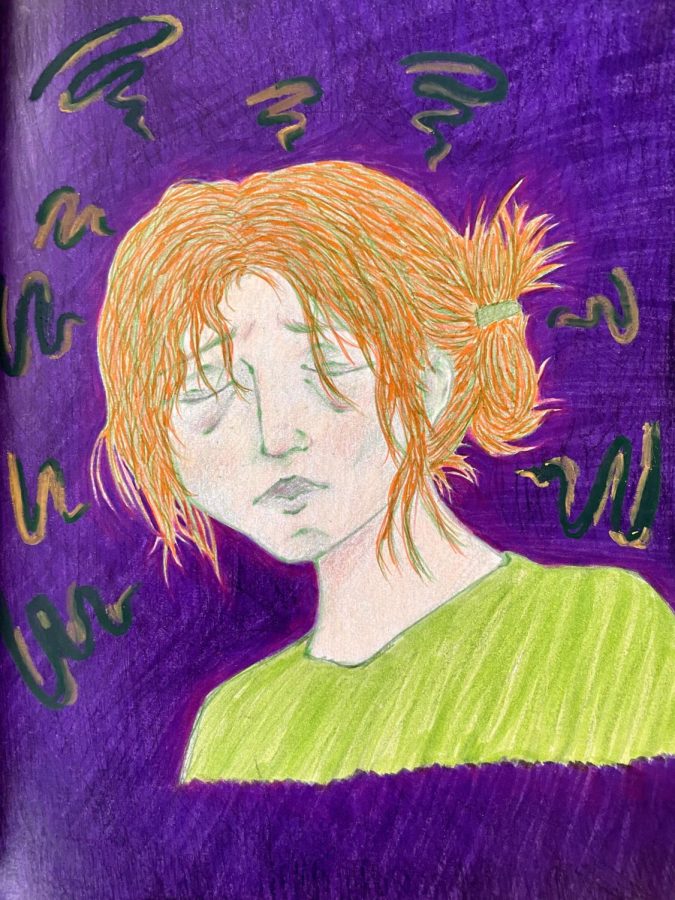

My green monster, OCD: How my OCD has affected my daily life

Despite knowing the response that awaits me, I tried to break through the barriers that have surrounded me since I was a child.

“I can’t walk.”

Although the words that are uttered out of my mouth hold truth, the fact that I was diagnosed with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) makes people doubt that any fear I have can be a reality.

The disorder creates excessive thoughts and fears (obsessions), and has the person perform certain rituals to ease those repeated thoughts (compulsions). The obsessions are notorious for making the person feel that the fears are real and dangerous, but are seen as irrational to anyone without OCD.

As usual, I see disbelief written on their faces.

“Let’s just put on some muscle relief cream.”

My 19-year-old body knew that wouldn’t fix the problem. Muscle relief cream was not going to fix the fact that I had fallen off a skateboard when riding down a hill by my grandmother’s house in Palm Springs. However, growing up being told that my OCD overexaggerated everything and my fears were not realistic made me doubt the physical pain I was feeling.

Hearing the same responses of my fears being wrong and I am “crazy” has made me doubt myself in knowing what is true or not.

I agreed to put on the white muscle relief cream.

An hour after the cream was spread on my body, still being unable to walk and crying every time an inch of my body moved, my grandma took me to the hospital.

I had broken a part of my tailbone and pelvis.

Being diagnosed with OCD by my therapist in the fifth grade came with a hefty price.

It’s hard for a child to understand that something about their brain is different from other people. Therefore, my therapist read me the book “What to Do When Your Brain Gets Stuck,” which explained what OCD is and the coping mechanisms to combat OCD for children.

One of the chapters was to give OCD a form, a monster that lives in your head that tells you repeated thoughts and orders you around. This showed me that my OCD thoughts are not mine and helped me distinguish my personal thoughts versus what my disorder makes me think.

A little green monster, round and fuzzy, with a mean expression on its face — that’s what my OCD looks like.

The book also showed me how to lessen the powers of OCD. A favorite tool I learned was doing the opposite of whatever compulsion OCD wants me to perform.

Walking along the sidewalk on the Las Vegas Strip at 19 years old, I see roadkill on the road next to me.

“What if the germs from the roadkill got on your hands? What if the wind carried the germs to your hands? You have to wash your hands otherwise the bacteria will continue to grow and get into your fingernails and you’ll get worms and you’ll get sick,” OCD repeats into my head until it is hard to hear my own thoughts.

