote about The Warwhoop name that “It’s not a putdown of the Indian culture. It’s held a positive image for years, especially in the student journalism field. We would not support any name which we thought might be distasteful, injurious or inappropriate.”

The Easy Reader in Hermosa Beach also covered the issue with the headline, “ECC students decide to Whoop it up.”

Easy Reader reporter Dave Hunt interviewed Banks who said “Warwhoop always has negative connotations when used by whites.”

Hunt also reported that Banks told students on ECC’s campus, “The frontier mentality still exists. We need to sensitize non-Indian officials to the problems we face. It’s hard to be an Indian.”

Twenty years later, in the fall semester of 1997, ECC again debated the Warrior mascot.

At the time, the Los Angeles Unified School District had just passed a resolution ordering the elimination of team names and mascots referencing Native American people and cultures.

That move sparked similar conversations on El Camino’s campus.

On Oct. 16, 1997, The Warwhoop reported that in the previous month’s Associated Student Organization elections, El Camino students voted to “remove Native American references from campus,” including removing the arrowhead symbol from sports uniforms.

The name “Warriors” would continue.

Gene Engle, football team offensive coordinator, blamed the name change on people being “politically correct rather than taking into full account everybody’s feelings.”

To this day, ECC Football’s social media accounts on Instagram and X retain the arrowhead logo. The arrowhead still decorates El Camino football helmets.

“We did have the warrior emblem on the P.E. Department… a warrior Indian with a bow and arrow. Who took it or where, I don’t know.”

Jimmy Macareno, one of the Division of Facilities Planning and Services’ two painters, started at El Camino in August of 1979.

He doesn’t remember the college having a logo at that time. “We did have the warrior emblem on the P.E. Department,” he said. “It was a warrior Indian with a bow and arrow.”

On Jan. 30, 1997, The Warwhoop published a photo of the 1959 installation of a 12-foot, aluminum statue of a man with a mohawk, wearing a breechcloth and shooting an arrow that hung on the North Physical Education Building since it was installed.

Later that same year, The Warwhoop ran another photo of the statue’s installation. The caption read, “After more than 50 years of tradition, EC may be changing the look of the Warrior mascot due to outside pressures from Native American groups.”

Not long after, El Camino students voted for the mascot change, and the statue disappeared.

“Who took it or where, I don’t know,” Macareno said.

He hasn’t heard anything about it being in storage somewhere on campus. “Then again, I didn’t dig into it. People wanted to know what happened to it about eight years ago” and were “trying to find it,” he added.

Macareno isn’t sure that a warrior mascot best represents El Camino. “If it’s too sensitive, I’d say get away from the word, period. Not use warrior,” he said.

The NCAI developed a National School Mascot Tracking Database of more than two dozen different Native “themed” school mascots used by K-12 schools. The Database also reports on progress in eliminating Indigenous-themed mascots.

As of April, 2023, “warriors” was used by at least 236 school districts and 406 school districts across the country.

“1998 will be a true beginning of this college’s next 50 years – years of dialogue and diversity – with the students’ publication leading the way.”

The change in the mascot renewed concerns on campus about the newspaper’s name.

On Oct. 23, 1997, The Warwhoop reported on its front page that the student “vote to change mascot makes name of paper questionable.”

Jolene Combs, journalism professor and faculty advisor to the newspaper, was quoted as saying “Warwhoop refers to certain American Indian tribes who, after a successful scalping of a foe during a battle, would let out a victorious shout or “whoop” to celebrate their accomplishment.

This inaccurate depiction was repeated by student editors in the Warwhoop as an argument against changing the paper’s name.

The NCAI, the American Indian College Fund and other Indigenous rights organizations had asserted for decades that references to scalping, tomahawk chops, war whoops, fake Indian dances and accents were offensive and inaccurate Hollywood portrayals of Native American culture.

Stefanie Frith, then student news editor, said “Changing the name of the paper will be hard because it is a big part of the college. But as much as I would like to see the newspaper’s name stay, I realize that in order not to offend anyone once the college changes its mascot, our name has to go.”

“I don’t think we should be appeasing the few people who complain,” Jaimie Calhoun, assistant editor, said in the Warwhoop on Dec. 4, 1997. “I think it’s sad that people are so thin-skinned.”

