Everyone thought Luke* was the perfect boyfriend for me. He was Asian-American from a biracial home studying computer science at UC Santa Cruz. We bonded during freshman year over a love of video games, zombie movies and “Doctor Who.”

We were dating by our sophomore year.

On the surface, everything looked perfect. We were two nerdy teens who found each other on a summer night at a bus stop across the street from the Santa Cruz Beach Boardwalk. Luke was singing “Still Alive” from “Portal,” and I joined in. Some would say the rest was history.

But after eight months of dating, I ended the relationship.

If anyone asked, I said we weren’t compatible. In reality, things were more complicated.

The truth is this; I’m part of a rare group. This is a group that totals 1% of the population.

I am asexual.

Asexuality is a lack of sexual attraction or a lack of interest in sexual activity with others. It is often described as existing on a spectrum. Those who identify as “ace” can still have sex or be repulsed by it. We can crave romance or forgo it all together. Some may choose to marry and have children and others don’t.

Asexuality is an orientation, just like heterosexuality, homosexuality, and bisexuality.

So why did I date a man who I wasn’t really into?

We got together because everyone we knew was starting to pair up. After a year, it felt like the next step in our relationship. Neither of us had dated before, and outside pressure pushed us together. I liked Luke, but I didn’t share the attraction for him that he felt for me.

My friends told me to give him a chance anyway.

“You’ll like him the more you get to know him better,” they said, insisted even.

Worst. Advice. Ever.

Our last date didn’t end well. We went to the movies on a Friday in downtown Santa Cruz. Without warning, he leaned in for a kiss. It would have been our first.

That is, if I hadn’t swerved out of the way.

Later, when asked how my first kiss went, I said that I didn’t have one.

