Losing a leader

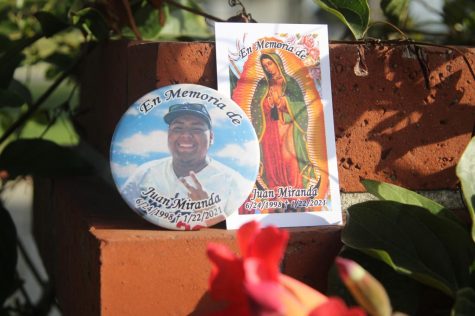

In winter the front yard plants wither and retreat into their roots. For this small house in Los Angeles the seasons bring life and death. Juan Miranda, 22, died in winter but his final work was complete by spring.

Juan remains an enigma if not at fault of his shyness, at fault of strenuous world circumstances which have plagued the lives of every person. And at the same time, Juan remained genuine. He acted for others equally whether they be family, a friend or a coworker. He made himself available for any task which needed tending, only reserving time when a Dodger’s game was on.

A journalist by nature, a baseball fan, a young college student already awarded at a state level, a relatively quiet fall compared to the avalanche of deaths COVID-19 has claimed so far.

Juan died on Jan. 22, 2021, from thrombosis yet remains a central force in the minds of those who knew and loved him. A mark unyielding and foundational. The mere mention of his name brings smiles to people’s faces. Through short laughs and shrugs, they piece him together. A hard worker, a selfless person, a funny and charismatic man.

He was the youngest of eight children. The baby of the family his brother Jose Miranda, 25, said. Being the youngest one earned him special treatment as his mom, Adela Miranda, would always let him eat whatever food he wanted while the rest had to settle for what was already prepared at dinner. But Juan was humble his brother Jose said, never liked to brag or worry his mother with complaints. Not even making big deals out of his academic achievements. Juan moved quickly from staff writer to managing editor at The Union to Warrior Life magazine editor-in-chief, a position which normally extends across two semesters but one Juan was only able to retain for one before his death.

During his first semester on staff for the student paper, The Union, Juan helped write a piece on the homeless encampments on the El Camino Colleg campus. When the story won the Best of SNO award, he told his brother about it almost in passing.

“And this is something that always [characterized] my brother, that he was so down to earth. He was like ‘oh, I got an award last night,” Jose says.

He’d found out about it while dropping off Juan for class one morning.

“It was kinda hard for my parents to see because my parents don’t understand English that well, you know, and I told him that I was proud of him that day,” Jose says.

They’d been raised in a loud and eventful immigrant home with a pug named Kobe and a little old chihuahua named Emi. Juan’s parents arrived from Guerrero, Mexico, in the late ’80s and raised a family of Dodger’s fans. Their love for the team had flourished thanks to their neighbors who befriended Juan’s family early on. Jose recalls their neighbors took both of them to their first Dodgers game as children and from then on, they were hooked.

A sporty family, Juan and Jose were in a soccer team together when Juan was in high school. In the early summer of 2013 they won a soccer final, Jose says that was one of his favorite memories with his brother.

To Diego Flores Perez, Juan’s best friend, he was like a brother. They had known each other since 2014. It was Juan who challenged him during discussions in a political science class they took together at ECC. It was Juan who taught him empathy and who, he says, is the person that made him who he is today.

But it was Diego who convinced Juan to join the student paper, and he who told Juan to keep pressing a source on his first story for an interview. Scoring interviews became easier for Juan after that.

“He’s a fast learner,” Diego says.

He recalled Juan with joy. Simultaneously struggling to find the words to describe him and then struggling to find the words to describe how he’s bad with them. He’d learned of Juan’s death when a mutual friend of theirs called him to ask if it was real. Diego, not knowing what he was talking about at first and subsequently refusing to believe him, called Juan’s phone twice. The first call went to voicemail. That worried him. It was unlike him to not pick up his phone, Diego said. On the second attempt it was Juan’s nephew who picked up his phone, that’s when Diego knew it was true.

