A subtle cool breeze and the rustling of squirrels within a shaded bush. Santa Monica College continues through the afternoon with an unperturbed atmosphere.

The normal bustle of faculty and students found during the week is seldom seen on Friday.

In the distance within the Corsair Pavillion Gym, the screeching of shoes and excited shouts echo from beyond its white walls. Inside, people stand shoulder to shoulder cheering and jeering as a basketball bounces off the rim into the hands of the offense.

The ball passes to and from until it settles. The offense backpedals toward the hoop. As a player goes up for a shot, a defender raises hands to block.

The ball is passed, while a teammate waits on the corner. With a flick and a fall, the ball swishes into the net. Christopher Hurd, a man stout in stature dressed in a black t-shirt and gray Jordan sweatpants runs from one side of the gym to the other, pointing to the team that made the shot.

The team shouts the current score, 3-1. With an Expo marker in hand, he runs back to the other side of the gym.

His hirsute, unshorn countenance grinned a leaden sneer.

He scribbles the score on a whiteboard, then races back into the fray to capture the next game score across the gym. Away from this event, he works a day job.

Hurd is a counselor at El Camino College.

The 42-year-old Los Angeles resident dedicates his time to the cultivation of student success through one-on-one counseling, as well as the development of programs on ECC’s campus.

He wishes to develop and lead the next generation of counselors on El Camino’s campus.

“My not-so-secret goal is to hopefully transform the counseling space, as well as the classroom space, to increase exponentially the men of color that you see in those spaces,” Hurd said. “If I were to retire from the counseling department and see half the counselors in the room men of color, I’d be a happy person.”

Hurd’s mission is not without achievement – Armanti Weeks, a Success Coach at Pasadena City College, credits Hurd for not only his current career path but the new direction his life is taking.

“When I was about to apply to a program, I thought about how he helped me in my transition,” Weeks said.

Having been on the verge of moving to Boston, Hurd’s passion and authenticity are what Weeks attributes to his staying in California and his desire to become a counselor at the community college level.

“I thought about how he was for me. I want to take into account — I want to be like that.”

Another one of Hurd’s more recent successes was helping bring the Men of Color Action Network, or MOCAN, to El Camino, which is a program that provides men of color a space on campuses to feel heard and supported.

Academically, the student equity and achievement office created a service called myPath, which allows students to link courses together, alerting instructors to the demographic of their classes, which allows them to go out of their way and seek culturally relevant literature.

Hurd has his hands in many of many initiatives, not limited to MOCAN and the Student Equity and Achievement office, but the Black Student Success Center as well as serving within the Black Student Union as an advisor.

Through these programs and being a counselor, Hurd aims to further develop people of color within MOCAN. One of the organization’s goals is to develop fellowship between its members through various events and activities.

In addition, MOCAN provides various avenues of support, some of them being scholarship opportunities, career development workshops, one-on-one counseling and community events.

“We decided ourselves to not wait for someone to – make a change but we wanted to be the change we wanted to see,” Hurd said.

Hurd’s duties within MOCAN do not fall squarely with just meeting with students, but instead, facilitate and cultivate an environment where they can thrive as a community as well as academically.

Similarly, Hurd was a student, like the ones he guides and assists.

In 2002, Hurd was a student at Santa Monica College. Unsure of his career path, he was conflicted between becoming a longshoreman or a detective. He continued his studies, excelling with a high GPA.

Cassandra Patillo, Hurd’s direct counselor, suggested that his high grades could lead him to transfer to UCLA. With the support and guidance of the Black Collegians Program and its direct counseling efforts, he was accepted into UCLA, graduating with a bachelor’s in sociology and a master’s in counseling.

After graduating in 2007, it was Hurd’s goal to enter the community college space to be a counselor. However, due to the recession, there were few opportunities available for him to go through.

Instead, Hurd became a college counselor at charter high schools. Hurd presses the importance of those experiences for him.

“Charter schools, they work you tirelessly. But when you are passionate about the work, when you are passionate about serving the community, serving you students…its a great opportunity for you to really explore both elements of your creativity (and) both elements of your passion.” Hurd said.

Hurd’s own passion and drive to serve his community started young within his family.

His mother grew up in Birmingham, Alabama in the late 1960s during the bombings of black churches and black community centers. The intimate knowledge of the struggles that the black community had to strive for gave him an elevated level of appreciation for the rights we have today.

“The rights that we appreciate now as people of color were not given to us, but were fought and were bled for us to have,” Hurd said.

It is through this understanding that him to have the strong drive and motivation to work intimately with students of color and within these programs.

