Living as an undocumented student under the Trump administration

When Carlos Paz was a toddler, his father left the family in Guatemala to escape poverty and violence, establishing himself in the U.S. through a series of low-wage jobs.

Paz remembers asking his mother where his father was, only to be told made-up stories that left him yearning for his presence.

He would not see his father again for two years.

It was 2004 and his father saved enough money to pay for a “coyote” that would help smuggle his family across the U.S.-Mexico border.

Smuggler’s helped 5-year-old Paz and his mother travel 2,600 miles from one of the most dangerous areas in Guatemala City, known as Zone 7, to San Diego—where Paz would be reunited with his father.

Throughout the journey, they risked being detained by border patrol.

If they were caught, Paz and his mother would be deported and have to start the journey all over again, increasing the risk of running into assailants, being killed by a stranger or dying of dehydration in a remote borderland.

But during the two-day journey across three countries, Paz’s main concern was his mother’s safety.

“I didn’t have the strength of a man,” Paz said. “There was a lot of people that you don’t know and people can hurt you along the way.”

Two years after arriving in San Diego, Paz moved to Los Angeles where he was consumed by the city he had only seen in movies. As the excitement wore down, the daunting fear of going to school still outweighed a new start in a new city.

Paz said he had trouble learning his ABC’s and the English language but through the help of his classmates and the English as a Second Language (ESL) program at Vermont Elementary School, he felt like he was raised in the U.S.

He assimilated to the culture and was accepted by his classmates.

It wasn’t until he attended El Camino College, and applied for the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), the California Dream Act and AB540 that he felt labeled being in several programs just because of his legal status.

DACA is a federal program that grants undocumented people, as young as 15 protection, from deportation for two years and gives them work authorization, Arlin Gonzalez, advisor at the California State University, Dominguez Hills (CSUDH) Toros Dreamers Succes Center or Dream Center, said. DACA is unrelated to AB540, a tuition equity law that grants in-state tuition, and The California Dream Act, she added.

“[Undocumented] students don’t understand the difference between their peers and them until college because they started getting restricted unlike their citizen peers,” Gonzalez said. “Counselors don’t know how to help [students that] weren’t eligible because they didn’t have Social Security.”

Students as early as high school seniors are encouraged to apply for the Free Application for Federal Student Aid. (FAFSA) but must have a Social Security number to do so.

Undocumented students do not have a Social Security number thus making students like Paz, ineligible for free federal money.

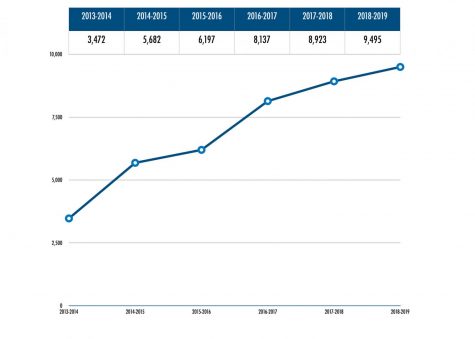

However, in 2018, Paz was one of 9,495 undocumented students in the California community college system that applied for the California Dream Act Application, according to a 2018-2019 report by the California Student Aid Commission (CSAC), an agency responsible for the administration of financial aid programs for higher education schools in California.

The California Dream Act provides undocumented students or “dreamers” with state-funded grants since they are ineligible for FAFSA, according to CSAC.

Since 2014, the number of undocumented students who applied for the Dream Act increased by 6,023 or 36.57%, according to a 2013-2014 report by CSAC.

Despite there being support, these students are at risk of deportation following President Donald Trump’s 2017 Executive Order: Enhancing Public Safety in the Interiors the United States, where he expanded the definition of who’s a priority for deportation, according to a 2017 report by the White House.

“That’s what I’m afraid of,” Paz, who is now a 21-year-old fire science major, said. “All those hours and sleepless nights [studying], it’s gone just like that.”

In 2017, Trump and his administration attempted to end the DACA program, according to a 2017 report by the White House.

This put 89,900 DACA applicants in the greater LA area including Paz, at risk for deportation, according to a 2017 report by the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

“I was waiting at [my front] door like ‘when are [Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)] gonna come out and say ‘let’s go?’” Paz said.

But Trump’s attempt to end DACA was blocked by several states, including California.

Undocumented students in community colleges

Due to Trump inducing fear among the undocumented population, students are afraid to share their status in fear that they might be targeted or deported, Gonzalez said.