“I think just some days it feels a lot more lonely without somebody to talk to and like, that’s when it actually gets me,” Diego says.

Their friendship was playful. Filled with jabs and teasing but unlikely at a closer glance. Diego is a devout Catholic whose favorite soccer team is Chelsea, and Juan was an agnostic whose favorite soccer was Manchester United. Juan would always meet him face-to-face Diego says, never letting their differences stain their friendship.

While self admittedly an “indoor person,” Diego was not shy when it came to partying and neither, apparently, was Juan. They had a love for going downtown together and would save up money for their occasional trips. Juan was especially fond of Little Tokyo and enjoyed eating ramen. Perez, a more frequent drinker than Juan, would also take him to bars.

On one occasion after Juan was gifted two free tickets to a USC vs. Stanford football game, they asked around for a nearby bar after the game. To their surprise the quiet drink they had imagined turned into a more eventful night. The bar was hosting a rave which ended with Juan and Diego lifting up a man they’d just met over their shoulders and nearly getting into trouble. But it was always good fun.

On a separate occasion, Juan was invited to one of his editor’s 22 birthday. Sparring the details, Rosemary Montalvo, a photographer who worked with Juan at The Union, says the party revealed a much livelier side of him.

The last time Diego and Juan saw each other was when Juan took an Uber to his house, honoring their tradition of having a drink at the end of each semester. Diego says he was concerned about Juan leaving his house during the pandemic as Juan had asthma and was more vulnerable to COVID-19 than others, but he didn’t send Juan back home when he arrived.

They shared a drink and pizza. That was the first time Perez’s father met Juan, as well as his sister-in-law. Diego recalls that as Juan was leaving, the hug they shared was longer than usual. Shortly after Juan’s death, Diego learned that his brother and his sister-in-law were going to have a child together. The first baby of the family.

“[Juan] wouldn’t want me to be miserable. Heck, if I would’ve been the one that passed away, I definitely wouldn’t want him to be miserable,” Diego says. “So, I don’t know, I just remember him for who he was and actually live my life like always.”

In the newsroom he created similar friendships. He always stayed late working on stories or helping colleagues with their homework for a professor he’d coincidentally taken in the past.

At home he had similar work habits. His normally loud and lively house only sat quiet while Juan worked alone in his room for hours. His lone companion was Emi the chihuahua who would curl up beside him and take breaks from her naps when Juan took breaks from work, yet Kobe was the one who enjoyed the spotlight making multiple appearances during classes over Zoom.

Following his death, Juan’s work continued to win awards, co-placing first for “Best News Series” at the annual Journalism Association of Community Colleges awards for his coverage of a missing student who was later found dead. A scholarship was later started at ECC under Juan’s name and currently sits at $1,000 which will be awarded to one or more journalism students at the end of the spring semester.

Rosemary first met Juan on October 22 while on assignment. She was a photography student at ECC and was there to take photos of a cultural event during Hispanic Heritage month which Juan was writing a review about. It was an enjoyable experience for the both of them, Rosemary recalls. They arrived early and left late following true journalistic standards, striking up conversations with everyone at the event.

He made her feel comfortable, Rosemary says. Juan charmed everyone present and was able to spark intimate conversations with attendees and performers on everything from their mental struggles to their religious ideologies. There was no other reporter who could get people to open up as Juan could, Rosemary assured. It was a skill unique to him, something she could never do herself.

“That was just Juan. He could talk to everybody, and everybody wanted to talk to him,” Rosemary says with a smile.

She pulled the collar of her grey shirt over her lips and then seemed to forget herself in expressive bursts of excitement as she sat in her car. Moments of silence brought tears to her eyes as she quietly remembered Juan, though she spoke of him as if he were still present.

There Juan met a student with skills ranging from music, literature and science. He’d later write a profile piece about her, one which would earn him much attention from his editors.