Frith added, “Yes the name is derogatory to Native Americans. But this name has been around for 50 years. I’m sad to see it go.”

In that same article, campus and community news editor Angela Woods said changing the name was the “right thing to do,” for everyone involved, not just those who expressed concerns.

On Nov. 20, 1997, The Warwhoop ran an editorial. “Changing the name is in good faith. The name of the newspaper is derogatory and implies violence and relates poorly to the diversity of the college… We expect that 1998 will be a true beginning of this college’s next 50 years – years of dialogue and diversity – with the students’ publication leading the way.

On Feb. 12, students published the first issue of the newspaper under The Union.

In 2005, the American Psychological Association (APA) published a resolution “recommending retirement of American Indian mascots, symbols, images and personalities by schools, colleges, universities, athletic teams and organizations.

The APA argued that “symbols, images and mascots teach non-Indian children that it’s acceptable to participate in culturally abusive behavior and perpetuate inaccurate misconceptions about American Indian culture,” as well as create an “unwelcome and often times hostile learning environment for American Indian students that affirms negative images/stereotypes that are promoted in mainstream society.”

Martin Leyva, full-time sociology professor at El Camino College specializing in criminology, warned against cultural appropriation in the selection of educational and sports identities.

“It’s really important for El Camino to know history, especially as we talk about being inclusive,” Leyva said. “We need to understand peoples’ cultures, so we’re not pressing harm on anybody, even if it’s just a word or a symbol.”

“The warrior code is taught from the start. That code means everything, because it’s what keeps us alive in country.”

Since he was 11-years-old growing up in Carson, Jovanni Soto wanted to be a soldier. He participated in a military cadet program.

“I thought it was cool and I also wanted to be of service to the country,” Soto said.

In 2003, he enlisted in the Marine Corps.

He was deployed to Iraq where he worked in aviation electronics. Even though he wasn’t directly involved in combat, he and his fellow Marines took on regular mortar fire and lived with the constant fear that life was not promised.

Now two decades later, Soto is attending El Camino and serves as a student worker at ECC’s Veterans Resource Center.

He is surrounded by students half his age in “Warriors” gear who have never been in a battle.

Like the absence of Indigenous voices, the voices of the actual warriors on campus have also been left out of the debate on El Camino’s warrior identity.

In the 1940s when El Camino was founded, many students were soldiers returning home from World War II or women who had worked in munitions and other South Bay factories fueling the Allied forces. Students attended classes in converted army barracks.

On Dec. 7, 1948, The Warwhoop noted that 500 students – 25% out of a total ECC population of 2,012 – were military veterans. But, nothing could be found in the ECC archives highlighting their involvement or opinions in the selection of the college’s name, logo or mascot.

Soto said he came home from Iraq strong physically but mentally fractured.

He doesn’t agree that the U.S. should have gone to war against Iraq. He said there was no evidence that Iraq was involved in 9/11.

“But, for anybody that’s been in any theater or any conflict, it’s hard to question the cause,” he said.

He focused on the job in front of him each day. “Even though I’m tired, there’s people out there who need air support as quickly as possible.”

“Getting out of the military and assimilating back into civilian life is very difficult,” Soto said. “In the military, you get a lot of support. You have your brothers and sisters in arms right beside you – that security blanket – three square meals a day, a roof over your head, you’re provided equipment, uniforms. You leave as a kid and you come out like what am I going to do?”

For years, he was lost in his head, depressed and drinking heavily.

His family was more concerned about his safety now that he was back in Southern California than when he was in Iraq. “They often worried if I’m gonna come home, and if I do, will I be in one piece,” Soto said.

Soto was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, but it took him years to seek help.

According to Soto, the values of a warrior include honor, courage, commitment, integrity and dependability.

“In the Marines, the warrior code is taught from the start,” Soto said. “That code means everything, because it’s what keeps us alive.”

He feels proud of El Camino’s Warrior name, but also said there needs to be an open forum open to everyone on campus to discuss the college’s mascot.

“I do still consider myself a warrior, Soto said. “Even though I’m done with fighting in that war, I’m fighting my own war – improving my life, keeping my sanity and helping other veterans.”

Across from the Veterans Resource Center in the Communications Building, Francisco Lopez works with students who are attending college after decades of incarceration.

