Finding resilience in the face of tragedy: Reflections on the Passover Seder

Very often, Jewish holidays celebrate the times when we did not die.

Close calls with utter devastation have been a heavy part of the Jewish experience since the beginning of time.

But there is also another story of the Jewish people—resiliency

Where fear meets faith is part of many Jewish holidays including Purim, which celebrates the close call with death in ancient Persia, as well as the Hanukkah revolt against the Romans in the first century B.C.

Another example is the Passover Seder, which this year is the evening of April 5. This is when Jewish families recline in their seats, a seating position which has meaning: In ancient times a person who reclined at a meal was a free person.

At this meal, the youngest child is charged with asking one of the four questions that kick off the holiday which recites our exodus from ancient Egypt after generations of bondage.

“Why is this night different from all the other nights?” I once asked as a young boy.

While Passover reminds me of matzah ball soup and matzah pizzas, I am also reminded of the dark period in our long history as Jews around 80 years ago.

The rise of Nazi Europe and the subsequent extermination of approximately 6 million of its Jews left a stain on what it meant to be so-called delivered by God.

From the Torah, I was told: “For not only one [enemy] has risen up against us to destroy us, but in every generation, they rise up to destroy us. But the Holy One, Blessed be He, delivers us from their hands.”

“Where was He?” I thought. Where was God’s intervention when over and over again they rose against us and we faced our demise? And why do I recite something that often feels untrue?

While any person of faith knows it is hard to reach an agreement when you question your own beliefs, faith lies in the courage to ask such questions.

I am not generally one to question God. However, I researched these questions in the hope of finding what, to me, would be a sufficient enough, long-lasting answer.

Initially, I stumbled upon an explanation from the Midrash—ancient rabbinic commentaries of the Hebrew scriptures. The earliest of which comes from the second century A.D., after the devastation of an empire following a series of divine plagues when Israelites left Egypt.

The Hebrews found themselves stuck between the raging waters of the Sea of Reeds on one side and the vindictive pharaoh’s army on the other.

They were faced with a choice between which way they wanted to die.

God told Moses, the leader of the Israelites, to take his people into the sea.

The Israelites naturally hesitated at such a command.

However, one man, Moses’ brother-in-law, Nahshon, took matters into his own hands and walked into the sea. Step by step, Nahshon moved further into the sea until the water reached just below his nose.

Moses supplicated with God to help the Israelites and was told to raise his staff and spread his hands over the sea, dividing the waters and revealing a path to safety.

While this specific case sounds like the happy ending from the DreamWorks animated movie “The Prince of Egypt,” the Hebrews wandered for four decades because they worshipped an idol in the form of a golden calf.

But in the end, they made it to the promised land.

That takes me back to the Holocaust during a point in time when Jews took up arms against their oppressors: the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of 1943.

On the eve of Passover on April 19, the Jews of the Warsaw Ghetto resisted a vastly superior enemy to prevent the liquidation of the ghetto. They held out resistance for a staggering 27 days.

This last-ditch act of resistance garnered nothing more than death and the deportation of the remaining Jews of the ghetto to forced labor and death camps where the majority would perish.

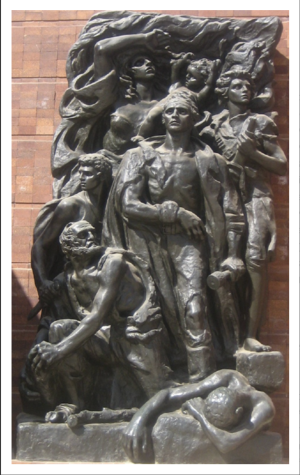

From that, I was reminded of a monument I visited during a trip to Poland in 2020.

Created by Nathan Rapoport in 1948, and originally erected amidst the ruins of the Warsaw Ghetto, the monument portrays two sides of the Holocaust.

One side bears the faces of the helpless heads and shoulders bowed as they shuffled to the slaughterhouse of the death camps. The other shows eight figures taking up arms despite their visible wounds to the bitter end.

I was drawn to the second side, depicting the final act of resistance before demise.

Like Nahshon’s first step forward in an act of faithful courage, those in the Warsaw Ghetto chose to take fate into their own hands.

Without a doubt, the ending to the uprising was grim, but the history of the Jewish people, as our past experiences show, prevailed.

Three years after the end of the Holocaust the Jewish state was re-established after 2,000 years.

At difficult times in my own life, I am reminded by the stories of Nahshon and those who died in the uprising that sometimes God’s actions are hidden.

It perhaps was best said by Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion: “In Israel, in order to be a realist you must believe in miracles.”

During the darkest of times, the first step of faith is needed, and then God will deliver us to our promised land.