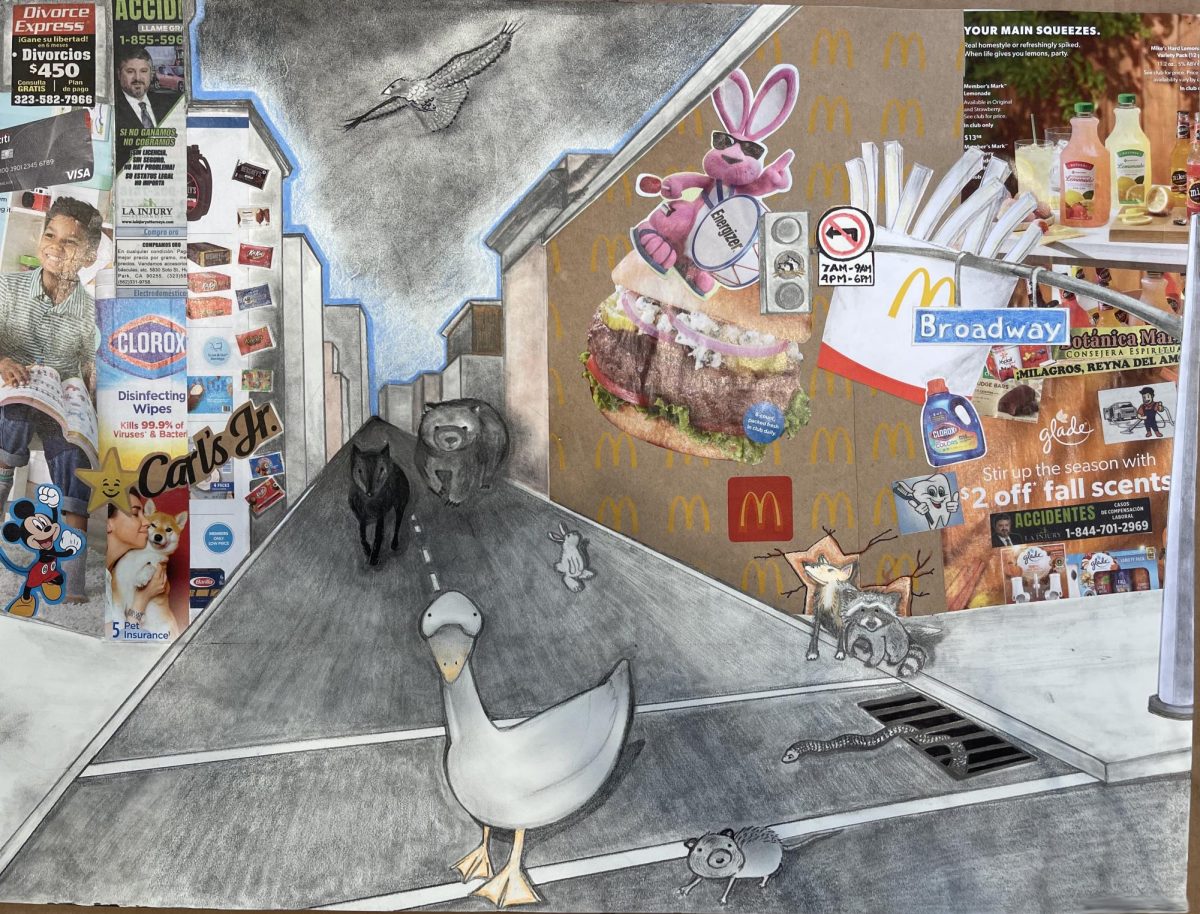

“Why not?” My friend Kim sat across from me, staring with narrow eyes, her arms folded over her chest. Behind her was the “Stud Wall,” a collage of shirtless male models and actors she and her friends had curated for years.

I stared past Kim, glaring holes into the space behind her. “Christ,” I thought. I never liked that wall.

Sex was everywhere and I hated it.

“I don’t know,” I snapped. “I think I’m asexual!”

By the time I was 20, I knew I wasn’t straight. I couldn’t call myself gay, either. I never had crushes. While I found some celebrities attractive, I liked them more for their acting or their music. I hated “The Notebook” and couldn’t get why everyone wanted to see “Magic Mike” so badly.

In the seventh grade, I threw up after Sex Ed. I later blurted out to the nurse that I never ever wanted to have sex. Like, ever.

No wonder H.R. Geiger made his Xenomorphs look so phallic. Sex organs just looked so alien.

Kim gaped at me with wide eyes. “What? You can’t be asexual. Only sea sponges are asexual!”

According to the Human Rights Campaign’s 2021 LGBTQ Community Survey, 82% of asexual people reported that they faced mental health challenges. This comes from the stigma associated with being ace. Often, we are told our identity is a phase or that we “haven’t found the right person yet.”

Thirteen years ago, there wasn’t a dialogue about asexuality.

The first and only time I visited the UC Santa Cruz LGBT resource center ended badly. The student volunteer on duty didn’t know what asexuality was. When she asked another volunteer for help, her colleague had never heard of asexuality either. She seemed unsure if they had any material about it.

Since then, the so-called “invisible orientation” has become more visible. There is more asexual representation now than it was over a decade ago.

According to the UCLA Williams Institute, “Asexuality is an emerging identity. We expect that the prevalence and understanding of asexuality will grow as more youth reach adolescence and become familiar with the identity.”

In the meantime, I just thought there was something wrong with me. I wasn’t asexual. I just hadn’t found “The One” yet. I just had to put myself out there more.

Dating felt like a chore. It was an entry on a “To-Do” list that was put off as much as possible. Dating apps were treated like junk mail catalogs destined for the trash.

I pushed myself into dating because I thought it was something you were supposed to do in your 20s. My mom was always talking about how her friends’ children were getting married and having kids of their own. Pressure to find someone was mounting the closer I reached 30, and more of my friends started to settle down.

I never thought I’d find validation on Netflix.

In season three of “Bojack Horseman,” Todd Chavez reconnects with his ex-girlfriend Emily. Things seemed to be going well, but not quite. In the episode “That Went Well,” Emily finally asks Todd what his deal is. Does he like her or not?

“I’m not gay,” Todd says. He looks down at his ice cream sundae, absentmindedly fidgeting with the spoon. “I mean, I don’t think I am. But I don’t think I am straight, either. I don’t know what I am. I think I might be nothing.”

I choked on my beer.

That episode finally put to words what a decade of Google searches couldn’t.

In hindsight, I wish this representation existed ten years ago. Maybe it could have made navigating relationships in my 20s manageable. Maybe it would have made coming out easier if I had something to back me up. Who knows.

What I do know is this.

I am asexual, and that’s okay.

*Author’s Note: Names have been changed to maintain the confidentiality of those involved.

LGBTQIA+ resources are available to El Camino College students in campus resources and can be accessed in person through the Social Justice Center in the Communications Building, Room 204, or online at https://bit.ly/3MohcNz

For more information about asexuality, visit the Asexuality Visibility and Education Network website at https://www.asexuality.org/