Dec. 28, 2020.

I was at home watching a documentary on Netflix about Aaron Hernandez, the former NFL star turned convicted murderer when I received a life-changing phone call from an unknown number at 4:47 p.m.

After exchanging pleasantries with a social worker on the other line, the next line of dialogue sent shockwaves through my body.

“I’m sorry to have to be the one to inform you, but your father passed away,” the social worker said on the other line. “He passed away on Dec. 19.”

My dad had been gone for nine days, and I did not know. He was 59 years old.

The woman on the phone said it was due to miscommunication among staff members of the hospital.

I was LIVID.

I was processing a barrage of different emotions. And after five days of trying to locate the body, I eventually found him with the help of a funeral director.

After months of personally investigating, I learned a nurse had found him unconscious after suffering a heart attack triggered by COVID-19 in the hospital. My dad had been in the hospital for more than two weeks to receive musculoskeletal treatment, as his joints and muscles had been weakened.

Little did I know my father’s passing would lead me to letters he had written, as I was clearing out his apartment.

After reading several letters he had written over the years by hand and by computer, two, in particular, stood out.

The first letter was an impact statement, documenting the excruciating manipulation and the mental, verbal, and emotional abuse he endured from several relatives. Like my dad, I also had been a victim of the same types of abuse carried out by the same relatives.

The second letter, which had been addressed to me, encouraged me to discover happiness in life in a variety of ways. It directed me away from the trauma that haunted me for so long as a result of the manipulation and abuse from relatives.

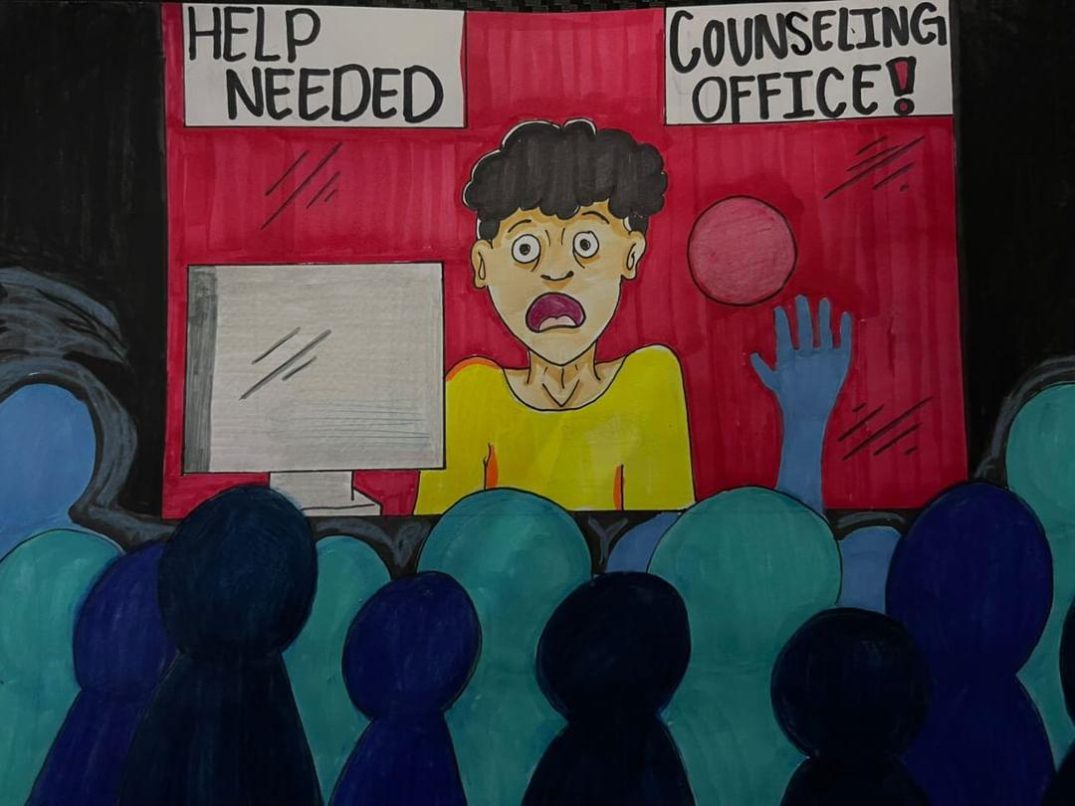

The anxiety and depression I felt were internally prominent, but my closest friends read me like a book and understood where I was coming from.

Like me, some of those friends of Filipino descent fully understand how demoralizing growing up in a culturally toxic environment can be. In fact, I hate calling it culture.

It’s not culture.

It’s a series of illogical concepts and toxic behavioral patterns passed down from generation to generation. Dad acknowledged this and knew, it had also affected some areas of my life.

But, I digress.

It’s almost like he was meant to write those letters, only for me to discover them after he passed. For months, I was deep in thought reflecting on the letters and my past, which I understood to a degree.

As I reflected back on my dad’s incredible, yet tragic life, I also acknowledged it was time for me to start making the changes he talked about.

The youngest of nine children, dad grew up poor on a farm in the Maguindanao province of the Philippines, snacking on salted rice as part of his meals. In 1978, my grandfather passed away from tuberculosis. Dad also experienced the same feelings of regret after losing his father, the same way after I lost him in 2020.

In 1981, he left the farm to pursue an education in Manila, the country’s capital, leaving his family behind. While working on his education in Manila, he worked in a hospital as a clerk.

In 1987, he obtained his degree and eventually moved to the United States by himself. He was the lone sibling to get an education and live in the U.S.