Several undocumented students won’t apply to government programs, including the Dream Act as they are afraid to have their names on any government document, Gonzalez said.

Gonzalez said this creates difficulties in narrowing down specific numbers, limiting the data about undocumented students from each community.

The Union looked at the citizenship status of students from community colleges in the LA area including Cerritos, Chaffey, Fullerton and LA Pierce College, through the California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office Management Information Systems Data Mart.

The Data Mart is a community college online database, which, under one of its categories, classifies student’s citizenship status in seven sections—U.S. citizens, permanent residents, temporary residents, refugee/asylee, student visa, other and status unknown/Uncollected.

The section “other” and “status unknown” includes but is not limited to undocumented students as the definitions provided for the other five sections by the Data Mart do not pertain, meaning the specific numbers for each community college are not available to the public.

Jaime Gallegos, First Year Experience (FYE) counselor at EC, said data for undocumented students is often non-specific as a way to protect them.

Regardless of the numbers, Gallegos said the programs at El Camino provide resources for undocumented students including ally training workshops for EC staff and high school counselors as a way to raise awareness of student needs.

“Obviously, there’s been a huge sense of fear,” Gallegos said. “When you have someone in office that like creates that kind of fear, of course, students are going to wonder what their future is going to look like.”

During the fall and spring 2018 semesters, EC’s undocumented students made up less than 2.90% of the total student population, a drop of more than 1% from fall and spring 2014 when it was closer to 4%, according to the Data Mart.

LA Pierce College experienced a similar drop from fall 2014 to 2018 when undocumented students made up less than 3.89% of the student population, decreasing by 0.69% to 3.20%, according to the Data Mart.

Gallegos said there are several reasons why the numbers are these community colleges are decreasing, including, but not limited to, undocumented students who begin to question whether getting an education is in their best interest because if DACA gets rescinded then they will not have the opportunity to work—thus potentially dropping out.

Unlike Cerritos College, whose student government offers undocumented students access to an immigration lawyer through their budget, Gallegos said students at EC are referred to immigration lawyer and EC English professor Jeffrey Jung.

Jung, who has been at EC for 20 years said undocumented students were not referred to him until the Trump was elected president in 2016.

“There was a lot of fear and panic,” Jung said. “People thought they’d be arrested. [But] fear and panic are always ahead of reality.”

Jung said he talks to students that are referred to him but everyone wants their case to be pro bono or free of charge.

“When it comes to pro bono, everyone wants it but there are some cases that are life and death,” Jung said. “All students may think they fit the parameters but we also have people who someone is trying to kill them in their country or their spouse set them on fire.”

Instead, Jung said he speaks with referred students about their case and provides them with information.

Jung added that although fear prevents several undocumented students from applying and getting into a program’s system, Trump’s fear-mongering has motivated more people to apply for protection.

But still, undocumented students can feel like second-class citizens, Jung said. This can increase their level of conformity where they don’t feel like progressing in life if they can be deported, he added.

Gallegos added that because undocumented students might have that underlying fear and instability, allies work closely to provide them with resources and connect them with various legal assistance.

Compared to EC, undocumented students at Cerritos College made up less than 6.03% and 5.35% of the student population in fall and spring 2018 respectively, 1% more, according to the Data Mart.

Similar to EC, there was a smaller decrease in the possible undocumented student population of less than 0.25% between fall 2014 and 2018.

Cerritos experienced a large decrease between the spring 2014 and 2018 when there was a less than 1.30% drop in the undocumented student population, according to the Data Mart.

Lynn Wang, financial aid counselor and DREAM Club co-advisor at Cerritos College, said students and staff at Cerritos started preparing to help undocumented students prior to the 2016 presidential election.

After the election, affinity groups were hosted at several colleges, Wang said, including Cerritos College, Chaffey and EC, where students who identified as undocumented were able to connect with allies who could talk them through emotions or concerns.

However, Wang said that because there is no one way to track who is an undocumented student, besides seeing who submits the Dream Act application, it is difficult to understand each student’s necessities, considering some students’ needs may be different depending on their ethnicity.

“This doesn’t have to be the only thing they identify with, they could also be LGBT,” Wang said. “I think it’s one thing to say as a college that you believe in diversity but provide no financial support or assistance to help that flourish.”