As coordinator of El Camino’s Formerly Incarcerated Students Thriving (FIRST) Program, Lopez speaks regularly with people who have suffered violence on the streets and within California’s prisons and jails, students who have often been expected to serve as soldiers in a conflict that predates their birth.

“Growing up, this thing about being down for your homies, for your community is the most ultimate valued thing,” Lopez said. “If someone is disrespecting your homie, or somebody is jumping them, as a warrior you have to go and back them up, even if that means getting into trouble for the people you care about.”

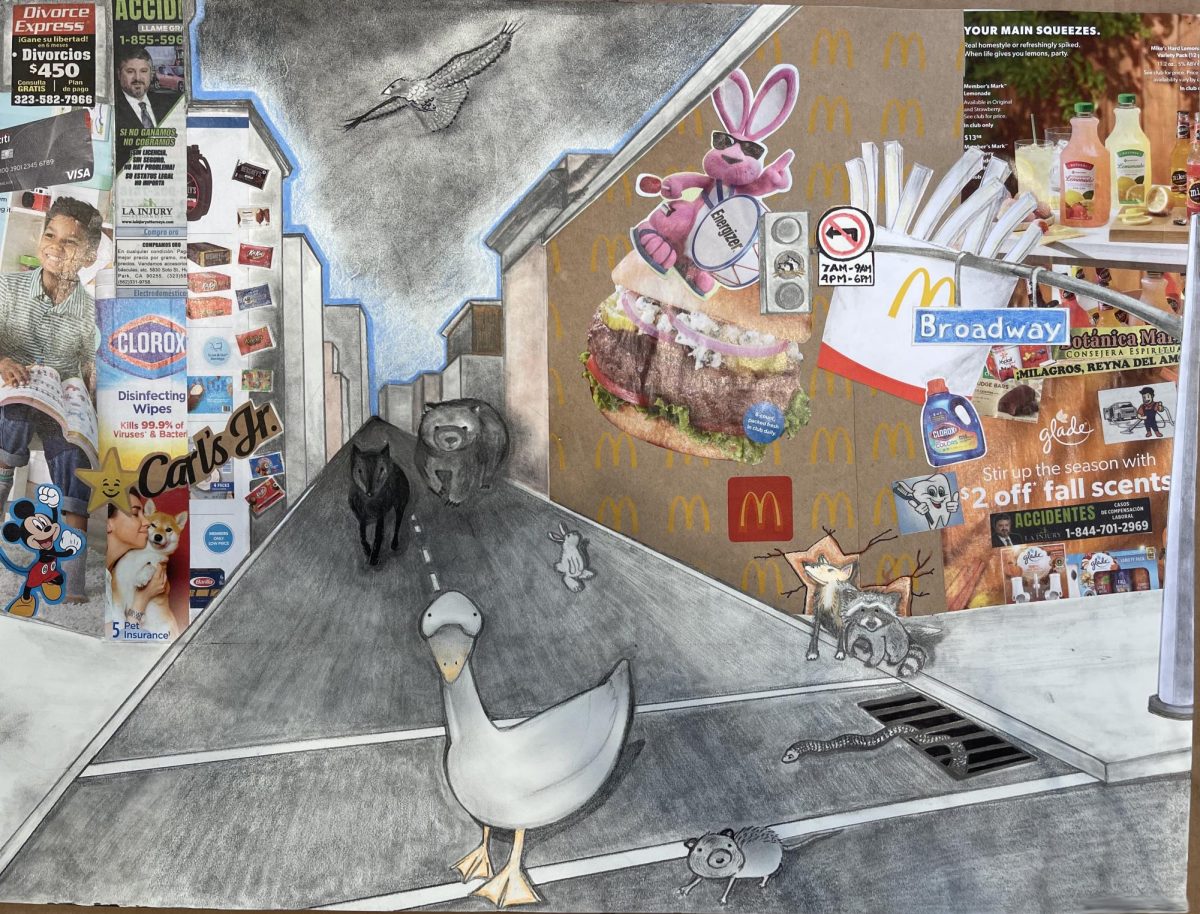

Lopez embraced the graffiti culture in the 90s and early 2000s. The majority of people that were tagging “illegally,” Lopez said, were people of color because they didn’t have access to “legal” walls or permission.