“I remember that piece, that piece was beautiful,” Rosemary says. “I think that’s when everyone was really like ‘wow, Juan is a great writer.’ This is when everyone was like, fighting. All the editors were fighting; ‘oh, I want Juan on this, oh I’m gonna get Juan on this’.”

When the bulk of editors that semester graduated, Rosemary remembers much tension at the question of who would lead Warrior Life magazine next. She knew the magazine would be in good hands once Juan applied for the position. All the former editors were, she recalls.

She found out about Juan’s death through former news editor Fernando Haro, who messaged their old editor’s group chat on Snapchat and urged them to join a video call. Rosemary said they sat there in silence for several minutes slipping between not believing what they were hearing and shock.

“We weren’t ever really serious around each other,” Rosemary says. “I don’t know, I think I started caring for [Juan] instantly. He’s just one of those people you just wanna see do the greatest things.”

The group had decided they wanted to gather in Juan’s memory, but Rosemary felt it wouldn’t be right to gather and not tell Juan’s family. The short gettogether then turned into a memorial at Kenneth Hahn Park where family and friends were invited. Old colleagues of Juan stepped forward to share how he’d changed them. They shared stories of the humanitarian values he instilled onto his work and his gentle character as a person.

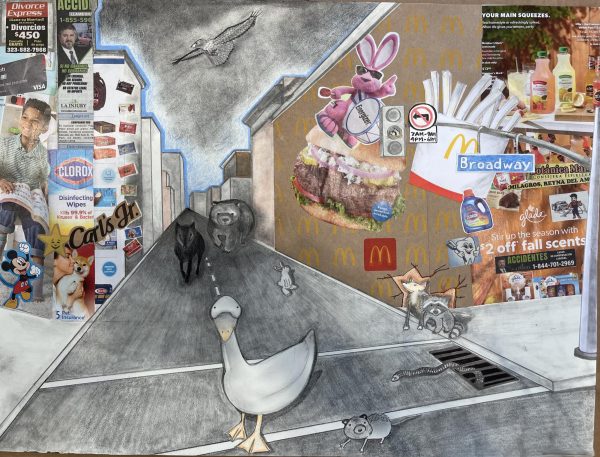

During his time at ECC, Juan wrote stories which centered the community. From homeless encampments to an aspiring scientist, a tragic series covering the murder of a student and a personal column in which he revealed his own history with mental struggles.

“I always felt that I suffered from a mental disorder, and I thought it could be something I could overcome alone and in silence because I come from a traditional, old-school Mexican family,” Juan wrote.

His brother Jose read the first half of the column when it was posted but didn’t finish it until after Juan’s death.

“When I read it, I shed some tears because you know, you always see someone working hard but you don’t see the effort or you don’t see some of the struggles [that] are behind another human being,” Jose says. “Especially us as Hispanics, it’s kinda hard to vent with a person because, how he said, we come from an ‘old school family’ where we kinda had to say ‘suck it up’ or you get over it instead of facing the problems.”

Jose recalls his brother always wanted to be a teacher for English learning or first-generation students. He believes Juan kept his switch to a journalism major a secret from his parents out of fear they would not understand his decision.

At his memorial his mom revealed she had come to discover his change in major and admitted being scared it would lead her son down a dangerous path but Juan consoled her, she said. He assured her he wanted to be a writer and he would be working at a desk where he would be safe from the dangers his mom wanted to keep him away from.

When the doors of Inglewood’s mortuary building opened, a white casket adorned with gold peeked from the other side. The service was held in the parking lot due to COVID-19 restrictions with the forum overlooking his family’s prayers. He was buried to the sound of his uncle playing guitar and the crippling cries of his mother dressed in white repeatedly asking herself why her son had died if she had loved him so much and he was her youngest.

Showered in flowers from friends and family, Juan was lowered into his grave and the earth pounded into place above him. Tufts of grass were laid atop the brown dirt and watered so they may take root easier and mend the grass bed in time.

A legend, an inspiration and a young talent.

His grave now stands as a scar which heals itself but remains.