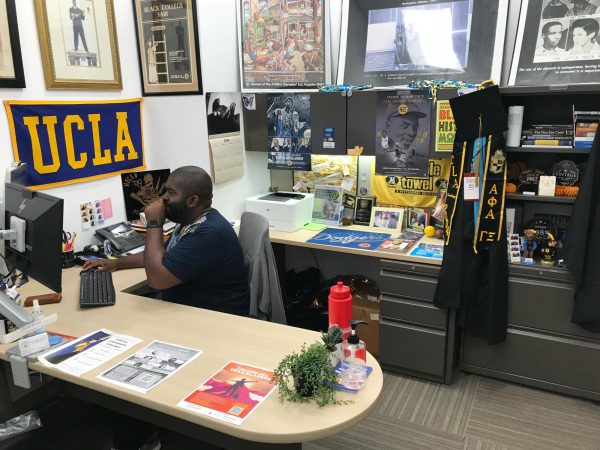

His office, located inside the Student Equity and Achievement Center within the student services building, is where the majority of counseling takes place.

A large blue and yellow UCLA banner hangs on the wall next to his desktop computer. Next to it is a black and gold plaque that has bold serif lettering that reads “MOCAN.”

“Those who look at the data, know that disproportionately men of color—make up a number… make up some of the lowest–achiev- ing groups [when] we look at equity gaps. We have some of the largest equity gaps compared to our white counterparts” Hurd said.

DiAngelo Ziy, Student representative and Head student worker for the Men of Color Action Network at El Camino College, attributes Hurd as the main reason why he went back to school.

“I lost faith in the college system after having a negative experience at a major university… and he broke down how really simple it could be if you go to the community college space that it is not as rigorous as you might think, it’s way more affordable and you’ll get out quicker than you think,” Ziy said.

As a student, Ziy attributes Hurd’s counseling methods as the foundation in allowing him to build his faith in the college space.

He continues to study business administration at El Camino and plans on transferring to California State University Dominguez Hills to study finance and psychology.

Hurd’s enigmatic personality and boisterous persona allow him ample room not for just a serious tone but to be playful and have fun with students. Just as he sits on an off-white plastic folding chair with a microphone in hand and a sly grin across his furred face, Hurd cracks wise jokes to the other teams across the gymnasium.

“C’mon you bums you can play better than that!” he said into the mic.

“Bums,” a phrase that he particularly enjoyed, as he repeated throughout the matches. Pumping his fist, he hurriedly stands up. Jostling the chair from its position to cheer on the students participating in the championship round, Pasadena versus Santa Monica.

The space that MOCAN provides allows the men the ability to express themselves in a safe yet competitive manner. These philosophies of which Hurd embodies are delivered into his counseling practices at El Camino College.

Hurd doesn’t just approach counseling from a traditional standpoint but rather, he is willing to go out and involve himself in the lives of the men and women he helps. He’s willing to put his best foot forward when he notices students are slipping through the cracks.

”Students can often be left behind and slip through the cracks,” Hurd said. “Some jump through them. As long as you are not running and jumping through the cracks. I can offer my support and help.”

Hurd often takes an active approach to his counseling, meeting students where they are. During slower days, Hurd likes to take a walk around the El Camino campus and speak to students in areas where they may convene such as in front of Cafe Camino.

Students often rush to him, asking questions that plague them.

“We’ll go to where students are to seek them out, to make sure they are getting information,” Hurd said. “Because sometimes, though, the school does a great job sending information via email and text. Students don’t always read those. So obviously, face-to-face contact is the best way of communicating with students.”

Hurd is not alone in his efforts to provide a more equitable El Camino, as he attributes his numerous successes in the programs offered by El Camino to his colleagues Robert Williams, Keiana Daniels, and Nayeli Oliva.

These are just a few names that Hurd mentions as anchors of progress to what he continuously strives towards.

It is through the efforts of an active, willing, and strong faculty, such as his counseling colleagues, that he accredits their ability to impact more students’ lives in a meaningful capacity.

With a focus on bridging the gap between academic and athletic events, such as the basketball game at Santa Monica College, it presents a familiar environment to engage with students.

Within the years of counseling hundreds of El Camino students since 2016, Hurd said it’s important to embrace the struggle as one of the key takeaways of being a student.

He affirms that it’s ok to go through difficult times and what is most important is to stay passionate and to stay motivated on desired goals because once those goals are reached there will always be more work to be done, so enjoy the journey.

“Failure is a life lesson, not a life sentence. Unless you stop trying,” Hurd said.