“This concept of a war on a culture – graffiti culture, gangbanging culture, low-rider culture – it impacts communities that are more vulnerable,” Lopez said. “I learned what a warrior meant based on what my relatives did – taking care of your loved ones, sacrificing your well-being to make sure that the people you love are being taken care of.”

Both Soto and Lopez exist on a campus with a schizophrenic warrior identity championed by students, staff and faculty most of whom have never experienced war.

“Being a fan of El Camino students because they’re so great, I would say they’re warriors against backwardness, prejudice and discrimination.”

One of the places on campus where people are encouraged to discuss identity is El Camino’s Social Justice Center (SJC) located on the first floor of the Communications Building.

“People think of the stereotypical gladiator. You have to be the fighter, be the main one going above and beyond everything,” Wiley Wilson, El Camino Social Justice Center student services specialist said, reflecting on the traditional image of a warrior.

“But, I’m like – no,” Wilson said. “I like to think of warriors differently, qualities of a student having drive. What do I want to do? How do I want to move forward in my life? How can we move together as a collective? How do we make our warrior ideals and goals a reality?”

Wilson admires the warrior aesthetic of Charles Hampton Houston who spent decades challenging the tenets of the 1896 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Plessy v. Ferguson that established the doctrine of “separate but equal.” Houston’s work contributed to the eventual Supreme Court 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka that struck down Plessy and forced the integration of public schools and other public services.

“He [Houston] spent his entire life working hard to show that Black and Brown folks are able to far surpass expectations,” Wilson says.

“We should listen to Native American students on campus and look to them for guidance,” Molina Berrios said. “It’s the students who matter the most.”

But, El Camino no longer has a Native American club or an annual pow wow. Courses in Indigenous studies, culture and language don’t exist.

Molina Berrios is hopeful that will change.

“There are folks [at El Camino] working to make sure that Native Americans and Indigenous people are represented on our campus. That kind of representation will matter a lot to students,” he said.

Walking through the ECC archives she has organized over the past two years, Cain reflected on the college’s identity as warriors.

“Being a fan of El Camino students because they’re so great,” Cain said. “I would say they’re warriors against backwardness, prejudice and discrimination, things that hold them back from being successful.”

Cain looked up at the boxes that filled the archive shelves preserving student publications, minutes from campus meetings and outside media coverage on El Camino.

“The college has gone through a lot of changes,” she said. “But I think we’re getting there where it’s good for all. Everything is starting to fall into place.”

“Choosing a mascot is difficult, because historically with warriors… there’s not one universal side.”

“In my culture, warriors are resilient, and can get through hardships,” Molina Berrios said. “My community is full of warriors who have sustained our culture, who have created spaces for ourselves in ceremony, who have protected and passed down traditions and practices. A real warrior isn’t just someone going to war. It’s someone doing great work for our community.”

