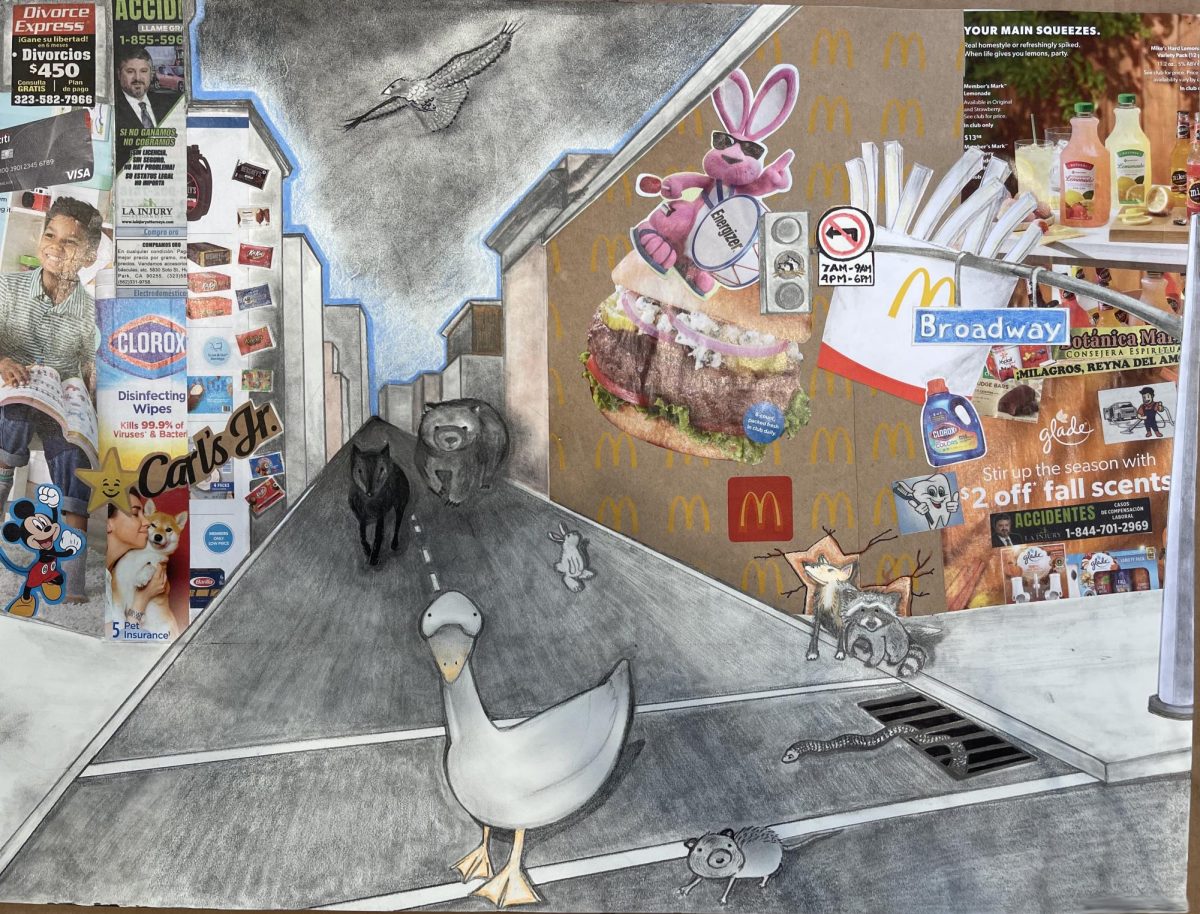

Four days before Americans elected Barack Obama president in 2008, I was sitting on the hard plastic back seat of an LAPD squad car parked on the corner of Manchester and Figueroa in South Central Los Angeles.

It was a seat designed to survive the blast from a strong water hose to wash down blood, urine and vomit. The seat looked like it hadn’t been cleaned in forever.

I shifted to ease the growing pain in my shoulders caused by the hand-cuffing of my wrists behind my back. A giant, muddy orange moon sat on the horizon, casting shadows across the asphalt. A man asking for money in the Popeyes Chicken drive-through line gave me a sympathetic nod.

Staring out the window, my head was drowning in questions. Would my car be impounded? What would happen to my backpack, wallet, computer and phone? How would I contact my job to say I wouldn’t be there for days? Who would get food and water for my dogs?

I was one of more than 17,000 people detained in Los Angeles County that night, 72% pre-trial, most for non-serious, non-violent charges, who were locked up only because they were too broke to pay bail. Their “crimes” were connected to living on the street, driving without a license, public intoxication, experiencing a mental health crisis, selling sex or possessing small amounts of drugs.

