Some of the most vivid memories I have of growing up are of my family eating dinner with a Univision 34 telenovela.

Unfortunately, that’s pretty much the extent of my “Mexicaness.”

While both sides of my family hail from Mexico, I was first-generation on my dad’s side and second-generation on my mom’s.

My mom was born and raised in California and is more familiar with Westernized culture. This created an interesting crossover in how I was raised—Westernized with Mexican values.

I resemble what many would consider to be Mexican traits—brown skin, brown eyes, dark hair, and a wide nose. I am also fluent in Spanish.

However, my physical traits are overshadowed by my personality and lifestyle, which make me feel like an imposter in my culture.

In 2017, the Pew Research Center reported that 5 million Mexican Americans feel a separation from their culture.

It’s a little hard to feel Mexican when your dad gives you one of the most American names possible – Emily.

He was trying to be more “American.”

Emily sounded unnatural to Spanish speakers, so my family opted to call me by my middle name, Alina.

Hearing my sister and cousins go by their first names always triggered some jealousy because their names were pronounceable enough, unlike mine, which had to go by a different name to fit into my family’s native language.

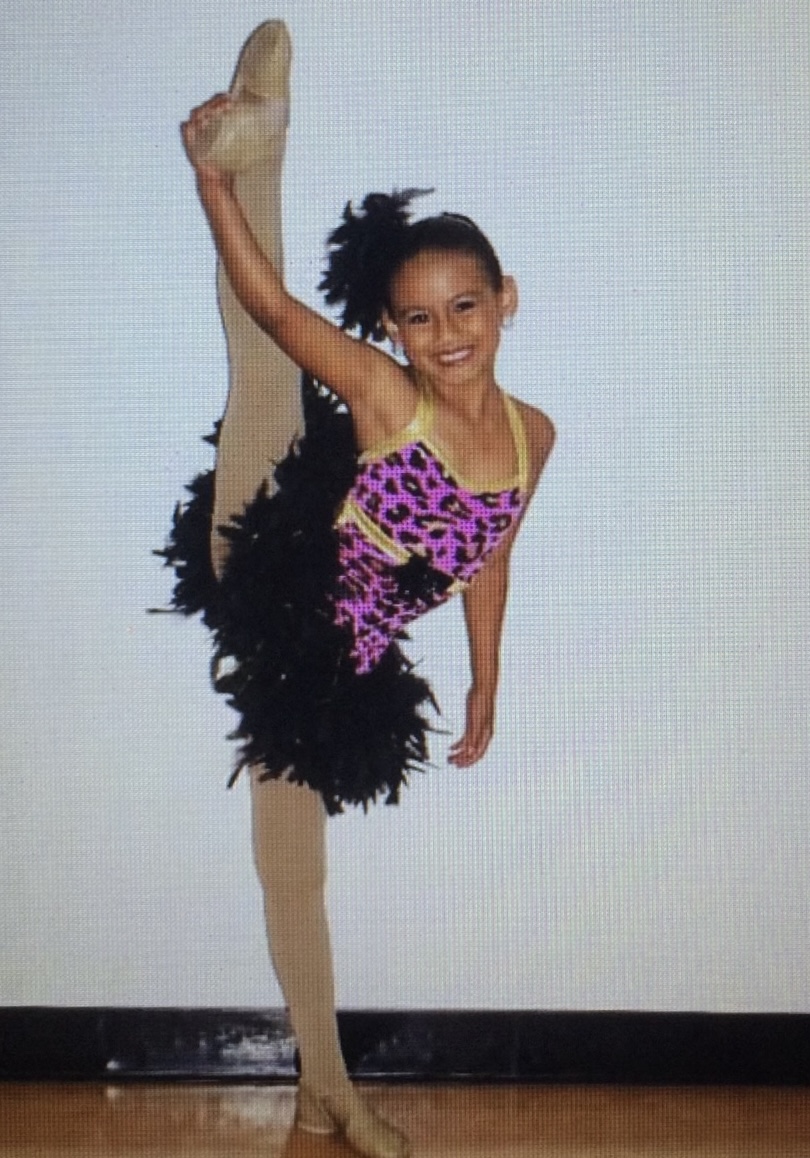

As a child, I was introduced to an Americanized form of dance: commercial dance. This included jazz, tap, lyrical, ballet, hip-hop, and other styles.

I became a competitive dancer, something no one in my family had ever done.

Though I loved it, my paternal side of the family never fully understood my dance style. My grandma often verbalized how uncomfortable she was watching me raise my legs and parade around onstage in two-piece costumes.

My cousin was also a dancer, but she trained in folklorico. Since this style originates from Mexico, my family connected with it, and my aunts grew up performing folklorico.

Seeing their genuine reactions to her routines and traditional outfits and hearing the constant adoration for representing Mexican culture made me feel disconnected and as if I was not representing my family the way I should.

To try to feel “more Mexican” and to find common ground with my aunts and grandma, I asked my aunt to sew me a folklorico skirt.

With joy on her face, she made me a big, bright red and green skirt. My cousin began teaching me basic steps so I could better understand why my family loved it so much.

Even with this effort, the life I was and continue to live is a different world from what my aunts, uncles, and even my dad lived.

I cannot relate to living life on a ranch, having knowledge of Mexican politics and pop culture, or experiencing the Mexican education system – making it difficult to join in on familial conversations and feel connected to my culture.

Even my food preferences separate me from my family and culture.

Trying new foods has never been my strong suit and Mexican food is no exception.

When I was younger, I often refused to eat traditional Mexican meals such as Chile relleno, mole, menudo and others because they “smelled weird” or “looked funny.”

Rather than being force-fed the meal, my sweet maternal grandma, who loved to spoil me, would make me a separate meal. So, while everyone was eating chile relleno, Miss America ate steak with rice and salad.

My preference for American food over Mexican often results in disappointed or disapproving looks from my family members, along with comments like “Aren’t you Mexican?”

To my sister, it seems that I’m not, as she loves to remind me that I’m not “Mexican enough.”

She teases me about my California vocal fry, calls me “basic” for listening to Beyoncé and Ariana Grande rather than Mexican artists like Los Tucanes de Tijuana, and nags about my fashion taste.

“You’re such a white girl,” she says when I come out of my room wearing jeans and a crop top, a pretty typical 20-year-old American girl outfit.

While I’m used to it, it only fuels that disconnection I feel with my Mexican heritage.

As I struggle with feelings of disconnect, I must remember that my family immigrated to the United States for one purpose—to give me a better chance at life.

And that, they have.

Slowly, but surely I am understanding that my American life will not fully coincide with my family’s struggles, experiences, and preferences, and that is OK.

I need to be proud of my American life and try to learn more about my Mexican heritage. Whether I ask family members for stories or do my research, it is important to act now while I still can.

I may have American customs, but it does not discredit my Mexican heritage.

Now turn on some Beyoncé and take me straight to In-N-Out.