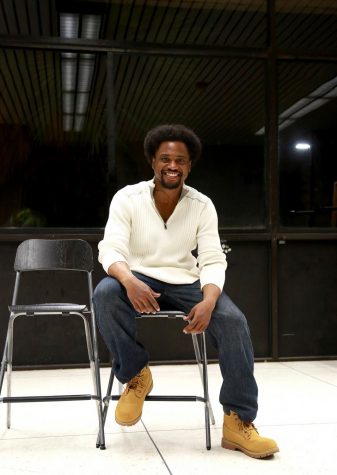

Homeless student pursues comedy career in LA

Warning: Explicit language

May 8, 2019

He spent his first night in town crouched on the floor up against the wall of a homeless mission shelter somewhere in downtown Los Angeles’ Skid Row.

For two days he sat there with headphones on, clutching his suitcase and a plastic bag filled with snacks, chips, juices and the few sandwiches his mother prepared for him to bring along the journey.

33-year-old El Camino College student Romeial “RISO” Hilaire left his home in the Uptown projects of New Orleans on June 4, 2018, to fulfill a lifelong dream of moving to LA to make a fresh start and reignite his passion for comedy.

“Comedy is a gift,” Hilaire said. “ And when you do comedy because you love it, the money is going to chase you because you’ll get up every day for a purpose that you love. So I can’t give up. It’s not in me.”

While inside the mission walls, he’d blast Big Sean’s “One Man Can Change The World” through his headphones to ignore the chaos going on all around him that night.

The sprawled out bodies of countless homeless men, women, and children seemed to fill every nook and cranny of the shelter. Spaced out crackheads accompanied by the smells of burning plastic and tweakers getting spun out on meth surrounded him.

Despite all of that, Hilaire took comfort in the fact that he’d made it to LA. And although his initial plans had not panned out, he’d find the silver lining in the clouds.

“They always say if you want to make God laugh, tell him your plans because he has plans for you,” Hilaire said. “You know, we tend to get upset when God shows us different, but what we miss out on is that his plans are bigger.”

His first days

Hilaire spent two days on an Amtrak before disembarking LA’s Union Station only to find that his hosts from the hospitality application, Couchsurfing, were no longer answering his phone calls or responding to his texts.

“I’m like what the f—-!,” Hilaire said. “I was trying to call them and let them know that I was getting closer, but when I finally got off the train I realized I was just screwed.”

He ordered an Uber and asked the driver to take him to the safest location in town where he might find a place to crash for the night until he could figure out what to do next.

“Are you homeless?” the driver asked.

He paused for a moment.

“I guess I am now,” Hilaire said.

For the next two days, he would find himself holed up inside the Skid Row’s mission walls.

“I’m not even from here man. When I tell you the first time I pulled up to that damn place, I thought it was an accident,” Hilaire said. “I said, ‘Hell No, man!,’ that Skid Row should be called Psycho Row!”

After two sleepless nights with his back against the wall, he decided it was time to move on. Without checking out, Hilaire recalled leaving the shelter after ordering a second Uber when something happened that he’d never forget.

Upon its arrival, Hilaire ran back inside the shelter to collect his suitcase but inadvertently left the bag of food he’d carried from New Orleans with him next to the vehicle on the sidewalk, when he noticed on his return, his food scattering away in different directions.

“It was like that movie ‘Coming to America,'” Hilaire said. ” [Homeless people] were walking around just eating all my food … it [felt] like, ‘I want to kill all you motherf——s right now, but all I want to do is get the hell out of here more than anything.”

For the following nine months, he would often sleep inside the lounge of the Harbor-UCLA Medical Center in West Carson until he was relegated to the Emergency Room (ER) by security guards in the hospital.

“Man, that was a freaking circus. I feel sorry for anybody who’s still sleeping in there today,” Hilaire said. “I bet I know all of their names.”

Months of living in the streets by day and sleeping in the ER by night ended when People Assisting The Homeless (PATH), an organization located within the Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, provided him with interim housing at the Salvation Army’s shelter in Bell, CA.

“We found that permanently housing people [reduced]… ER visits,” Veronica Turner, Homeless Task Force supervisor at the hospital, said. “The ER is not a hotel, so we try to get them into some kind of permanent housing outside the hospital.”

Home is where the heart is

Since his childhood in New Orleans, Hilaire, or “Riso”, as he is better known to folks back home, remembers having a sense of humor. He recalls laughing at things he only seemed to pick up on, making his parents wonder about their son.

“I guess it was voices I was hearing or something … I would always laugh to myself … and every time I would do that my dad or my parents would get upset,” Hilaire said. “And they would say, ‘Romeial, What the f—k is so funny?'”