I took time to understand the reasons for the generational, toxic patterns of our familial abuse and their hidden agendas, simply because of their harbored feelings of anger against the world.

The intense, rippling effect of regret, anger, and anxiety echoed within the time I reflected on not only my dad’s life but the trauma I experienced as well.

I was not angry because he was no longer around, as death is part of life.

More so, angry at the fact that several of our ingenuine, narcissistic relatives proudly prevented dad from realizing his full potential as a human being. In addition, I was angry and disappointed in them because different fields of my life had been manipulated. I knew eventually I had to let those emotions go.

I yearned for freedom.

Despite numerous health issues and abuse that dad experienced for over 20 years, which included an already weakened immune system and a brain tumor diagnosis in March of 2000, he still managed to love and care for people the way he did.

A 59-year-old with the body of an old man did not stop him from checking in on me. He would offer to pay for my meals and take me to places such as the park to spend quality time.

When I began digging into my family tree and history on my maternal and paternal sides, my dad would tell me stories about my grandparents. Stories I have longed to hear, as he knew how passionate I was about discovering my genealogy.

According to an African proverb, “when an old man dies, a library burns to the ground.” Taking this into account, it would be up to me to save pieces of my family history.

As we grew distant over the years, dad’s persistence in wanting to be a part of my life was still there, as he was my father.

My one and only father. The never-ending toxicity within the family put a wedge between us. As a result, I lost some years of our father-son relationship.

Reflecting on my dad’s life, even in the face of emotional hardship, I realized I had to overcome life’s obstacles, the same way he did. I eventually switched careers after leaving behind a career in public service, something I loved, but did not envision staying long-term.

This career change led me to the decision to go back to school to pursue two different degrees, one of them being a graduate degree. Additionally, I left a relationship with a woman I knew was not serving me well, along with other difficult transitions.

I did it in the name of taking care of my mental health and exponentially growing as a person.

It was not an easy transition, but I was grateful to leave with lifelong lessons that I knew would serve me for the better down the road.

Thankfully, I had good people in my circle who genuinely expressed their love and support. These people included my friends and cousins who I discovered a couple of years ago.

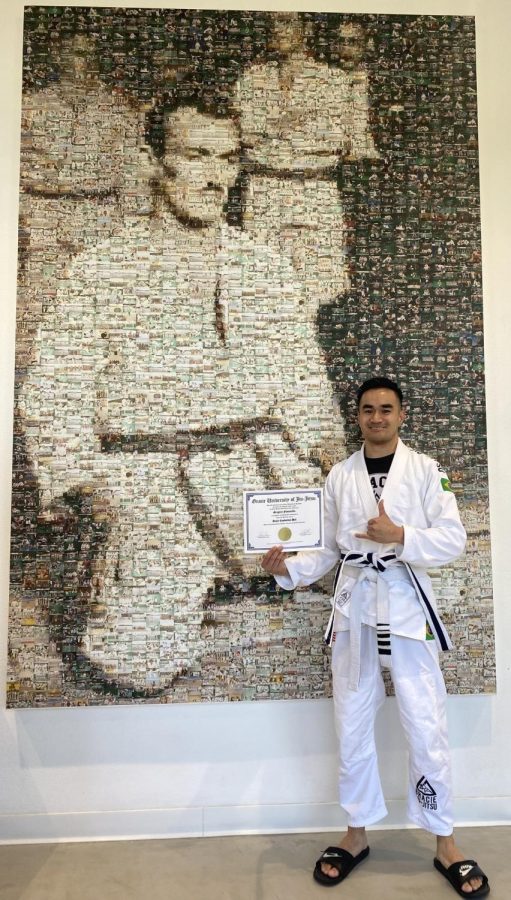

After almost a year and a half of growing pains, I rediscovered Brazilian jiu-jitsu, which I started a little over a decade ago. However, due to the turmoil among my toxic, extended relatives, along with other commitments, I had no choice but to put a halt to the sport.

In a chain-reaction fashion, 11 years later, I made the decision to get back into training jiu-jitsu. Confident and armed with life experience and wisdom, I stepped into one of the world’s top Brazilian jiu-jitsu training facilities in March of 2022.

Although I had been 11 years removed from the sport, I found myself to be “rusty.”

Talented, but rusty.

It felt like I was pushed back to square one, but reminded myself I wanted this for me, as jiu-jitsu puts you in positions where you can control, escape, or even attack an adversary without injury.

Spending almost a year relearning some of the techniques I had previously learned over a decade ago and learning new ones, I obtained my promotion belt on Jan. 17.

Reflecting on this accomplishment, I realized I found my niche.

The belt isn’t just any belt. For me, it’s a transitionary period of life; leaving behind the old, and ready to continue the growth I’ve wanted for so long.

Having been a triple-sport athlete from middle school to college, and regularly playing in recreational volleyball leagues, I have been a part of organized team sports, although track and field can be considered an individual sport.

However, I sought out a sport that emphasized control when being attacked. I found that in jiu-jitsu early on.

Jiu-jitsu isn’t just a sport. It’s a lifestyle; a way of living. Life application that you can translate to any field of your life.

For instance, a 5-foot-2,135-pound person can be pinned down in a physical match by a 6-foot-3, 250-pound individual. Intimidating as it may seem, proper leverage and technique will allow you to control such adversaries.

Just like life, the feeling of being trapped is understandably difficult and can be at times, impossible to escape. However, it is about what you do during those times, finding a way to find leverage and technique to face life’s shortcomings and overcome them.

It’s a chess match, keeping your emotions in check.

Looking back, I can only laugh. He would be so proud, as that is what he would have wanted for me.

If only dad were around to see just how independent and free I have become and grown as a person.