That night, the jails across the nation were filled with people who deserved better.

They still are.

After hours in a holding cell in the basement of the LAPD’s 77th Division, I was booked on a warrant and also on driving with an expired registration, fingerprinted and photographed. An officer in plastic gloves used a long Q-tip to swab the inside of my mouth for DNA, and I was transferred into a cell.

I have been locked up before and since, in addition to the LAPD’s 77th Street Division, in the LAX Airport and Van Nuys jails; Century Regional Detention (CRDF) – the main L.A. County women’s jail in Lynwood; The Tombs in New York City; and shorter detentions in various police stations and courts.

But that week in 2008 was different.

Everyone in the nation seemed to be talking about the possibility that the U.S. would elect its first Black president, including the people I was locked up with in L.A. County.

For hours overnight after being booked, and for another hour at the midway bus transfer holding area outside Men’s Central Jail on the way to court on Monday morning, and then for eight hours again in the holding cells beneath the court — the conversation was legitimately hopeful.

People talked about the historic possibilities of that year’s election. We talked with once-in-a-lifetime whispers that maybe, this time, things really would change. The wars on the poor, the wars on “gangs,” and the wars on drugs, would crumble. People would get some financial help and jobs that pay enough to live on. Mothers would be reunited with their children. Banks would be punished for their sins, and people would be able to keep their homes.

White, Brown, and Black women all raised hopes that they would be out in time to go to the polls. Many said they had registered for the first time. Two Black women cried because they knew they wouldn’t be released in time to vote.

Because of the importance of that moment for all of us, I have etched these women, their stories and everything that happened that weekend into my memory.

One woman booked on a DUI spoke about what she would have to do to survive once she was fired from her job because she couldn’t have contact with the system.

Another woman cried when she expressed her fears that her ex-husband would use her arrest as leverage to take her children from her.

A woman who already had two prior DUIs was devastated that she could go to prison. She sobbed that she didn’t know where her child was because she couldn’t reach her mother to advocate for the baby’s release from child welfare (DCFS—Division of Children and Family Services) custody. Nearly every woman who left custody from that cell—leaping up as their name was called — turned to her and promised they would try and reach her family.

Before dawn on Monday morning, shackled at our ankles, wrists and waists – and also chained to the person next to us – we waited in line to board the giant black and white L.A. County Sheriff’s bus to court.

The bus had already made stops to pick people up. As we climbed onto the bus, we filled a few rows of battered seats in the front that were reserved for people labeled as female. Two men sat in floor-to-ceiling cages — deemed by the system as requiring physical separation from other people — with openings so tiny that fingers couldn’t fit through the metal grates. The majority of rows in the back were filled with men similarly shackled as we were.

Usually, Sheriff’s deputies and the driver are on the bus. But on this day, for a reason never shared with us, they left us alone on that bus for what seemed like at least an hour. I have never experienced the bombardment of sexually explicit language hurled at people as I heard coming from the back of the bus on that day.

A few men began to speak in a low tone, seductively and honey-tongued, casting their comments out toward a specific target, describing her, pleading with her, detailing what they’d like to do to her.

Some women failed to respond. Others shouted for the men to stop or insulted their looks or chances.

Then, the comments from the back escalated dramatically to furious curses and violent threats. Some women tried to fight back verbally. But we were small in number and the noise pollution overpowered us until the deputies boarded the bus.

I admired and loved the women for their courage.

In the holding tank at court, a young woman from Mexico cried for hours. She and her husband were pulled over in their car a few months earlier and arrested for not having documents. Her baby was taken into DCFS custody. The parents were later deported – signing away their rights to an immigration hearing because they feared being detained for months without their child.

Back in Mexico, she desperately contacted DCFS over and over to get a court date to regain custody of her baby. She entered the U.S. for that family court date, was stopped and arrested in L.A. for driving without documentation, and was now frantic that she would miss court and lose her child forever if she wasn’t released in time. Without pen or paper, I repeated with her over and over the names of immigrant rights organizations she could call for help.

Among the women, there was occasionally a harsh word, but there were many more unbelievable acts of kindness: patience offered to someone who was muttering to herself, hallucinating, and occasionally screaming out obscenities; care and comfort and embraces given to the desperate mothers; the sharing of food and blankets; and the women who cleaned the filthy cells, picking up discarded food containers and tissue so that all of us might be more comfortable.

A lot of details about that weekend also reflected the realities of jails and prisons.

Jails, prisons, juvenile halls and ICE detention centers extract thousands of dollars from families who are struggling financially, punish broken people, torture abused people, make addictions and afflictions more severe, deny sick people quality medical care, grow violence, depression and hate, and dump people back onto the street much worse – financially and emotionally – than before we were arrested.