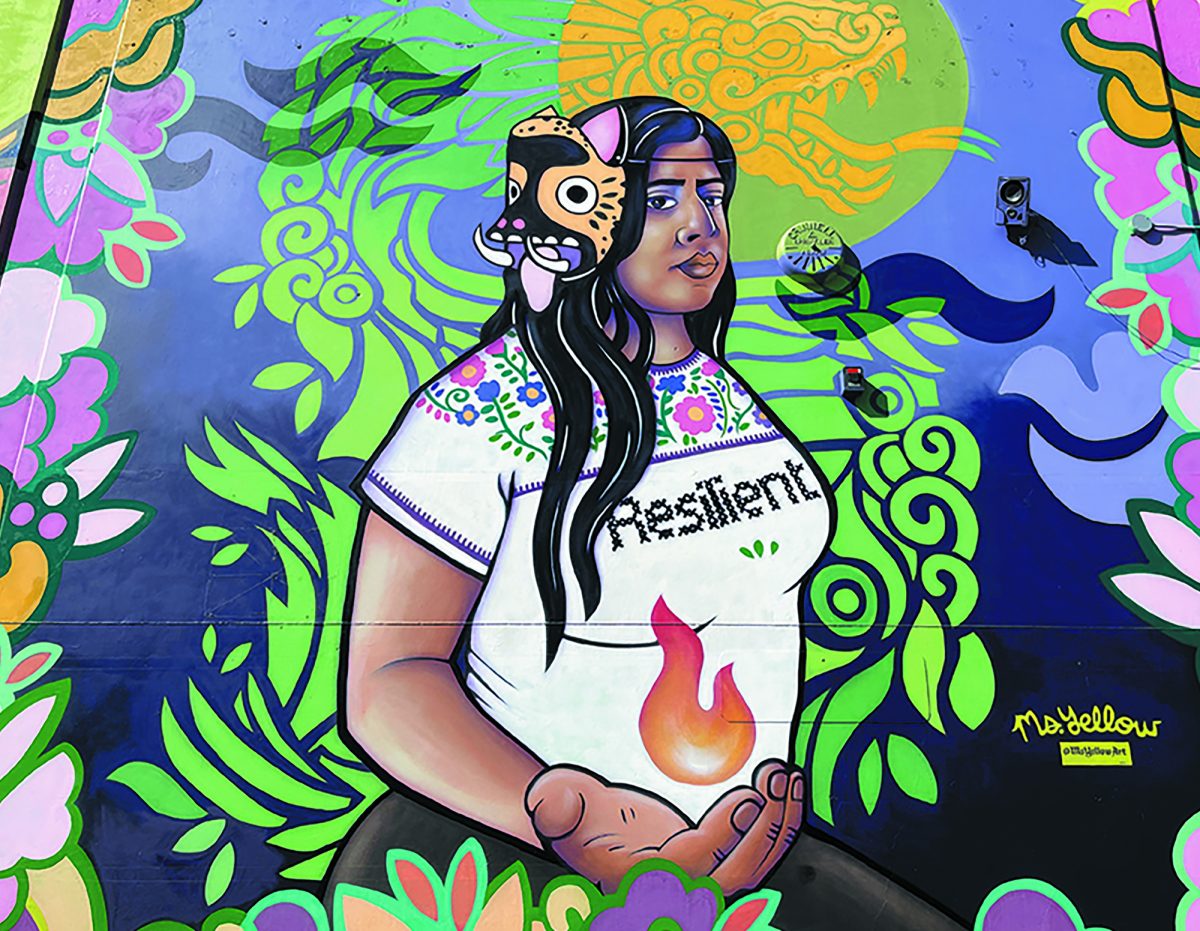

Last year, El Camino established the Black Student Success Center (BSSC) to support students who were traditionally excluded or mistreated by institutions of higher education. The walls of the BSCC also include several warrior images and quotes that promote the uplifting rather than conquering of communities.

Serving Black students on campus in her role as a student worker at the BSSC, Mason said a warrior is “resilient, someone who always triumphs, someone who continues to progress despite any adversities or challenges that they may face.”

Mason argued that El Camino needs a mascot that everyone can claim, “someone or something that represents all of us regardless of ethnicity, race or creed, something that we all share in common.”

Nursing student Amatullah Mateen said the Black Panther Party and people involved with the Civil Rights Movements were warriors and “champions” of their community.

Warriors are “protectors of their people who act with integrity,” Mateen said.

But, she added, choosing a mascot is “difficult to navigate because historically with warriors – people involved with conflict or struggle – there’s not one universal side. On the one hand, you often get into caricatures and problematic depictions of warriors. Then, on the other side, you also have to think about what they were fighting for. Not everyone will agree on a just cause.”

“There’s no use keeping a logo and name that reminds us Californians of a terrible part in American history.”

In an effort to reflect on El Camino’s warrior past and chart a possible future, several engagement strategies were implemented as a part of this investigation.

Warrior Life, The Union and ECC’s Social Justice Center hosted a campus-wide discussion on Nov. 28, 2023 attended by more than 50 people in person and several more online.

A survey was also distributed to the college community that was completed by 139 people.

To get an accurate representation of everyone on campus, and to protect against bias, the survey link was emailed to all students, staff, faculty administrators and college trustees, as well as shared on two separate days with people in public areas on campus.

The comments below credit the contributor when they included their name on the survey.

In response to a survey question asking if ECC should change its name and logo, 37 (27%) felt that neither the college name or bell logo should be changed.

One full-time professor urged no change to the college name and bell logo, writing, “No. END WOKENESS AND CANCEL CULTURE!!!”

Thirty-three people (24%) felt both the college name and bell logo should be changed.

