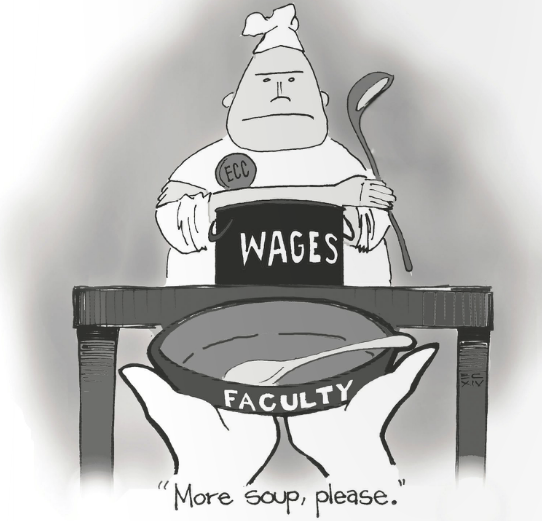

Editorial: May we have some more?

Since 2008, faculty and classified employees at EC have not received any raises to adjust for the steady climb of inflation.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, in this same six-year period, the Consumer Price Index (CPI), a measure of change in the prices paid by urban consumers for a “basket” of goods and services, increased by 10.9 percent.

Translation? EC employees effectively earn 10 percent less (relative to the things they want and need to buy) compared to their 2008 selves.

For an institution filled with so many talented educators and tireless workers, that reality is both tragic and in dire need of remedy.

The EC District is currently proposing a raise spaced across three years to its employees: 1.5, 1.7, and 1.8 percent respectively per year.

Such a proposal would offer a long-overdue raise, but one incapable of restoring the purchasing power of EC’s employees for even half of what they’ve lost these past six years. Meanwhile, such a deal also carves out another three-year block where their salaries are locked in, regardless of changes in real-world circumstances, and to their disadvantage when their full contract is up for renegotiation in 2015.

The District’s motivation for tabling such numbers is associated with the Cost-of-Living Adjustments (COLA) it expects to see from the state of California.

Dispensing raises leashed to this metric, however, is damaging to the financial situation of EC’s faculty and classified employees.

There is no direct correlation between increases in the Consumer Price Index (which measures changes in actual market prices) and the state’s COLA allowances.

From 1985 to 1991, California actually offered COLAs at higher rates than the increase in CPI (29.4 percent and 27.6 percent respectively). Any benefits workers might have garnered from this, however, would have been outweighed the following four years when the state offered no COLA increase despite an 8.6 percent rise in prices.

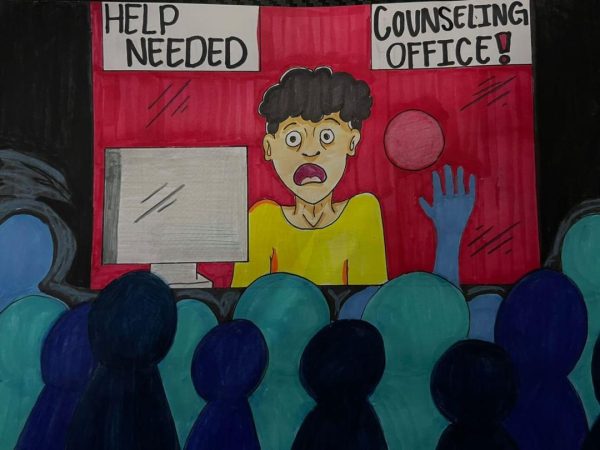

Additionally, this sort of lag between what employees need and what they make may very well be a disservice to their performance as well.

The impact of financial stresses upon a student’s performance in the classroom is well documented by social scientists across the nation. Can you fairly expect a student who constantly worries about their bank account to outperform one unfettered by such concerns? How about a teacher?

Arguments linking financial security and achievement are gaining traction, perhaps most notably, from studying successful companies in the private sector.

According to a recent article published in the Harvard Business Review titled “A Minimum-Wage Hike Could Help Employers, Too,” companies that invested heavily in their workers were often “growing and coming out on top in very competitive industries.” On the other hand, jobs with subpar wages, “were not just rotten for the employees but were hurting the companies.”

While EC isn’t tied to profits like private companies are, the same principles behind motivating workers and assuaging their financial worries (in return for markedly better performance) apply.

The District has demonstrated that it’s not wholly opposed to significant raises despite tough economic times: EC’s board of trustees offered President Fallo a $40,000 raise last year.

According to a Daily Breeze article titled “El Camino College expected to offer Thomas Fallo raise to stay as president” from January of last year, the move “boost[ed] Fallo’s base pay from the current $277,000 to $313,000,” as well as providing him with a “5 percent increase for each of the next three years, ultimately bringing Fallo’s salary to $362,000 by February 2016.”

While someone like Fallo is objectively crucial to EC’s ability to function, aren’t its faculty and classified employees? The district’s willingness to offer the former a 5 percent raise, repeated across three years, while remaining resistant to even a singular, 6 percent raise for employees that have been making less and less since 2008, reeks of iniquity.