There’s a distinctly sweet and rancid smell to nearly all the lock-ups I’ve been in that’s embedded in my memory – a combination of tasteless, carbohydrate-saturated food and the use of damp towels that turn sour with too many uses without washing.

Sometimes, the smell is much worse. Once at the Van Nuys Jail, I was locked into a group cell where several bunk beds were maneuvered like Tetris to fill the space. The stench was overpowering — menstrual blood, urine, perspiration and clothing that had been on one person so many weeks without washing that it was impossible to tell its original color or shape.

An elderly woman apologized to all of us. She spoke with humility and dignity. “We have been in here for days with no access to a sink,” she said. “Some of us came in off the streets already stinking. We are really sorry.”

Each strip search is dehumanizing, removing clothing in front of strangers and having to bend over and spread your butt cheeks. I was part of a class action lawsuit involving 93,000 women incarcerated between March 2008 and January 2015 that exposed details of this horrific practice at CRDF, resulting in a $53 million settlement. Similar practices still take place across California and the nation, except where facilities invest in body scanners.

Guards find the most intimate ways to belittle and disrespect you and everyone around you. They ignore pleas for essential supplies like toilet paper or menstrual pads, fail to respond when people beg them to open a cell to pee, or urge them to call medical staff for someone who is sick.

The blasting of air conditioning ensures frigid, sleepless, torturous nights. The lack of air conditioning on hot days can cause heat stroke and occasional fatalities.

Health care is inadequate and substandard. During the COVID pandemic, American jails and prisons were second only to nursing homes in having the highest number of deaths. During wildfires, juvenile halls, jails and prisons have put numerous lives at risk by failing to evacuate quickly and efficiently.

Even most of the staff have no faith in the system’s claims that jails and prisons help people. There’s a cold-hearted line that guards often repeat when people are released — “We’ll see you back soon.”

I was released late at night on November 3, 2008, in time to vote on Tuesday.

As the election results came in, a wave of hope washed over my community.

But over the next two years, it quickly evaporated.

It took until 2015 for Obama to comment on mass incarceration — seven years into his eight years as president. He didn’t appoint anyone as head of the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention until year five.

He deported more people than any other president in U.S. history — the greatest number from L.A. — and left Guantanamo open in spite of his campaign promises.

Obama spoke of the struggles of young men of color and then claimed the issue was mentorship, getting them to “pull up their pants” and prepare for a job market that still had nothing to offer.

His administration visited Ferguson and, Baltimore and Cleveland acknowledged that police policies were killing Black and Brown people, but then defied community calls for civilian oversight, independent investigations, and alternatives to police in schools and communities. But, the administration pushed body cameras and police training.

Instead of funding our dreams, the administration spent billions of dollars each week on troops and drones in Afghanistan and Iraq.

This is not to say that I don’t miss the dignified, intelligent leadership of the Obama administration, especially compared to the four years that followed his terms.

But, the significant changes that have been won — to reduce jail and prison populations, to decriminalize drugs, to challenge the death penalty and extreme life sentences, to eliminate court and probation fees and fines, to increase police accountability and oversight — these changes have been made by the mass movement led by formerly incarcerated people, people still inside and their families.

Still, despite this historic progress, things for women have gotten worse. Decarceration efforts are leaving most women behind.

According to the Vera Institute of Justice, “the number of women incarcerated in the United States has skyrocketed in the last four decades, increasing 475 percent in 40 years.”

Women have become the fastest-growing population in jails and prisons. While men’s jail populations fell 9% from 2008 to 2018, women’s jail populations grew 15 percent. In state prisons across the U.S., women’s incarceration rates are also climbing at double the rate of men’s.

In some ways, we should go back to the future. Fifty years ago, nearly 75 percent of counties held not a single woman in jail.

Almost all the women I was locked up with in 2008 were there because they couldn’t afford bail. They could have been given a desk appearance ticket to show up at court, which also would have saved L.A. County millions of dollars a year in policing, court and jail costs. In 2023, L.A. County is taking steps to reduce cash bail, a small but increasing trend among U.S. counties.

There’s a growing movement in the U.S. and internationally calling for the abolition of cages.

Across the world, countries are rejecting the policies, policing and punishment systems that the U.S. has been exporting for decades.

We can break from America’s addiction to incarceration and build a world without prisons.

It will save billions of dollars that can be invested in employment, education, harm reduction, mental health care and housing – the essential services needed to reduce crime and increase safety.

Most importantly, it will also save lives lost to the epidemics of suicide, violence and disease that decimate detained and incarcerated people and even the jailers. Law enforcement and prison guards have the highest suicide, substance abuse, domestic violence and child abuse rates of any profession.

Because, no one can get well in a cell.