I suffered a personal tragedy. Now, I work for the news covering other people’s tragedies

It’s just after 2 a.m. in September 2022. A city bus has crashed into three other cars in Willowbrook, sending a work van into a crowd of people gathered at a taco stand. First responders radio in that one person is dead underneath the van, and others are hurt.

Hearing this over a police scanner while I waited in a parking lot near the 110 and 105 Freeways, I start my car and head to the scene. I park, get out, set my camera up and begin taping the aftermath of what is to turn into morning’s big news story.

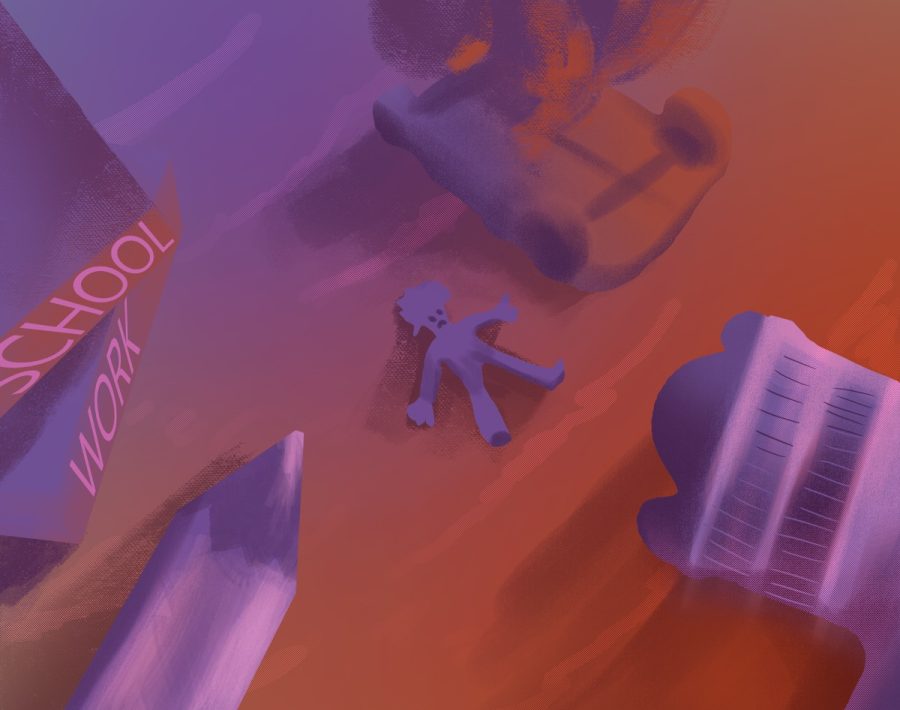

I am a freelance news photographer, known in the media industry as a stringer. I mainly shoot crime and tragedy, as that is what makes the most money. Doing this kind of work, you typically see things that most people both have never seen, and never want to see: death, carnage, the aftermath of violence and grieving loved ones.

Working in the news business, you must separate your emotions from your work, as you deal with a lot of the bad news. Otherwise, for some, you will just never be able to go a day without having a breakdown.

However, I noticed something. I don’t feel much of anything.

When I go home for the night, I don’t sit and think about what I just saw, reflecting off of it and changing my life for the better. The only thing I change are my clothes and then I go to bed.

How I deal with death and tragedy may have something to do with my mom. When I was 12 years old and still in middle school, my mom was diagnosed with a rare form of cancer.

She had been feeling the effects of it for years at this point and only got it diagnosed when the symptoms got worse. The doctors said it was already at Stage IV and terminal.

She died a year later, about a week after going to the Philippines to be with her family during her final days.

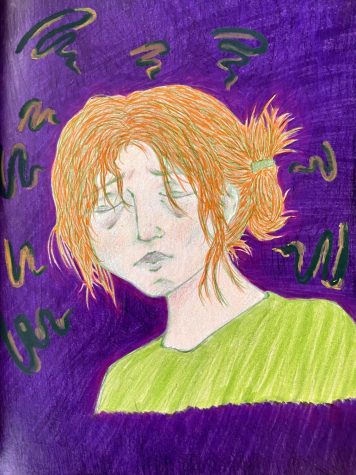

When I got the call in the morning from my family in the Philippines, I was 13 years old. It was devastating – no child should ever lose a parent in this manner. For weeks, I grieved. I was pulled out of school to attend Mass for her, which in my 13-year-old brain, only made things worse. Why make me relive how I felt the day I got the call that she had passed?

Once the initial shock and grieving passed, I felt like nothing mattered. I stopped caring about my classwork and my grades plummeted. The only thing that kept me afloat during my years in middle school was the marching band, which kept some order in my life to keep going, but was not enough to fix my problems.

I never sought help for how I felt. Things were different 10 years ago, as mental health was not as much of a societal focus then as it is today. At the time it seemed shameful to need to go talk with someone about how I was feeling.

I was not the only one who felt the same about mental health. Two surveys conducted by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, a US government agency, found that in the past decade, there was almost a 60% jump in mental health service usage by youths age 12 through 17, with only 2.9 million seeking help in 2010, before rising up to 4.6 million in 2020.

While mental health service usage has increased, I did not think about these kinds of services at the time.

A curiosity about journalism, combined with the lack of reaction to death led to me becoming a crime reporter and photographer for a local newspaper while in high school.

Eventually, I grew numb to the feeling of sadness over my mom’s death and told myself that I’ve gotten over it and moved on with my life.

I am not completely desensitized to tragedy, however. A teenager was riding in the back of a pickup truck in San Pedro. The truck suddenly sped up, throwing the boy out the back and slamming his head on the pavement. He was rushed to a trauma center, where he later died.

As I recorded the scene, a man drove up. He asked what happened and I casually stated that a kid hit his head after an accident. He then said he was the godfather and if the kid was alright.

It pained me to be the one to tell him that his godson died at the hospital.

He sped away, grief-stricken. I realized this wasn’t just some person who died in a crash. It was someone’s son, someone’s friend, someone’s teammate. My lack of reaction to death, looking back now, was my own twisted way of “mental health treatment,” by just not thinking about it. The interaction with the man broke through that way of thinking.

The family held a vigil for him where the accident occurred and hung a banner with his photo onto a chain link fence. I pass by that banner every day.

Mental health is a topic that deserves to be in today’s societal spotlight. It would have done me a lot of good had I used whatever services were available at the time to help cope with my mom’s death.

While I will be forever affected by her death, I will simply use it to keep growing.

—

Mental health resources are available to El Camino College students in need. ECC Student Health Services offers free mental health support for students currently enrolled in classes.

They can be accessed in-person at the ECC Student Health Center, open Monday: 8 a.m. to 7 p.m., Tuesday-Thursday: 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., Friday: 8 a.m. to 1 p.m.

Student Health Services can also be contacted through their number at 310-660-3643.

Students can also call the ECC After-Hours Emotional Crisis Line at 310-660-3377.

Anyone suffering a mental health emergency can call or text the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 988.

Editor’s Note:

- Illustration was enlarged on Sunday, June 11.