Of the five community colleges reviewed by The Union, only Chaffey and Fullerton College had an increase, according to the Data Mart. Both colleges had an increase of no more than 0.25% between fall 2014 and 2018, according to the Data Mart.

The increase at Chaffey College can be credited to community awareness, prompting the opening of the Center for Culture and Social Justice, a “safe-haven” for all students, Neil Watkins, Dreamers Club faculty advisor and English professor, said.

Gonzalez, who has been working with undocumented students at several colleges and universities, including Long Beach City and USC said that for a long time and even now, several institutions do not have Dream Centers established like CSUDH that can provide students with resources, including a safe space to talk about their status.

Gonzalez said she was inspired to work with undocumented students because she comes from an undocumented background where her parents were scared to share their status.

“At a very young age I knew that it was wrong that the media would target our community as certain things and creating stereotypes about undocumented people being this and that,” Gonzalez said.

Like her parents, there are students who are afraid to speak up or share their status to get resources in fear of feeding misconceptions or stereotypes, Gonzalez said.

Because of this, student and community organizations took it upon themselves to provide undocumented students with resources, including funds for DACA renewals, Gonzalez said.

However, Gonzalez said funds are running out for these organizations as there are too many students in need, continuing the burden for students including Paz who have to pay for the $495 DACA renewal every two years or risk losing their status.

“[It’s] time to get creative and looking into other ways to pay the fees,” Gonzalez said. “Before Dream Centers, students were still going to college and funding their own education.”

Life as an undocumented student

Gonzalez said people tend to feel sympathy towards the obscurity undocumented students feel on a campus full of new people.

“Pobrecitos,” Gonzalez said she often hears.

Poor little ones.

But Paz doesn’t feel sorry for himself, he says as he sits at the kitchen table in the small LA home he shares with his two younger siblings and parents.

After a long day taking Emergency Medical Technician classes (EMT) at EC and a shift as a mechanic at an auto body shop in Santa Monica where he works with his father, he is enticed by the smells of carne asada and chopped onions that fill the busy room.

As everyone waits for dinner, his sky-blue parakeet, named Blu, slides down an evergreen-colored curtain and squawks at Paz as she perches on his weary shoulders.

“I’m proud of who I am,” Paz said. “Just because I come from poverty doesn’t mean I’m nothing.”

However, Paz lives in fear that Trump’s next move will be the one that sends him back to Guatemala City, a place he hasn’t been to in 15 years.

“I wouldn’t even last a day or two,” Paz said. “I don’t know the streets. I could end up in a bad neighborhood and that’s it for me.”

Trump has said that Mexicans are rapist, criminals and that immigrants are animals.

But Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist for her work on immigration Sonia Nazario condemned his actions and comments for the inaccurate depiction.

In her career, Nazario has gone in depth to cover the stories of immigrants seeking a better life in the US.

“For a long time [undocumented students] could get a job in the above-ground economy,” Nazario said. “That’s the problem increasingly. Now they are facing the prospect of having to work in the underground economy.”

The underground economy includes jobs that pay workers in cash and require no government documentation to get hired, meaning the money goes untaxed.

Paz, who is training to be a firefighter, was denied his dream job of being an army medic last semester due to his DACA status, making him wonder if his status will get in the way of his career again.

“It feels like a waste of time,” Paz said. “How am I going to reach my dream or goals if someone is not going to let it happen because we’re different from everyone else?”

Jung said undocumented students like Paz can apply for citizenship by marrying a U.S. citizen.

By marrying a citizen, Paz can apply for a green card and three to five years later and become a citizen himself, Jung said.

But at 21, Paz said he is not looking to get married yet, leaving him at risk until then.

Not taking opportunities for granted

Paz eats his dinner outside alongside his mother and father while his siblings take their plates into the living room.

He reminisces about life in Guatemala where students are not offered lunches in grade school like Paz was given at Vermont Elementary School.

He remembers his grandma’s phone calls, telling him about the teenagers she saw stealing and killing on the streets instead of getting an education.

“Some people don’t understand the struggle,” Paz said. “They’re not grateful.”

That’s why his father emphasizes the importance of school to his children so that they don’t struggle later in life.

Paz listens.

He said he tries to stay on a straight path at EC while balancing work and social life, avoiding all trouble as it could mean losing his DACA status.

“Once [DACA] continued it gave me hope,” Paz said. “I can do this. I can achieve my goals.”

But for now, his eyes red and drooping from exhaustion, Paz is only thinking about studying for his next EMT class.