“Now that I’ve been informed of the unfortunate history behind El Camino’s name and logo, I believe it’s only reasonable we’d change,” wrote student Deja Andrewin in her survey. “There’s no use keeping a logo and name that reminds us Californians of a terrible part in American history and an action that’s still felt in Indigenous and Latino communities today.”

Full-time faculty Azul Rodriguez suggested that the name be South Bay Community College with a pelican as the logo and mascot.

Twenty-seven people (19%) responded that the college should keep its name but change the logo.

Behavioral and Social Sciences Dean Christina Gold wrote, “I don’t think it is feasible or a good idea to change the college name, but we could emphasize the term road, pathway and try to pull away from connections to the mission system. Absolutely, ditch the bell. A road or a path leading to a star may symbolize El Camino as a pathway to success for students.”

Thirteen people (9%) were unsure about changing the college name or logo, or had no opinion. Twelve (9%) commented but were unclear on whether to change one or both the name or bell logo. One said more discussion was needed, and two left the question blank.

“The squirrels on campus are…pretty loving of people, but they will attack you if you try them. A squirrel would be an amazing mascot.”

In an open-ended question, people were asked to suggest mascots for ECC.

“Change the logo to the Chevy El Camino (1970 model, blue color),” suggested student Maple Groves.

Other ideas included a 1970 Chevrolet El Camino, Xena the Warrior Princess and various animals including an elephant, eagle or roadrunner.

One student advocated that the college be symbolized by a tree or a shell. “Both are symbols of shelter and belonging,” she wrote.

Two people suggested Marvel Comics’ X-Men.

Several people felt El Camino should abandon any link to warrior symbols or mascots because of the promotion of violence or armed conflict.

Gold wrote, “I’d like to get rid of “Warrior” because it is historically connected to racist depictions in our college history. I’d like us to move on to something less violent and aggressive.”

“Wait, the bell is the logo?” asked student Jeremy Ruiz. “Maybe change the logo to something more eye-popping. Anything that is not a warrior/gladiator theme.”

The most popular idea with eight responses was a squirrel.

Part-time professor Annette Owens wrote, “A warrior squirrel. It’s funny and it’s classically Elco. Who run the world? Squirrels,” ending her comment with a nod to “Bey,” [Beyonce] for the lyrical inspiration.

Owens also sent Warrior Life a squirrel logo she created in Adobe Illustrator.

Wiley Wilson, El Camino Social Justice Center student services specialist, said he has always thought about having a squirrel as El Camino’s mascot.

“We have so many dang squirrels around campus. If UC Santa Cruz can have a slug and there’s literally a school that has a beer keg – I don’t know how or why – then we can have the squirrels.”

Wilson shifted his stance, tilted his head and laughed.

“The squirrels on campus are extremely confident,” Wilson added. “They are pretty loving of people, but they will attack you if you try them. A squirrel would be an amazing mascot to have.”

There is historic precedent for a heroic squirrel serving as the El Camino mascot.

On Nov. 21, 1997, a campus squirrel was electrocuted when he ventured too close to an electric generator on Manhattan Beach Boulevard. The electricity on campus went out, and the squirrel earned a nickname – Volt – and widespread admiration.

Women’s basketball coach Kristy Lowesner called for the creation of a “National Squirrel Day” every November.

“Electrocuted furry friend needs day of thanks,” ran on the Dec. 4, 1997 editorial page of The Union. “Students were overjoyed,” the editorial said.

According to The Union, everyone who had tests that day or assignments due had no worries. “Volt had saved the day with his untimely death.”

The values and symbols that define El Camino – whether heroic animals or humans – might eventually represent all the communities that make up the college and the land on which it stands.

And that just might be a squirrel.

______________________________________________________________

Historical timeline on El Camino’s name, logo and mascot:

To connect to Indigenous leaders and organizations in Los Angeles County:

Los Angeles City/County Native American Indian Commission / https://lanaic.lacounty.gov / (213) 738-3241 / contact@lanaic.lacounty.gov

To learn more about the movements to eliminate images of Indigenous people and culture from education and sports:

National Museum of the American Indian Webinar: Changing the Narrative About Native Americans

American Indian College Fund’s statement: Rename mascots to end harmful stereotypes

National Public Radio’s story on New York’s banning of Native American mascots