Visiting the Triangle Factory Fire a century later

In 1911, a roaring fire devoured the lives of 146 women, and the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory became their coffin.

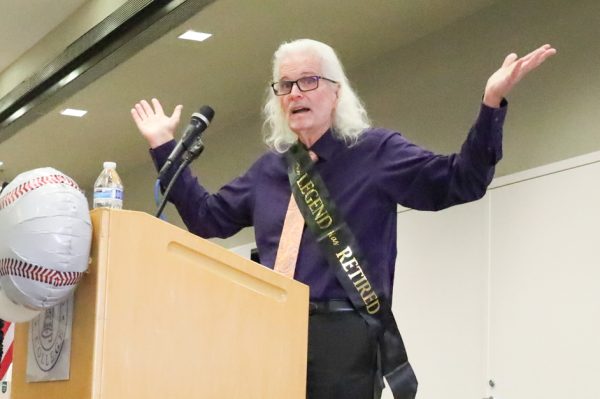

This tragic-yet-pivotal event birthed important 20th century social and economic changes. So for Women’s History Month, Sue Dowden, sociology professor, organized a showing of the documentary “Triangle Fire“ on March 25 in hopes of teaching EC students about the event’s significance.

“If we forget history, it’s bound to repeat itself,” Dowden said.

This documentary directed attention towards gender inequality 100 years ago. It demonstrated that the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory owners’ concerns dealt chiefly with profits and not on the safety of their women workers.

“[The owners] spent a lot of money to stop them from unionizing. To stop the women from [getting] their voice heard,” Luukia Smith, president of the El Camino Classified Employees, said, speaking on behalf of union workers after the film.

This exploited them as both women and employees, she added.

Viewers couldn’t help but to be reminded of stark parallels between the 1910s and now.

“I started thinking about the comparisons. I didn’t really feel empowered. I felt depressed [because of] the similarities between what happened 100 years ago and what’s happening now,” Sarah Musnicky, 21, English major, and a member of the panel that helped organize the documentary showing, said.

According to “Triangle Fire,” the women workers, on the cusp of social change, unionized in attempt to do away with horrendous and unfair working conditions: 14 hour work shifts, a daily pay of $2 or less, and an expectation to sew 3,000 stitches each minute.

Workers would often have to pay for their mistakes, electricity, and thread.

“That’s wrong. [If] they go home with no money, they are starving their family,” Laquisha Radford, 26, sociology major and attendee, said.

Despite the plummet in morale immediately after the tragedy, a strong middle class emerged as a result of the consequent reform.

“This history is very important and if we can show it to your generation today, maybe they will understand what it takes to do what those people did,” Dowden said, “to make it a better workplace.”

Modern-day unsafe workplaces, mines for example, still bother Smith. As of 2000, there are still an estimated 255,000 sweatshop workers in the U.S.

“Some of this still goes on today, even though we have laws,” she said. “The government agency that is supposed to be monitoring [safety has] been cut. So they don’t have enough inspectors to go around and check. That’s where unions come in to be the watchdogs.”

The number of unions is decreasing, however, which takes power away from the workers, according to Dowden.

“LA Unified took a 10 percent pay cut,” Dowden said. “I mean excuse me. They took a 10 percent pay cut. Who does that to teachers? Well, this world today does that to teachers.”