After experiencing the devastating effects of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Hilaire recalled the sentiment going around at the time that every boy or young man would thereafter be considered men. And as such, they’d have to be ready to meet any challenges life threw at them head-on.

So in 2006, he’d set out to pursue his comedic talents and began to perform at Barataria Live in Marrero, Louisiana. There, he not only developed his comedy chops but also realized he had a special talent-the “gift of gab” for hosting other entertainers too.

“Never let anyone tell you ‘you’re too silly’,” Hilaire said. “God made you different. To be put in this world to bring love and laughter and joy to people’s lives through naturally being yourself without harming others or embarrassing others, that’s a gift.”

Yuri Anita Lavender Hilaire, Romeial Hilaire’s sister, was the first person to inspire in him the pursuit of comedy, he said. She would be a constant presence during his shows providing support.

“He would often perform in New Orleans, and in the Baton Rouge area,” Yuri Hilaire recalls. “I would be there to help collect the tickets and cash for the shows. I’ve been very proud of him.”

There were other places like Turnarounds in La Place, Louisiana where he continued to develop as a comedian and host. And Cheers in Baton Rouge, the last place he performed at, he said, before taking the leap towards LA.

“In New Orleans, I went from being a famous local comedian, but my name started falling off,” Hilaire said. “I was doing well as a local comedian working solo until I set up my show “What The Hell is So Funny?”

Hilaire said that he started to be known less as a comedian and more as a host during the Comedy Central type show that he created where he’d introduce different comedians at Barataria Live in Marrero Louisiana.

But after some time he said, was beginning to feel like things weren’t progressing further and was starting to question his place and his future in New Orleans.

“I felt trapped in the midst of it,” Hilaire said. “When you’re in a mental jail, you have to find a way to escape. I was working hard for years and looking out for people, but when I looked around I had little to show for. So, I decided to start over.”

He mentioned a proud moment during one of his shows in 2016 was when he opened up for an established comedian like Eddie Griffin at the Harrahs’ Casino in New Orleans, to whom he was able to provide copies of his recorded DVD “Meet Riso The Hero.”

Starting over

For now, Hilaire said he is happy to have made it to LA and is ready more than ever to put the time and effort necessary to succeed on both the academic and comedy stage. But, he acknowledges that there will be other challenges ahead.

During Spring Break this semester, he went back to Louisiana to visit his sister and mother for a few days, only to learn upon his return that he’d lost the room he had been provided at the Bell Shelter.

“Right now I just need to get housing. I need to get my housing,” Hilaire said. “where I can just lay down, and get things together, get my thoughts straight. Second, I’d like to start looking for gigs in entertainment, because I’m too old to be doing what I don’t want to do.”

He is struggling right now Hilaire said but sees his current situation as temporary and would rather focus on his bigger purpose:

“I’m never going to be happy if I’m not making a full time living doing what I love,” He added. ” And it’s not for the money. You know it’s not just for me. It’s for my community…I don’t want to just inspire blacks, I want to inspire whites, Hispanics, Asians, Indians, the whole world.”

Sharonda Barksdale, a financial aid advisor and foster youth and homeless liaison for EC said for older students like Hilaire who are on the verge of homelessness or for those currently facing homelessness, the chances of being housed have become “slim to none.”

“A lot of housing right now is tailored towards youth ages 16-25,” Barksdale said. “It’s super difficult right now to help [older students]. Just even in talking to some of the other agencies, … there’s really not a lot of options.”

Hilaire said a simple clerical error cost him his housing, however, due to his good standing at the shelter, he may be placed back in the same facility that aided him the first time around at the Harbor-UCLA Medical Center,

“You know when you’re homeless and you’re out here sleeping in the streets, you really start to think ‘I f—-d up,’ or, ‘God has really forgotten about me,” Hilaire said. “There’s a lot of doubts. But having the consistency and the passion to keep going, that is untouchable.”

But Hilaire reflected on his current situation and thought back to the time in New Orleans when he was gaining popularity and recognition for his stand-up comedy shows as a performer and host. He had a car, he had a home and a girlfriend. But he said he would not trade today or yesterday to get it all back.

“I feel so free, I feel so rich and so wealthy than I ever felt living in New Orleans,” Hilaire said. “I’m always going to find myself back going to comedy no matter what I do, so that’s why I’m going to follow my dreams.”

Update: 12:18 p.m. Wednesday, May 22, visual adjustments we made for clarity.

Update: 1:40 p.m. Thursday, May 9, grammatical errors were adjusted for clarity.

Update: 3:10 p.m. Monday, June 3, an accompanying multimedia package was added to this story.