Feeling overwhelmed as my mind races about the possible germs that now live on my hand because of the roadkill, realization hits me that I should do the opposite of wanting to wash my hands.

I lick both my hands.

The fears go silent. OCD goes silent.

Doing the opposite of an OCD compulsion is very extreme and the idea can be very nerve racking for people with OCD. The reason why I am able to do it more easily now as an adult is because of the fact I started learning the coping mechanisms and how to challenge the debilitating fears of OCD as a child.

However, combating OCD on a normal basis is not always so simple as “doing the opposite of a compulsion.”

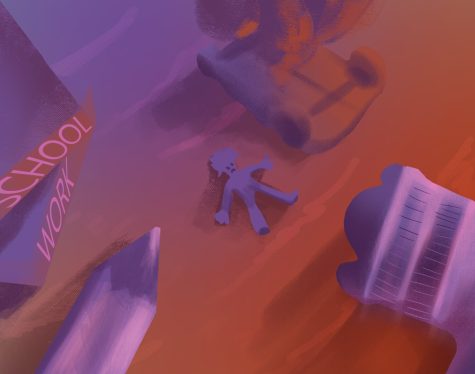

This was especially true during my junior year at San Pedro High School, when my OCD fears of being watched and murdered as I slept festered. It grew to the point where I could not close my eyes at night without quickly opening them in fear that someone or something would be standing in front of me.

5-8 p.m.

Those were the times I was able to fully sleep on weekdays. From 5-8 p.m. were my safe hours to sleep. It was after school, homework, dinner, but before everyone in my house would be asleep.

Weekends were slightly better because there was more availability to sleep throughout the day. Although there would still be sly remarks about how “lazy” and “what a teenager” I was.

My therapy schedule changed from once a week to twice a week to try to get a hold of a good technique and control this OCD “flare-up” – a term my therapist and I use when my OCD peaks, but then drops back down to normal after finding a good coping mechanism.

But this flare-up seemed to never go back down.

Months and months of little to no sleep and all nighters, constant anxiety began to creep into the day instead of just at night.

Hallucinations from the lack of sleep began to plague me wherever I went. The hallucinations only fueled my paranoia of someone watching my every move.

There, a 6-foot shadow of a man stood across the room from me. Despite the fact he had no eyes, I could tell he could see me. His legs inched closer to where I laid on the couch. Frozen in fear, I was afraid to blink. To breathe.

He disappears.

Combating these fears with my usual “do the opposite” tactic was too difficult. The failure of not being able to fight these OCD thoughts, as well as the lack of sleep, made my mental health decline fast.

Towards the middle of my second semester of my junior year, I was admitted to local hospital due to my active suicidal ideations.

Staying for four days in the mental hospital both helped and hindered my mental well-being.

The nurses and staff were rude and unprofessional as they did not care if the patients would eat or not and would always choose to administer a “sleep juice” shot if a patient was getting overly emotional. To this day, I do not know what was in the shot. But the other patients and I were very afraid of the “sleep juice” because it would knock the recipient out cold as soon as the nurse administered it.

Although there were major problems with the hospital, it was the first place I was able to sleep peacefully.

My OCD is slow and can not come up with new fears in a new environment. In the hospital, there were no fears of shadows watching me or something getting me in my sleep.

Finally being able to sleep helped me reground and reevaluate my next steps on how I can try to get a peaceful night’s sleep at home.

Since then, I am still combating my OCD flare-ups but I am progressing in how I handle and view my OCD. A huge help with understanding my OCD and not feeling isolated with those thoughts has been the growing awareness around mental health and how people are being more open about their OCD experiences.

With 1.2% of adults in the United States of America being diagnosed with OCD, according to the National Institute of Mental Health, it is important for people with OCD to be represented and heard.

If you or someone you know is struggling with OCD or mental health, El Camino College students receive a free resource called TimelyCare. It provides 24/7 mental health care and allows students to schedule appointments with the therapist of their choice for free.

I have a right to be heard and not shamed for my disability because it will always be a part of me. OCD can be a lot to handle, but I have hope that my coping mechanisms get stronger with practice, and the people I surround myself with give me the correct support I need to grow.

Editor’s Note:

- Story was updated and alignment of illustration was changed on Friday, June 16.